Chris Meyer, York Mills C.I., Toronto District School Board

Chris_meyer1@sympatico.ca

Pride comes before the freefall

What topic could be easier, right? It’s just straight up and down — no funny business. Freefall is the poster child of constant acceleration, everyone’s go-to example. We can teach this in our sleep! But we might not realize that we are setting up our students for a physics ambush. While our students’ first freefall problem might seem straightforward and understandable, the second one often contains a trap!

Second freefall problem: “You drop a ball from a window 1.9 m above the ground. How much time does it take to hit the ground?” The student sizes up the problem; it seems easy. The displacement is 1.9 m downward. The acceleration is known; the student is feeling confident. They can find the time if they know one more motion quantity. Ah, the final velocity is zero! Problem solved!

And thus, the unsuspecting student is ensnared in the most common trap of freefall motion. This highlights the real challenge of understanding freefall: students need a genuinely sophisticated understanding of forces to make use of freefall ideas. Emphasizing freefall before studying forces allows students to tumble into numerous, all-too-common learning traps. Let’s nimbly dodge these traps and explore a better way to study freefall!

The pitfalls of learning freefall

Before I understood the pitfalls of freefall, I constantly reminded my students that they cannot use a final velocity of zero when an object hits the ground! I would say this over and over again and they would return the favour by making this mistake over and over again. I was confounded. They firmly seemed to believe that the final velocity was zero since the object was at rest on the ground after its fateful fall. Funny that. Our problem as teachers is that we can’t make them “believe the right thing” by telling them; they need a detailed exploration of forces. This starts with a solid grasp of the first law of motion and its corollaries: how the state of motion changes when the state of force changes (what I call the force-change principle); and how it takes time to change the velocity of an object (what I call the inertia principle). Without these concepts, students cannot make the crucial decision of freefall: when does the interval of freefall begin and end?

The alpha and omega of freefall

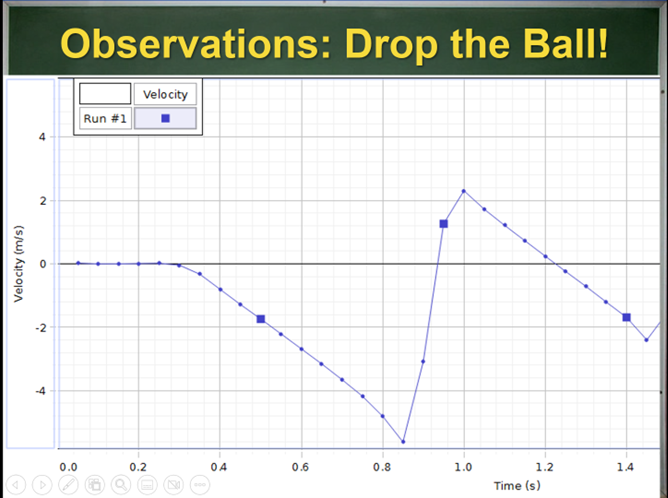

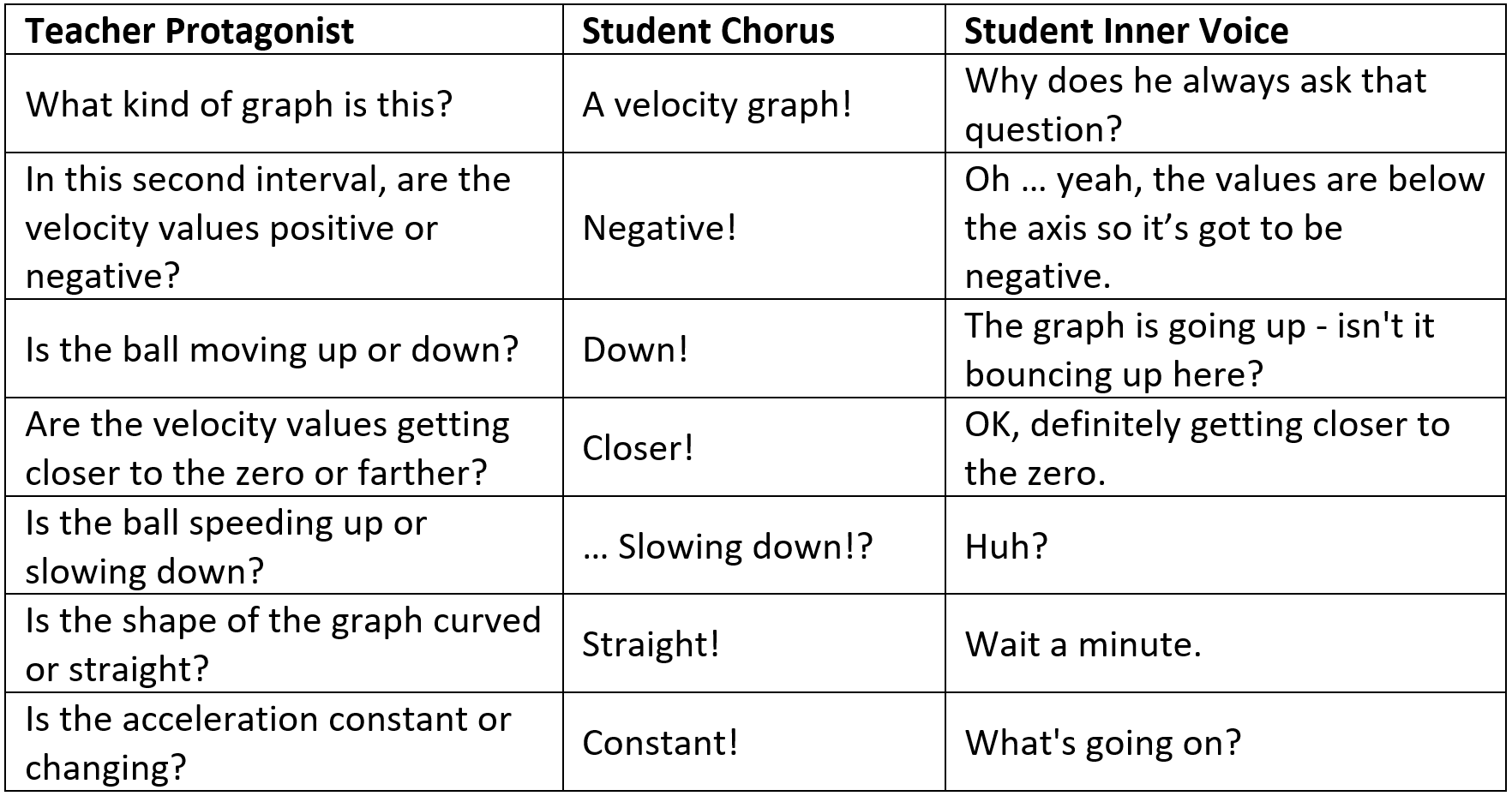

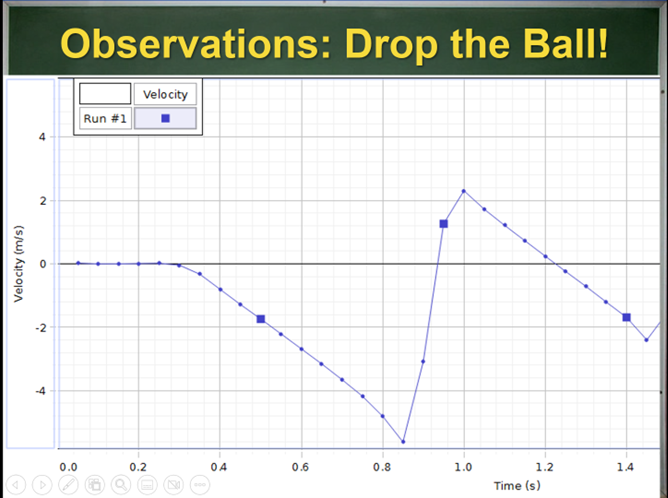

Identifying the beginning and end of freefall is tough. Just ask a student about the speed of a falling ball the moment it is “caught” in a hand; most will say, “zero.” Toss a ball up and let it fall down. Then ask students when the interval of freefall began and ended… and then stand back! Yikes! Most will say, “it started freefall at its highest point and ended when it hit the ground.” If these students successfully solve a freefall problem, it is likely due to luck or rote habits rather than a reliable understanding. To teach students how to determine when freefall begins and ends requires a real investment of time and thinking energy. I begin by dropping a deflated basketball and collecting some data:

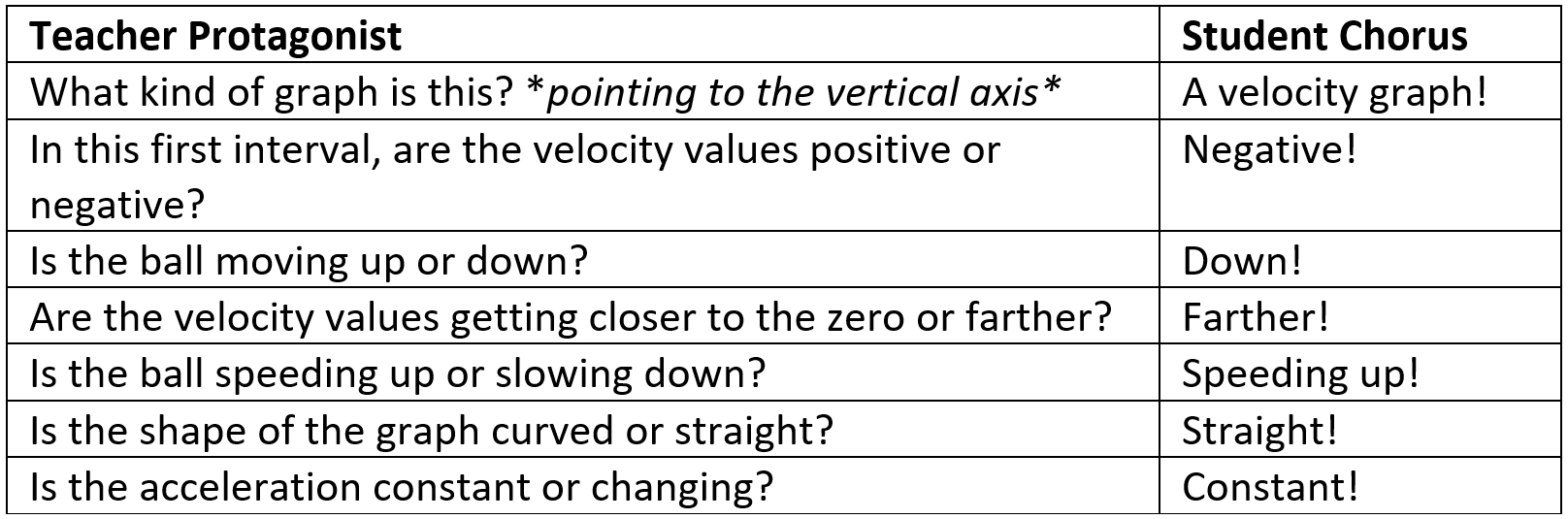

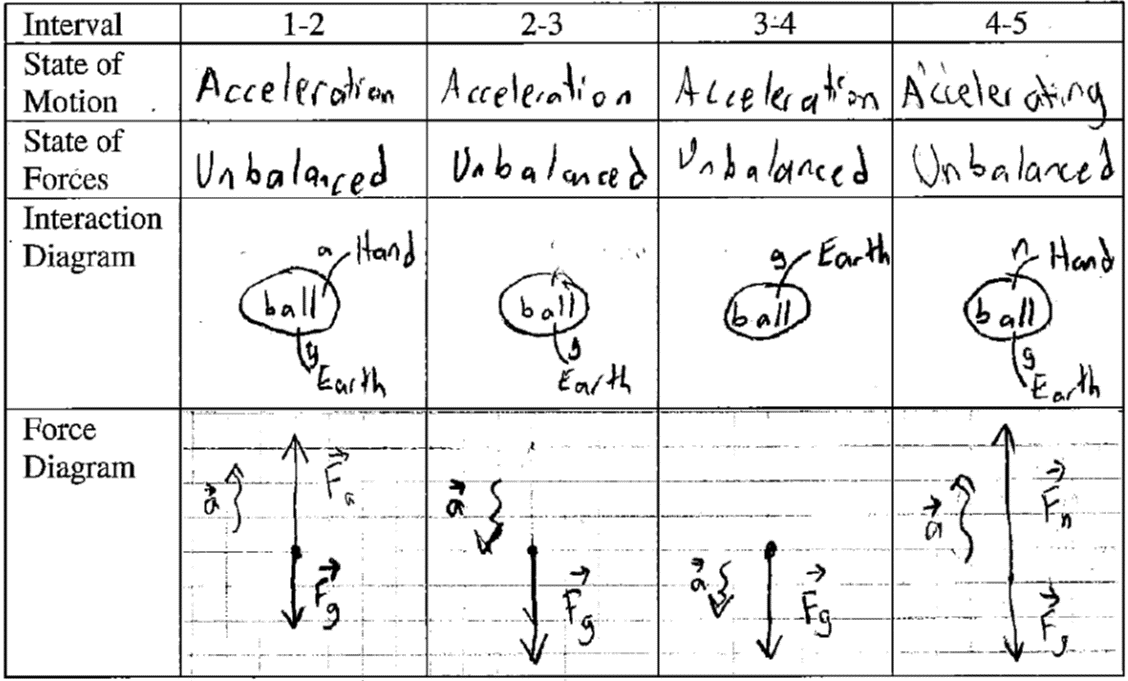

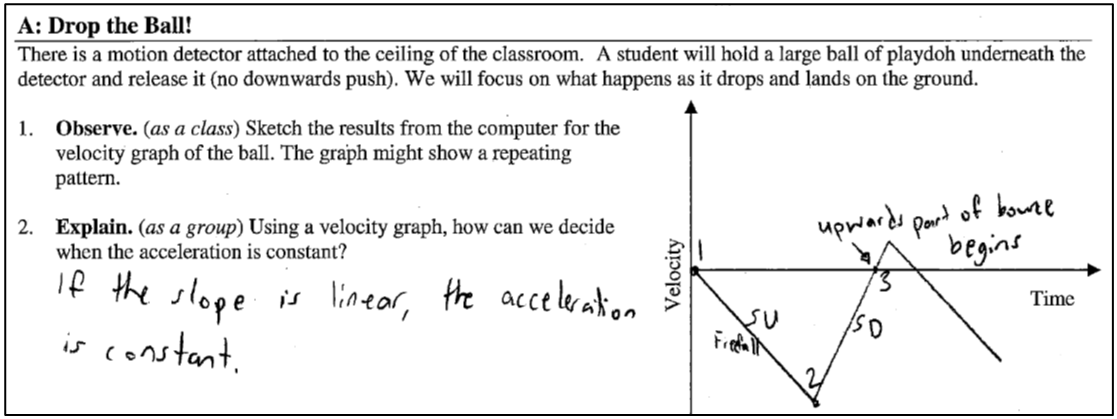

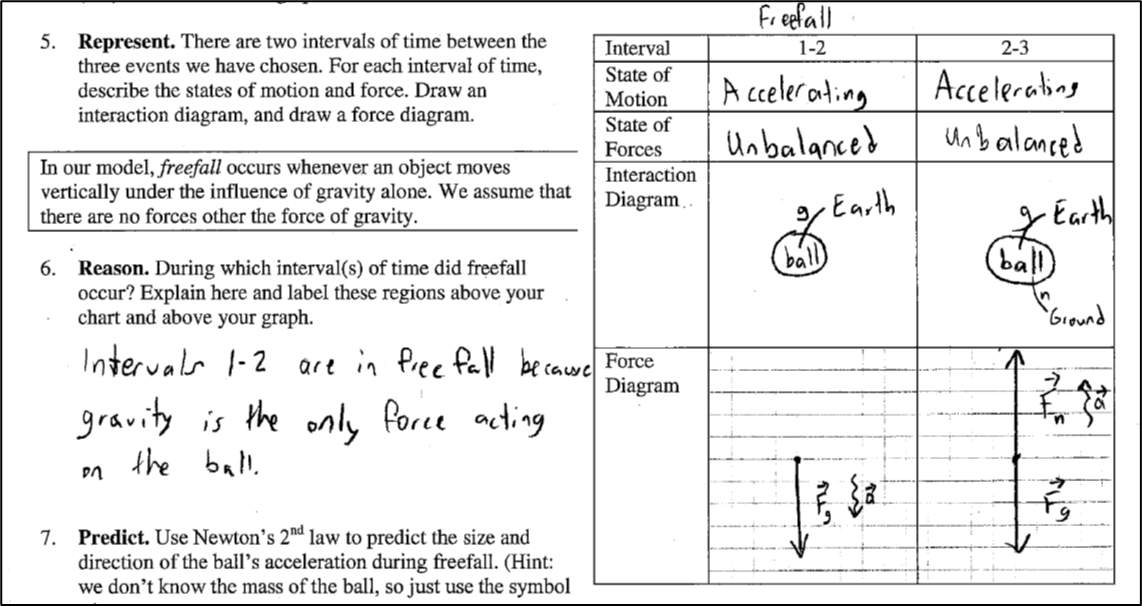

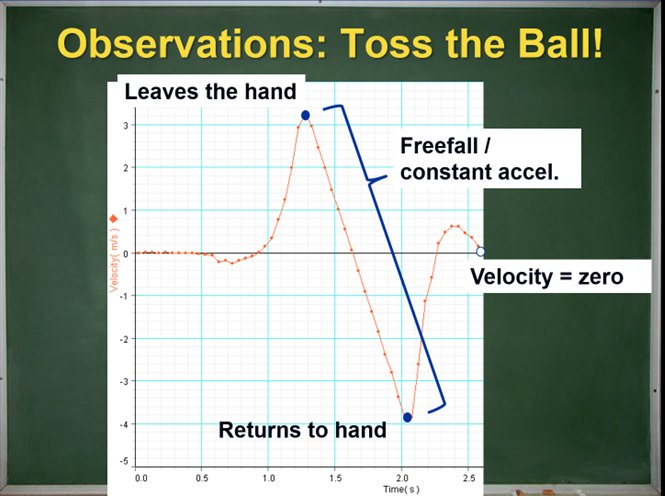

We use a motion sensor to collect velocity data for this situation. Interpreting a velocity graph like this is quite tough! In our motion unit, we drilled a thinking process that goes something like this:

Graph interpretation process: The teacher poses questions to the class and students respond together out loud.

And so we agree in the first interval the ball is falling downwards and dub this “freefall”. Then we look at the next, more challenging interval. I align my meter stick to the projection on the screen to match the data for the second interval, going from its lowest point until the zero velocity.

The second interval is genuinely perplexing: the ball is moving downward but slowing down! How is this possible? Here we discuss the deformation of the basketball as it moves downwards and slows. In our first lesson on forces, we used an object’s

change of shape as evidence for the existence of a new interaction, in this case an interaction with the floor. So, we conclude that the ball has contacted the ground and is slowing.

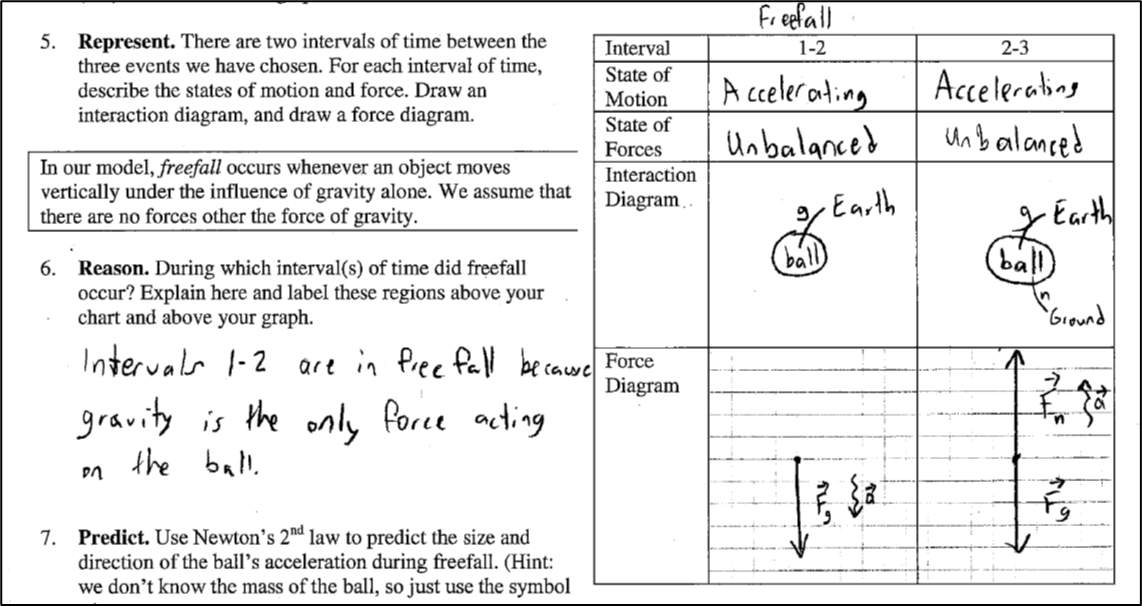

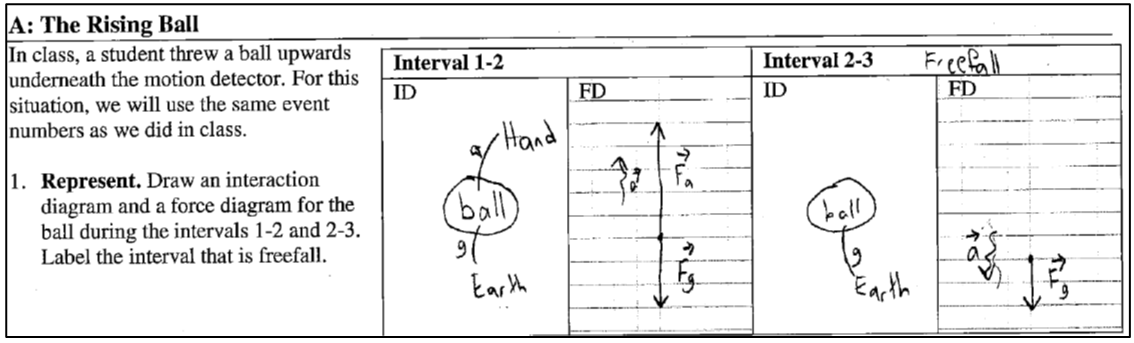

At last, we are able to identify three events: (1) the ball is released, (2) the ball contacts the ground, and (3) the velocity is zero. Here is a student's work:

And at last, we can for the first time define the beginning and end of the freefall interval! Next, we use our tools to represent interactions and forces, making our understanding of the two intervals clear. Freefall happens in the first interval only, before the ball contacts the ground. Notice that we take time to analyze the interactions of the second interval when the ball is contacting the ground. This is important for reinforcing an understanding of when the freefall interval ends.

Events and intervals, moments and processes

Events and intervals, moments and processes

Students need a few crucial tools to follow this analysis of the falling ball. The first and most important tool is an understanding of events and intervals. These ideas are developed in our earliest lessons on motion and are used everywhere in our physics courses. It's hard to believe I taught physics for so many years without consistently and explicitly using these two concepts! Their value is immense, serving as both a magnifying glass and a bright light, allowing us to perceive more clearly what has always been happening around us.

- Event: something that happens at a particular moment in time and position in space.

- Interval: the duration between two events, with our focus being on time only (special relativity greatly extends this “simple” idea!).

Events allow us to talk precisely about when things happen and serve as markers in the temporal flow to define intervals of interest. Making the distinction between an event and an interval is critical to understanding physics. Many physical processes, especially ones that happen in little time, are often perceived as events when in fact they are intervals: two cars colliding, a bat hitting a baseball, the catching of a ball, a heavy box suddenly stopping. It is no wonder students have difficulties deciding what velocity values to use when two distinct events defining an interval, in their minds, collapse into one event: the collision, the hit, the catch, the stop. This misperception is regularly reinforced by how we talk about physics in our classes, so a judicious use of language is needed. Take careful note of the language used throughout this article: I'm doing my best to write real good!

