Carolyn Sealfon, PhD, teacher at University of Toronto Department of Physics and researcher at the Ronin Institute

csealfon@physics.utoronto.ca

Nancy Watt, President, Nancy Watt Communications

nancy@nancywattcomm.com

We would all like to build classroom communities where our students flourish. We would like our students to develop their curiosity, creativity, critical thinking, persistence and resourcefulness. As science educators, what can we learn from the arts?

In improvisational theatre (“improv”), an “ensemble” is a group of people that work together cohesively and support each other to co-create a performance, recognizing and building upon each other’s individuality and contributions. For social learners, participation in an ensemble can foster our best learning. Can we create ensembles in our classrooms?

Parallels of Improv to Scientific Inquiry: from Stage to Classroom

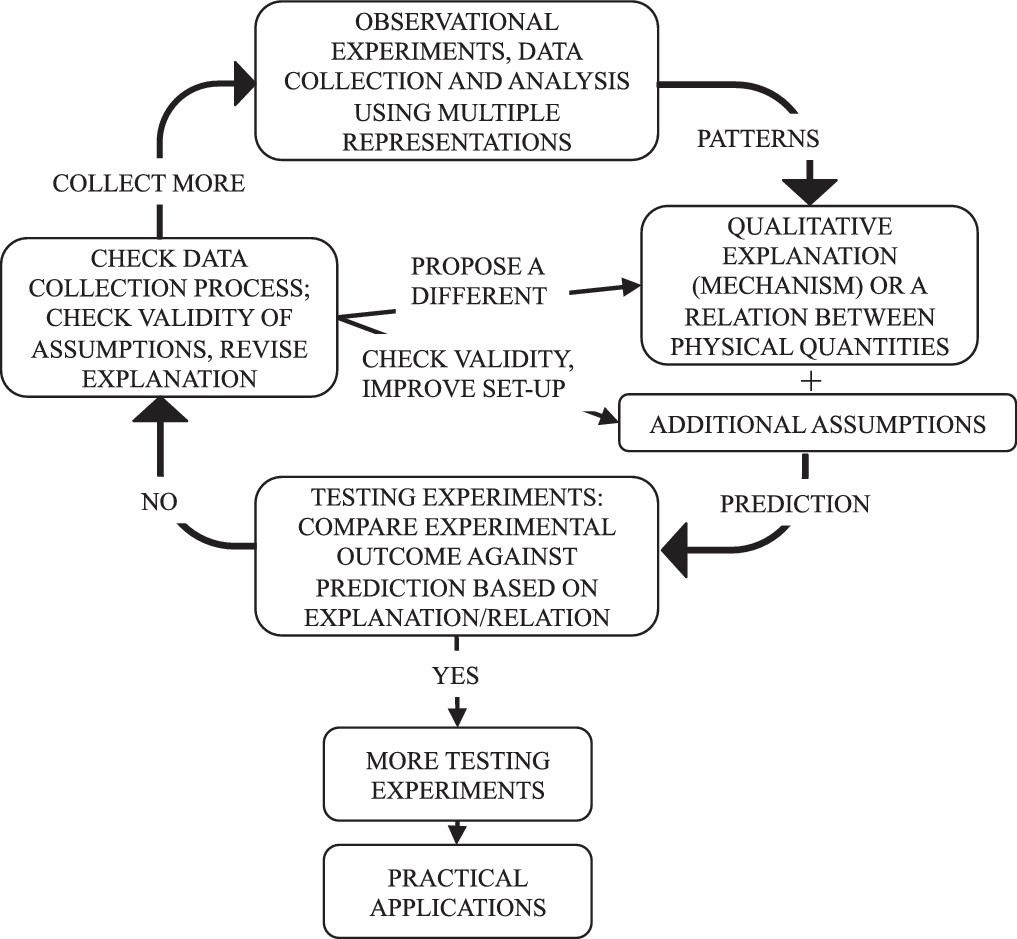

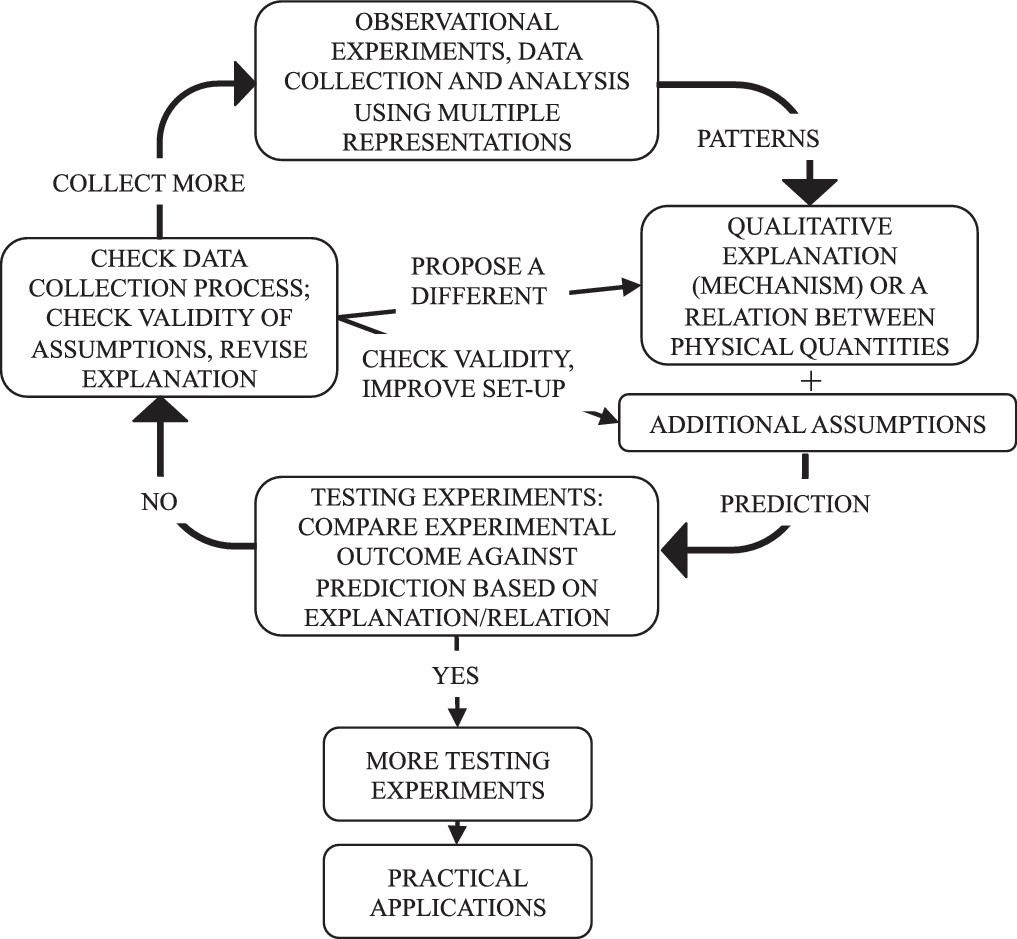

The joy and power of scientific inquiry relies on creative exploration beyond what is familiar into the unfamiliar and strange. One way to integrate this delightful inquiry into physics courses has been developed and refined by Eugenia Etkina and collaborators through physics education research over the past 20 years. The approach, called the

Investigative Science Learning Environment (

ISLE), empowers students to participate in the creativity and joy of scientific discovery while learning introductory physics concepts. A key step in the

ISLE learning cycle involves freely proposing creative possible explanations for observed phenomena without worrying that any idea might be too absurd. To maximize these teachable moments, we must listen carefully to students’ creative ideas without jumping to conclusions or imposing our models on them. Improvisational theatre offers a laboratory to develop listening skills and responsiveness to creative ideas.

ISLE cycle diagram. Reproduced from [1], with the permission of the American Association of Physics Teachers.

ISLE cycle diagram. Reproduced from [1], with the permission of the American Association of Physics Teachers.