The first law’s passengers: corollaries

There are few physics ideas that delight and surprise more than the first law of motion. This “simple” law is the clown-car of physics: novel ideas, one after the other, just keep popping out of it! And so, stumbling forth wearing wacky shoes, disgorged from their vehicle, are what I call “the corollaries of the first law”. All these corollaries derive directly from the first law, so hopefully you will think, “well yes of course, this is not surprising,” but you are not my target audience! Well, sort of but not exactly. These ideas are indeed surprising to students and take years of work to unpack or stumble upon. Let's try to reduce the stumbling by deliberately introducing them to students with clear labels.

Corollary: the force-change principle

What I call “the force-change principle” is the idea that when a force changes, the acceleration changes simultaneously. Obvious, right? But it's not. Students commonly suggest that a force, or the effects of a force, can continue after the interaction has ended. Ask students to draw a force diagram for a ball thrown upwards, many will draw an upwards force vector long after the object has left contact with the hand (when probed about it, they may call this “the force of the throw”). This corollary trains students to focus on moments when an interaction begins or ends and to look for the changing force and acceleration.

Corollary: the inertia principle

I don't use the word “inertia” in my formal definition of the first law because it interferes with a lot of good force thinking. Students, taken in by the allure of inertia, say curious things like, “the object keeps moving because of inertia”. This is confusing: the only useful “explanation” for a state of constant velocity is that the net force experienced by the system is zero. In Newtonian physics, this is an empirical fact of our universe that we don't explain: constant velocity is correlated by exhaustive observation with a net force of zero. But the idea of inertia does explain something about our universe, so what could that be? My proposal is this: the inertia principle tells us that it always takes time to change the velocity of an object. There are no instantaneous changes of velocity no matter how sudden a change might seem; an interval of time is required and a physical process is in effect. This is another tool that helps reduce the confusion about intervals and events. Did the velocity change? Sure did, now the ball’s just sitting there on the ground. So, there must have been an interval of time while the object was slowing down. Often the interval is so short that we don't notice it. The inertia principle helps us notice.

Everything is freefalling into place

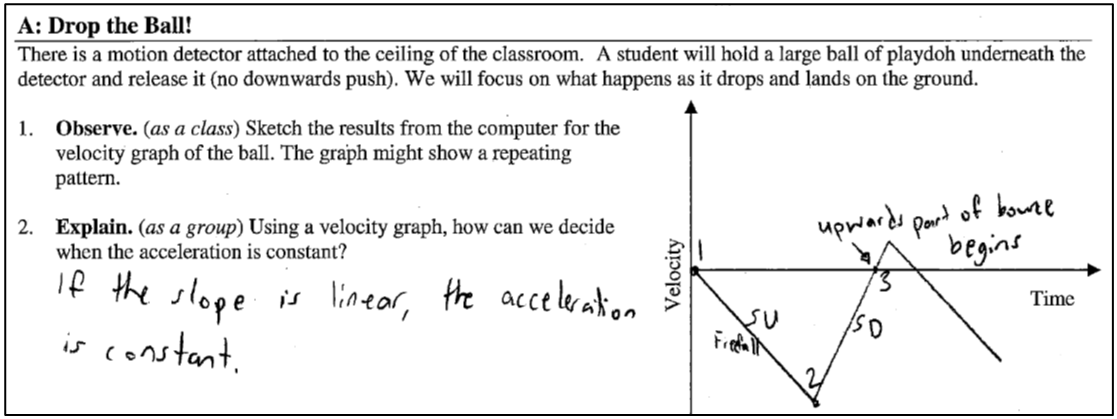

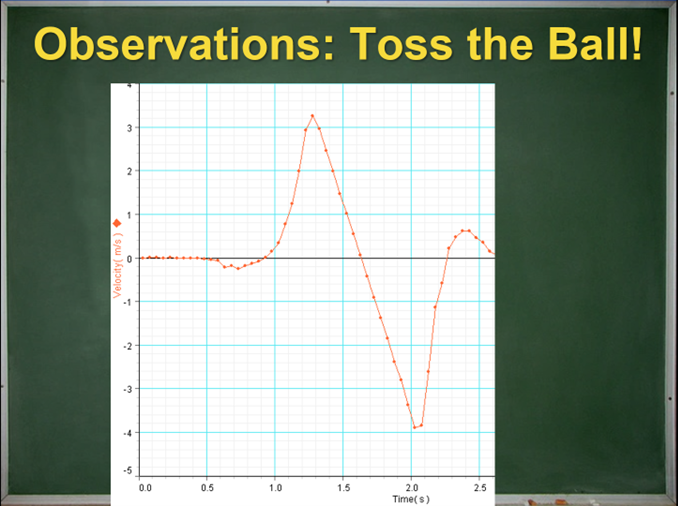

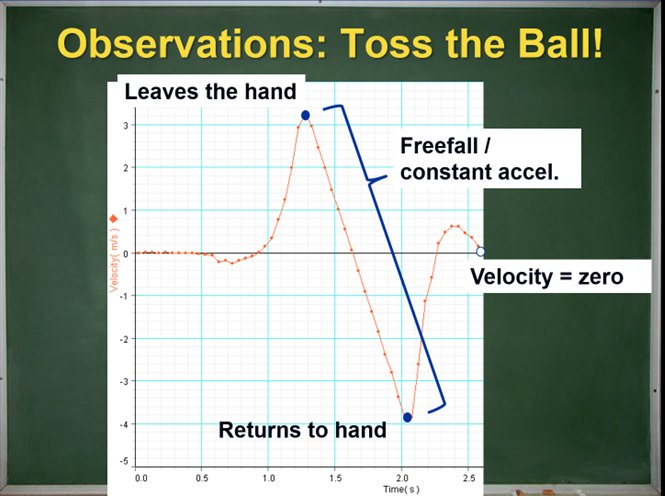

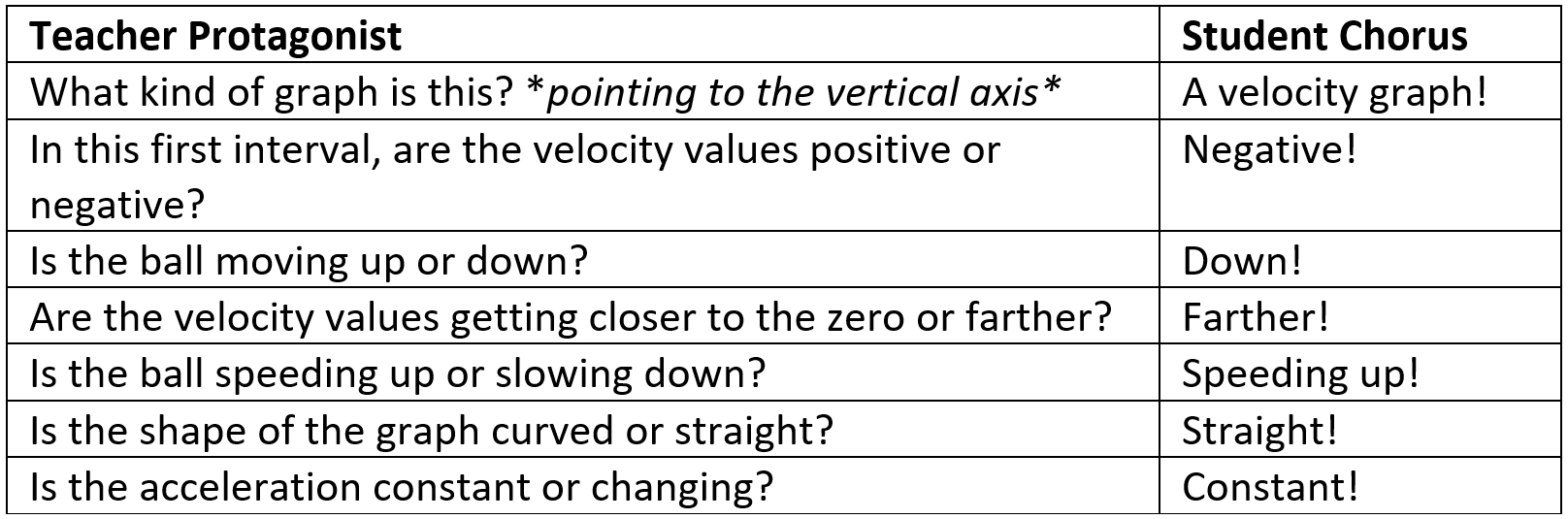

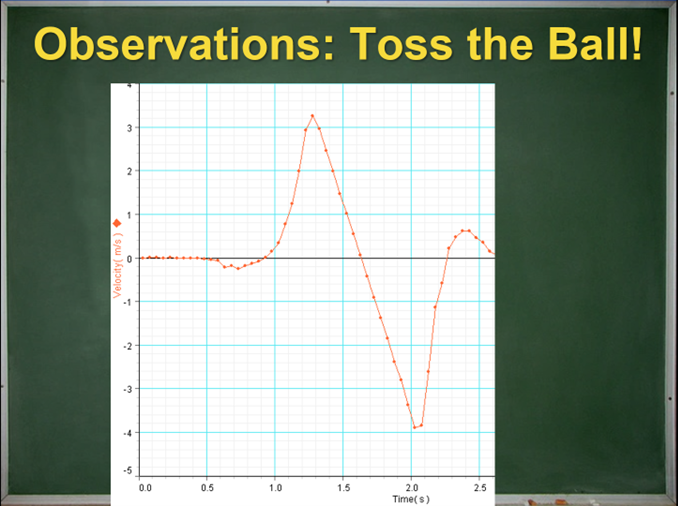

We have made serious progress with the falling ball, so now it's time to put our understanding to the test. The second scenario that my students explore is the full up-and-down toss of a ball, including throwing and catching. We use the motion sensor to collect data like this:

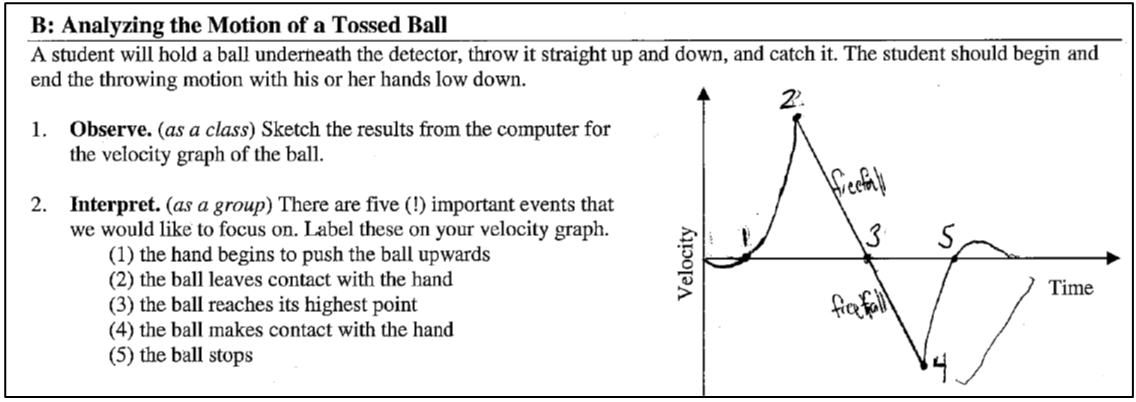

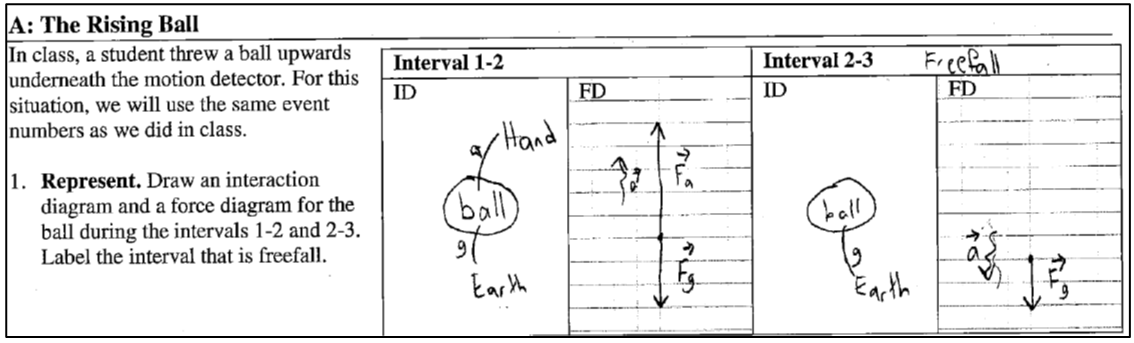

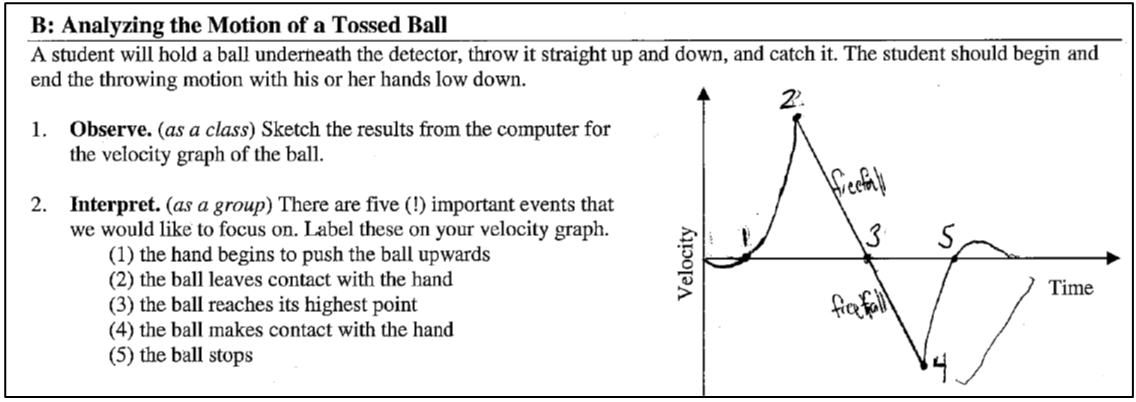

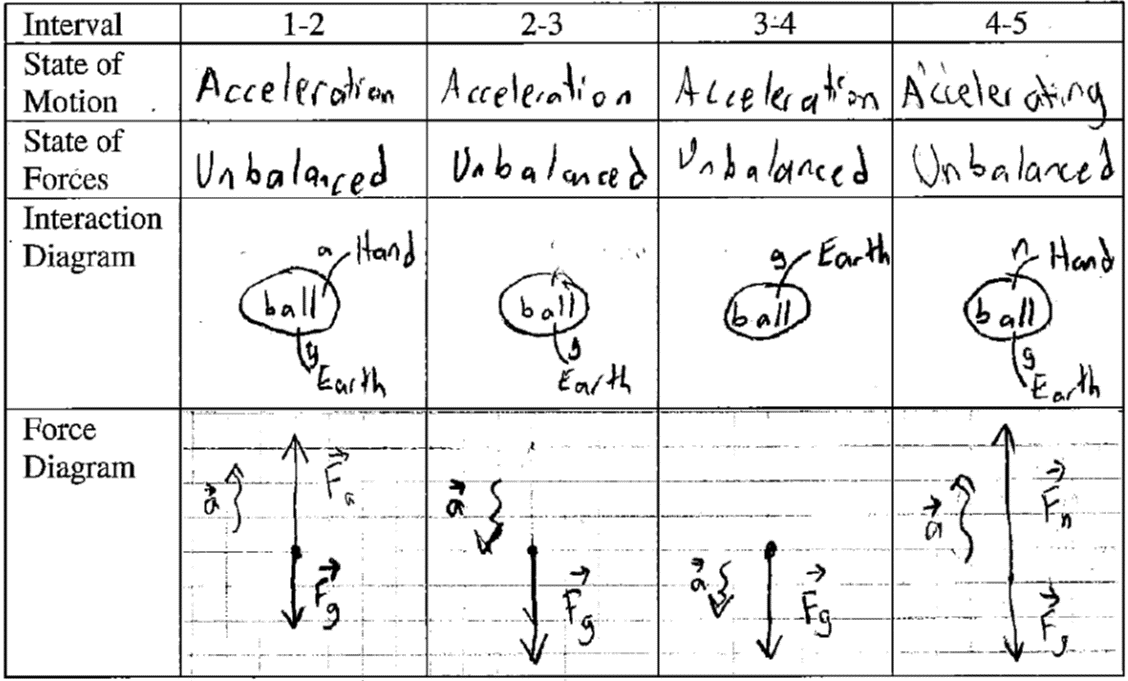

This velocity graph requires a lot of careful unpacking. Luckily, we have warmed up with the previous example! I lead the class through our call-and-response process until we decide where to label five events: (1) the hand begins moving the ball up, (2) the ball leaves contact with the hand, (3) the ball reaches the highest point, (4) the ball contacts the hand, and (5) the hand brings the ball to a stop. Note the small confounding interval of negative velocity as the hand is “winding up” and preparing to throw! The real world is complex, but the careful interpretation of the graph allows us to define our intervals of interest and focus our attention on the right place. Here is a student’s work:

We spend some time determining which point represents the highest position in its journey. On a position graph, finding this point is a slam dunk. On a velocity graph, without careful interpretation most students will choose the location of event 2 as the highest point. There are a few reasons why this graph is challenging to interpret correctly. Velocity graphs are not as intuitive to read as position graphs. There is also the challenge of understanding when freefall begins and ends: most students want freefall to begin when the ball reaches its highest point. After all, the term freefall suggests motion downwards! However, the graph clearly shows an interval of constant acceleration from event 2 until event 4.

Even this doesn't make sense unless students carefully interpret the graph and understand that interval 2-3 represents movement upwards that is slowing and interval 3-4 represents movement downwards that is speeding up. Another challenge is an observational impression that the ball is at rest at its highest point for a short interval of time. Since it is moving slowly both before and after that moment, it can appear to be “at rest” near the top of its trip. What do you think?

Perhaps this impression is one reason students will often say that the force of gravity at the highest point is zero. Only by the scrupulous interpretation of the velocity graph do we see that the velocity of the ball at the highest point is zero only for an instant in time and that the acceleration (and therefore the net force) is never zero. Again, confidence with events and intervals is critical. To untangle all this, we must analyze the interactions carefully.

We see from the force diagrams that interval 2-3 and interval 3-4 show identical interactions and forces. Because of this we can confirm that our definition of freefall extends to movement upwards, depending only on the forces acting on the system. So during interval 2-3, the ball was “freefalling up”! But don’t use that phrase! This analysis also encourages students to reconcile a common faulty explanation: many students say that the ball experiences the upwards force of the hand throughout its full upwards journey and possibly that at its highest point the force of the hand stops and the force of gravity “turns on” or becomes stronger. Never heard this? Listen to more students! You might just be able to see in the work above for interval 2-3 that this student originally drew an upwards force vector that was larger in size than the force of gravity (it’s going up!). A super good set of force diagrams for this scenario would show all four force of gravity vectors the same length.

Exploring the rate of freefall

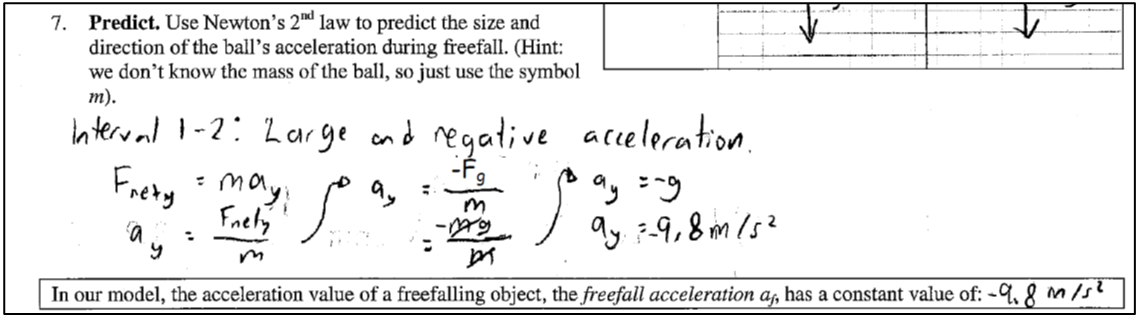

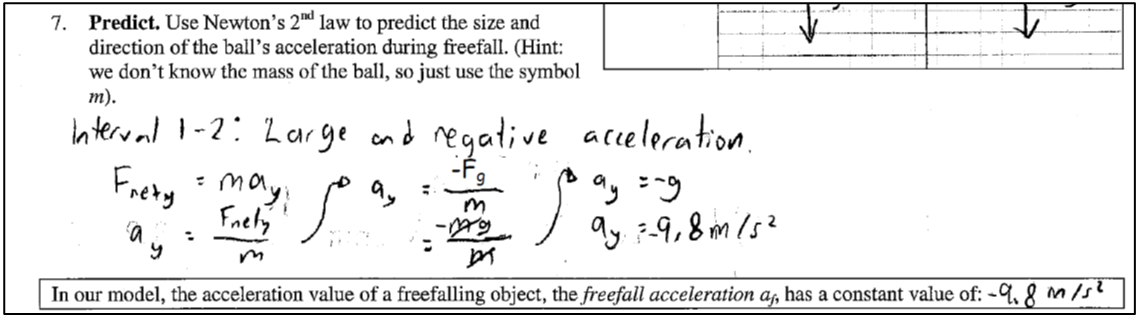

Our ability to make predictions is what makes science interesting and powerful. Based on our analysis of these velocity graphs, we can construct a scientific model to describe freefall. Models usually start simple and become more complex and reliable as we refine them (we just added upward movement to our freefall model). Here is our first empirical prediction using our simple model of freefall.

Quite conveniently, we already have the data to test this prediction! All we do is find the slope of the velocity graph during the freefall interval. And sure enough, we discover that it does not agree with our prediction! Well, it is usually close, often around 9.6 or 9.7 m/s

2. Good enough? Not at all! This points out that there is more for us to learn: perhaps our model needs some assumptions or conditions for giving reliable results. What is affecting the acceleration of our falling object? In our next lesson, students make empirical tests of freefall to answer this question, but discussing that lesson is for another article — we have enough to chew on here!

Don’t let language freefall off your radar

The likelihood of students falling into a physics trap is increased by the common, unclear use of language to describe freefall. Let's take a tour of the linguistic challenges our students face. And for the record, the following examples of the poor use of language are all ones I have said to my students!

- Freefall. Ask someone the direction in which a freefalling object moves and you are likely to get only one answer: down! In science, we blithely extend ideas beyond their original use or beyond the day-to-day interpretation of a word. An interval of freefall can include movement both up and down. You can even toss a ball straight up and catch it before it reaches its highest point so it never moves downward at all. Ask a physics teacher, “was that freefall?” and they will say “well, it's a little bit unusual, but yes, for sure!” However, this is quite counterintuitive to students and is one reason why students prefer to believe that freefall begins at the highest point. Later, we go hog-wild and extend the idea of freefall to cover projectile motion, orbital motion, and any kind of gravitational central force motion (and then the idea is turned inside-out in general relativity… thanks). The label “freefall” can cover a lot of physics!

- At rest. Ask a person to picture an object that is “at rest” and they will think of an object sitting there on the ground minding its own business … or themselves in bed. Because of this powerful association, we should only use the term “at rest” to describe an interval of zero velocity and never a moment with an instantaneous velocity of zero (however, if students aren't familiar with events and intervals this distinction will not makes sense). During freefall, an object is never at rest, even at its highest point! Remember, some people have a visual impression of an object spending a bit of time at its highest point. Don't reinforce that by using the term “at rest” as its description (or worse: “at rest for a moment” or “instant”).

- Constant acceleration. Keep terminology as simple and clear as possible. “Uniform acceleration” is less clear. Keep the uniforms for the bowling alley.