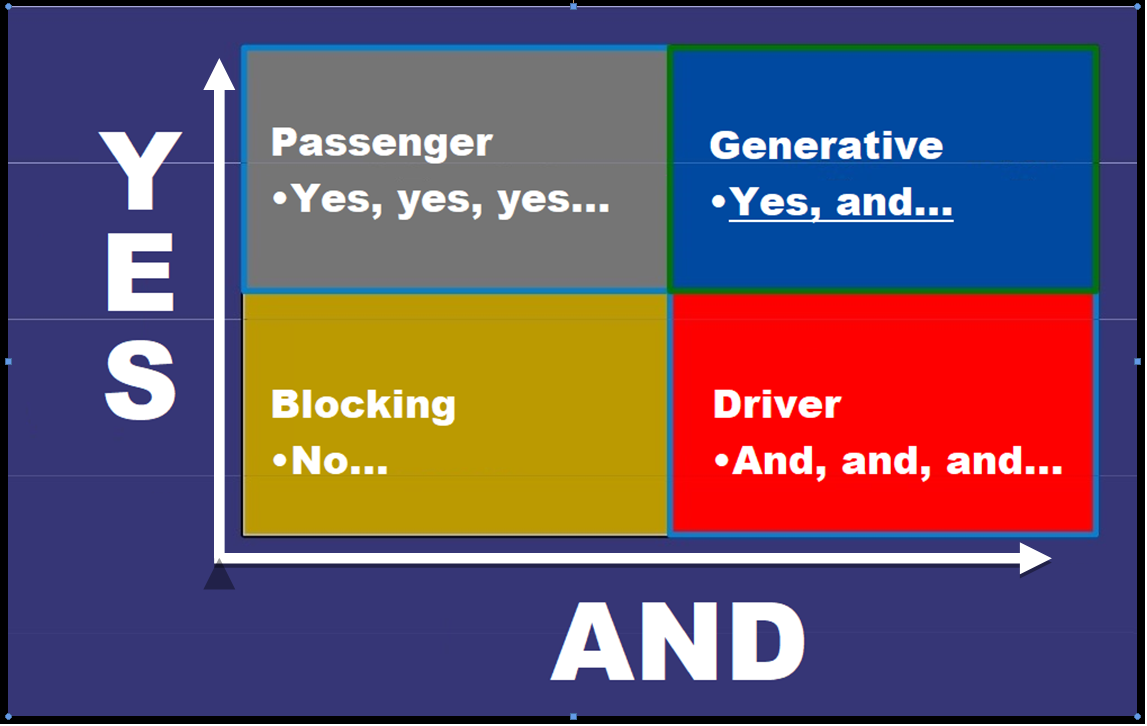

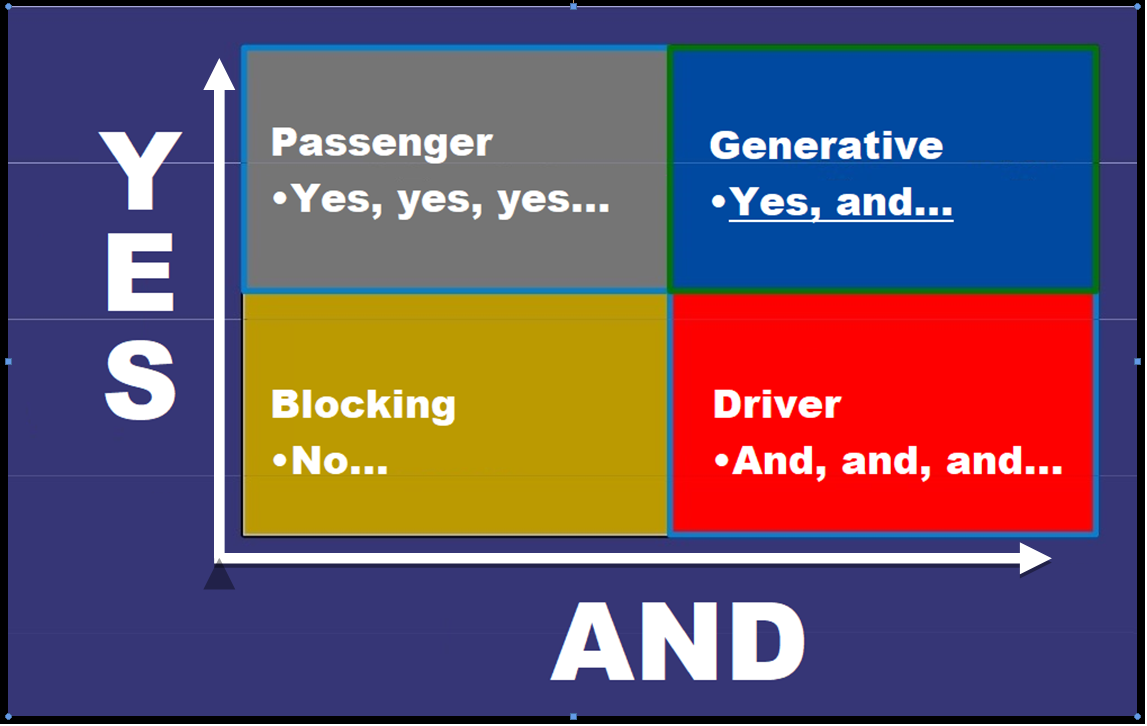

The fundamental principle of improvisational theatre is “Yes, and…”