- Freefall acceleration (af). This is preferable to “the acceleration due to gravity” (ag) which is too close to “gravitational field strength (g)”. Confusion leads students write such curiosities as “g = 9.8 m/s2” when the object in question happens to be at rest (for an interval of time). The term “freefall acceleration” also helps to reinforce that this value of acceleration (af = 9.8 m/s2) is only valid while the object experiences the condition of freefall, in contrast to the gravitational field strength (g = 9.8 N/kg) that is likely valid before, during, and after freefall. The units m/s2 and N/kg are interchangeable, but conceptually they represent something very different. This is likely clear to us but not to our students.

- Contact. “Contacting” and “leaving contact with” an object are the precise descriptors we want to use to define the beginning and end of freefall. We might casually say that “a ball is thrown upwards” with a certain velocity, but when we want to nail down precise events, casual language will not suffice. Better is: “the ball contacts the ground with a speed of 7.5 m/s”, or “the ball leaves contact with the racket and then travels 2.5 meters upwards”.

- Release and Drop. What do these sneaky verbs mean? Both often mean to leave contact with an object without any change in the object’s velocity — no push as in the case of throwing — but “drop” often implies a release velocity of zero. That’s a subtle difference. Define these words when you first use them. Or better, make clear what the object is doing the moment it leaves contact. Try “a baseball pitcher releases a 90 mile-an-hour fastball” or “a ball is at rest in your hand and you drop it from a window 1.9 m above the ground.” Overly clever problems where a person releases (or drops?) a ball while ascending in a vehicle of choice (elevator, hot air balloon, airplane) challenge students both linguistically and conceptually. Which should we be trying to test, the language or the physics?

- Metaphors for time. It is really interesting how we use spatial metaphors and speed metaphors to describe time intervals. “How long did it take the ball to reach its highest point?” has a distance word, “long”, representing an amount of time. “The bounce happens very quickly” has a speed word, “quickly”, describing small interval of time. Are our English language learners aware of these idioms? Are teachers? Why not be very clear? Try “how much time did it take the ball to reach its highest point?” or “the bounce happened in a small amount of time”.

- Deceleration. And now we arrive at the most devious word in our students’ kinematic lexicon: the d-word, which I utter but once as a warning to wayward students and then never again. Sometimes a hush falls over the class when a student says the d-word as everyone turns and glares. Colloquially, the d-word is used as a synonym for “slowing down”, often to describe vehicles. However, in students’ minds it becomes tangled with the new idea of negative acceleration. It is common in freefall to have a situation of negative acceleration (acceleration downwards) and the object speeding up — definitely not decXXXXXXing. No better is “speeding up downwards”: a change in a scalar quantity does not have a direction!

How do you solve a problem like freefall?