By responding to an idea with

“Yes”, we are listening and acknowledging what the person is saying or doing as something valid to say or do. To respond with

“Yes” in improv does not necessarily imply that we agree, but rather that we genuinely hear and see the other. On stage,

we accept the reality that has been created. In the lab, we accept the reality of what we observe or measure. In the classroom, we accept the reality of what our students are thinking or suggesting. A “No” blocks the scene and shuts down co-creation with another. It implies denying, diminishing, or negating what someone else has said or done.

Saying

“and…” is our own contribution to the scene, adding on to what is happening. True collaboration or co-creation requires both the

“Yes” and the

“and…”. People who build without listening to others (“and…” without “Yes”) are called drivers in improv (“and, and, and…”), similar to traditional teacher-centered instruction in the classroom that does not invite the active participation of students. People who listen and offer affirmation without meaningful contributions (“Yes” without “and…”) are called passengers in improv.

This is summarized in the four quadrants below:

Diagram ©ISKME. Used under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license.

Diagram ©ISKME. Used under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license.

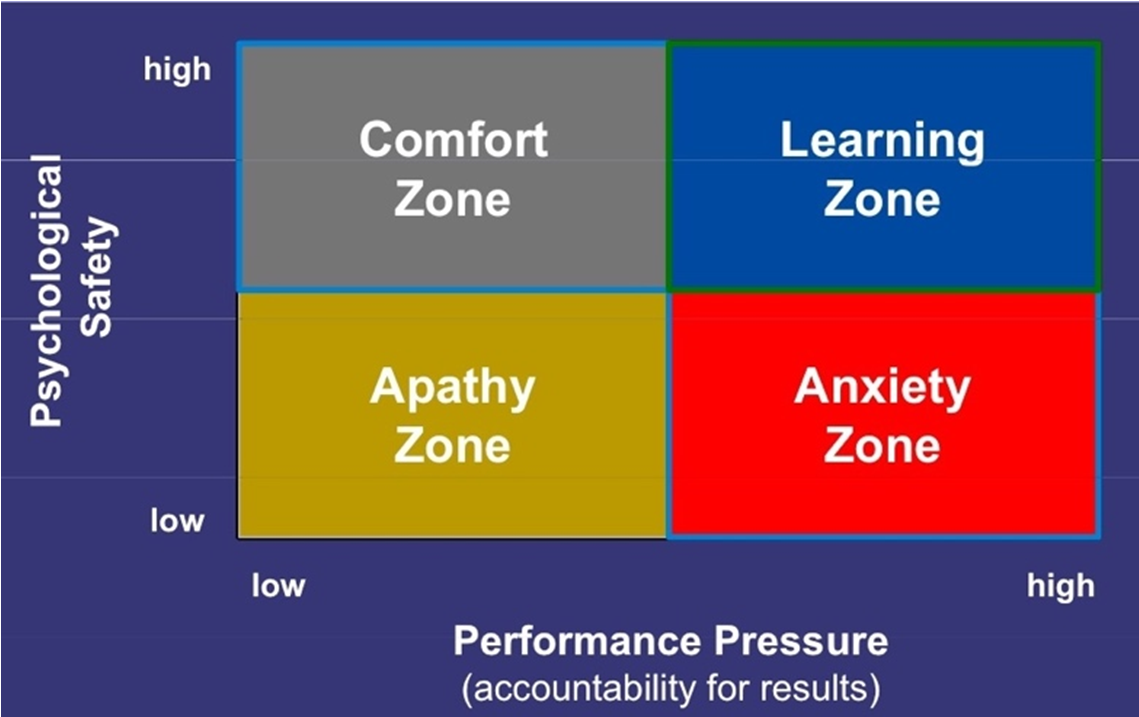

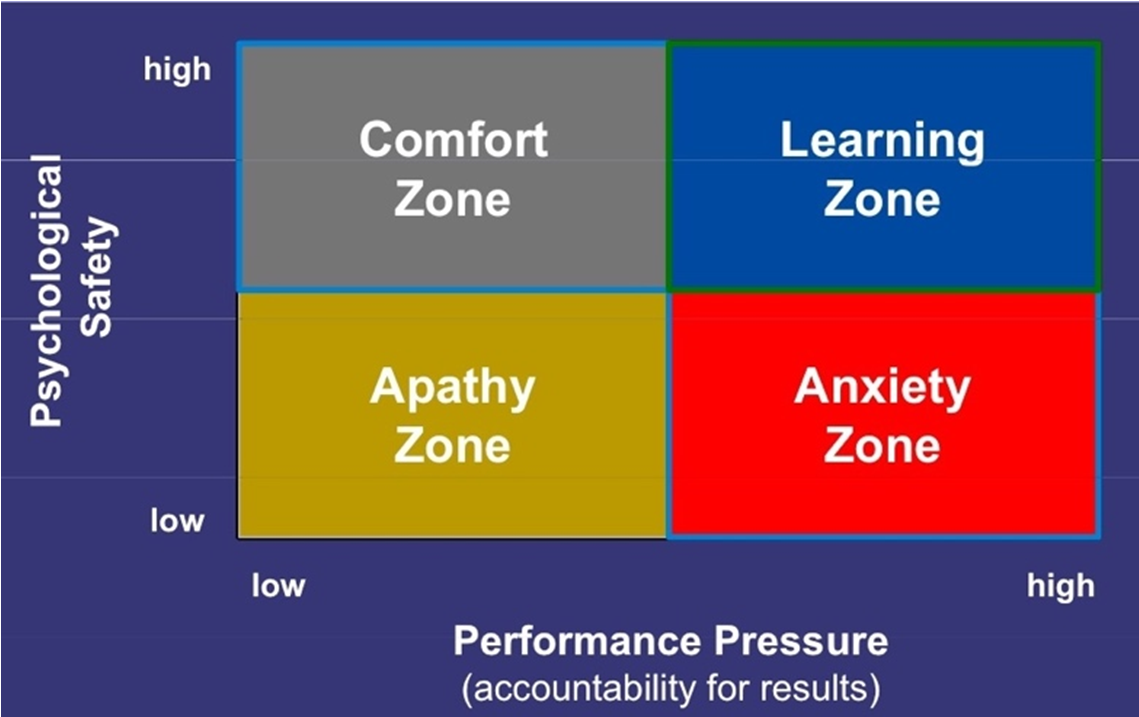

These quadrants map nicely onto quadrants that come from Amy Edmondson’s work on psychological safety:

©Amy Edmondson. Used with permission.

©Amy Edmondson. Used with permission.

To take the risks that will help us learn and grow, we must feel psychological safety. Fear that leads to a stress response inhibits both teaching and learning. There are so many little fears that we and our students grapple with: fear of failure, fear of making a mistake, fear of disapproval, fear of the unknown. Many students struggle with physics and math anxiety. Improv-inspired activities can help build ensembles and foster psychological safety.

The Roots of Improv in Education

Viola Spolin was an educator and social worker in Chicago who worked with immigrant children, many of whom were having difficulty with language, acculturation and learning. Together with another woman, activist and social worker Neva Boyd, they made up creative theatre games that transcended the age, gender, and ethnicity of the participants. The improv exercises resonated deeply both in spite of

and because of the creative (and often nonverbal) nature. (Later, inspired by her work, her son created the renowned improvisational comedy school

Second City.)

Spolin believed that improvisation proved to be a way out of the “approval/disapproval system” that blocks an authentic experience of ourselves and each other. She wrote that it was a path that frees us from the confines of our own evaluative, self-conscious and repetitive stories. As educators, we recognize this evaluative, self-conscious state in our students.

Improvisation opens us to our own aliveness, even in the smallest moments, through the process of spontaneity and unique co-creation with another. As Viola Spolin said, “We break down the walls that keep us from the unknown, ourselves and each other.”

Join us to explore these ideas and more in a fabulous community called

CESTEMER: Cultivating Ensembles in STEM Education and Research.

References

- Etkina, E. (2015). Millikan award lecture: Students of physics—Listeners, observers, or collaborative participants in physics scientific practices? American Journal of Physics, 83(8), 669-679.

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350-383.

- McKnight, K. S., & Scruggs, M. (2008). The Second City guide to improv in the classroom: Using improvisation to teach skills and boost learning. John Wiley & Sons.

Editor’s Note: This material was presented at the 2019 OAPT conference.

Tags: Pedagogy, STEAM