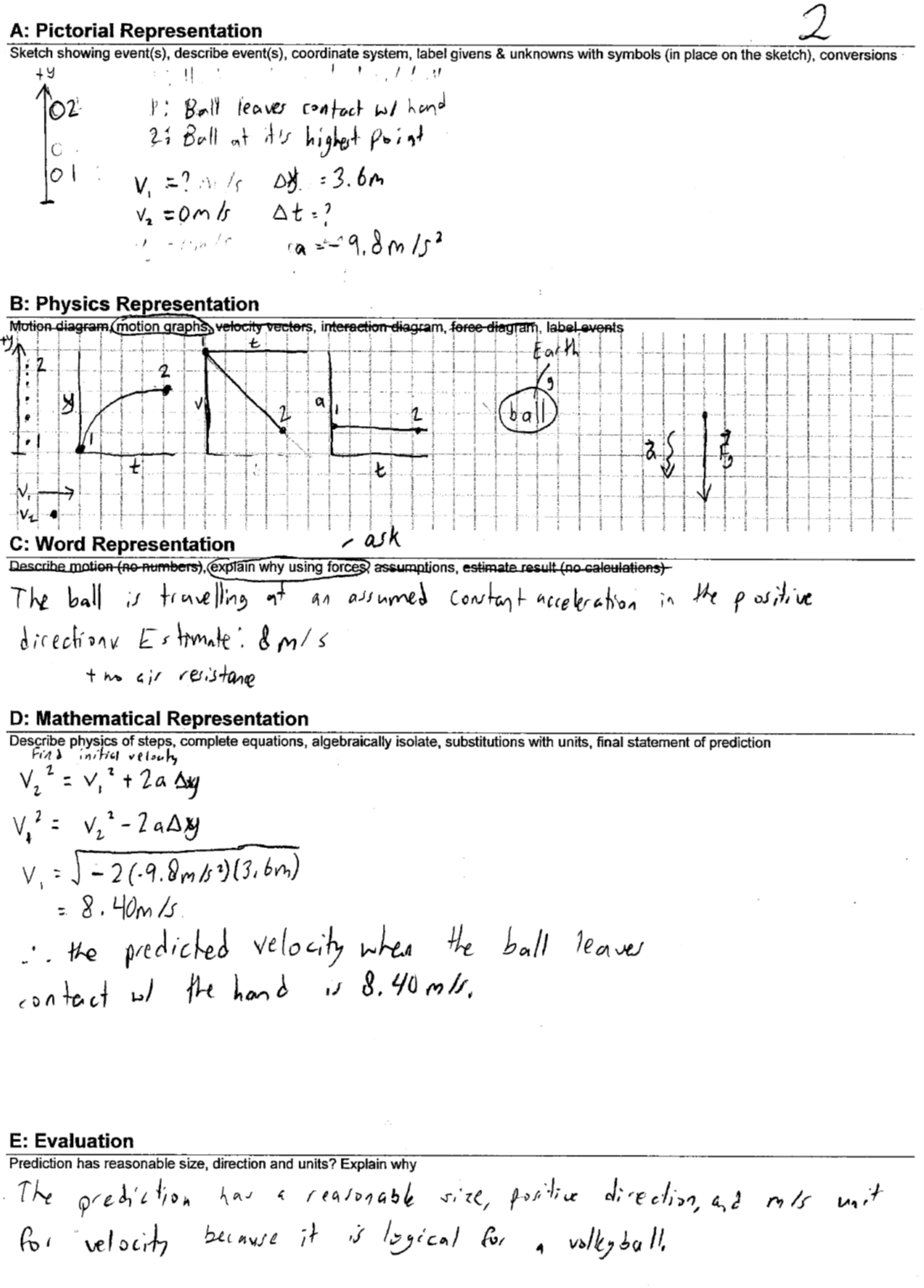

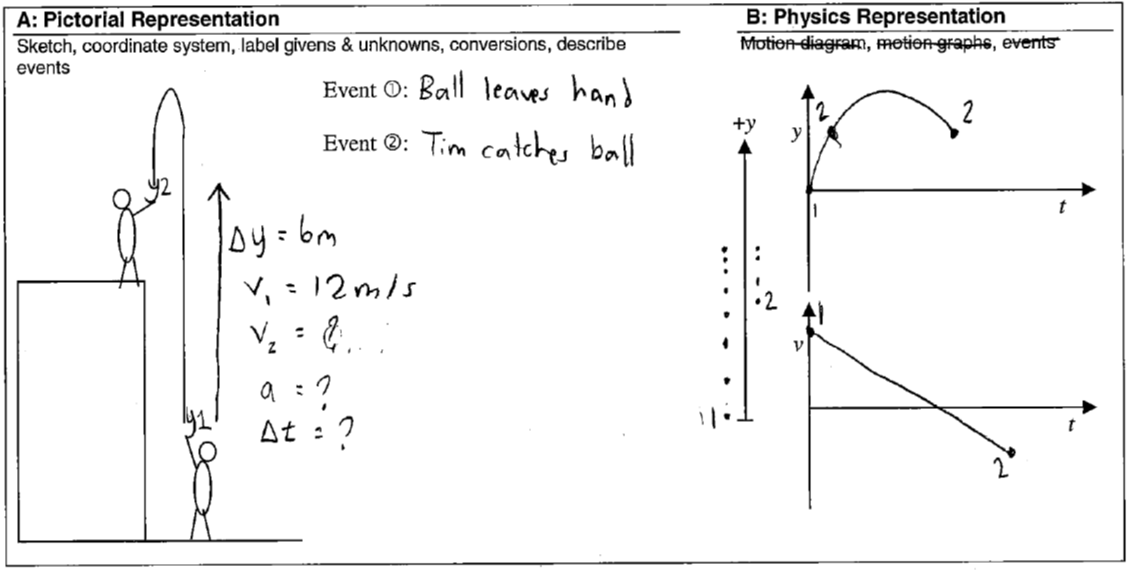

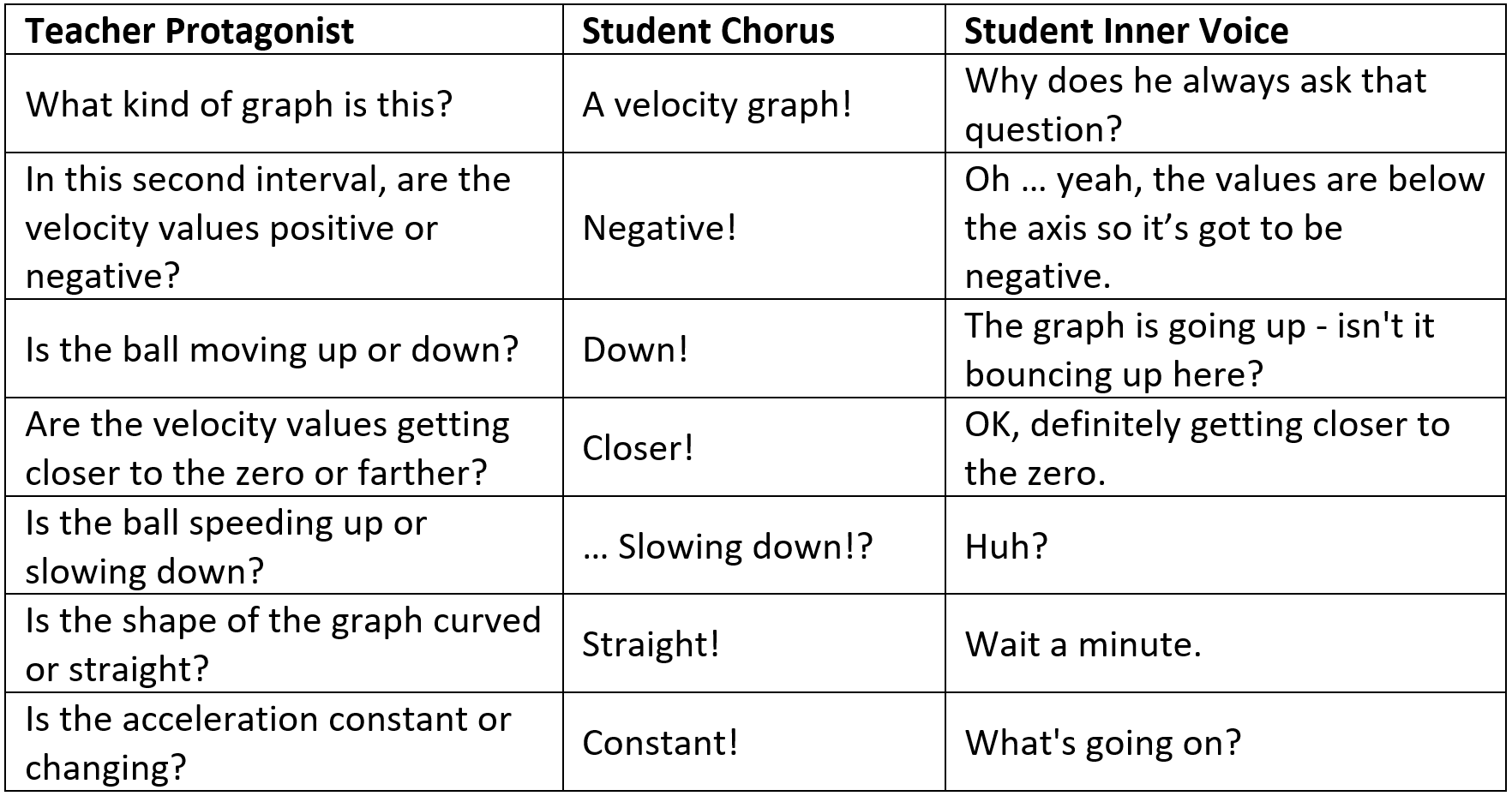

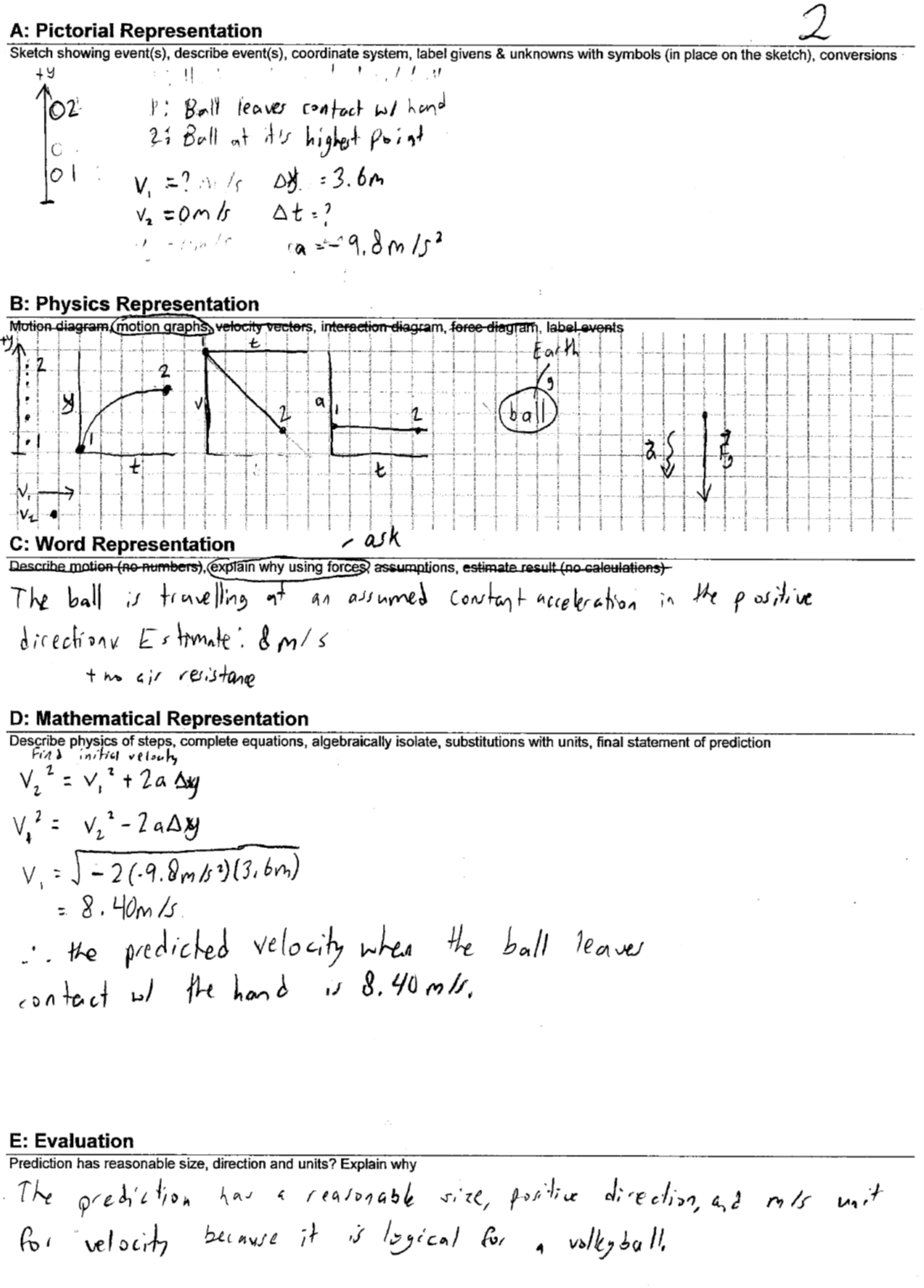

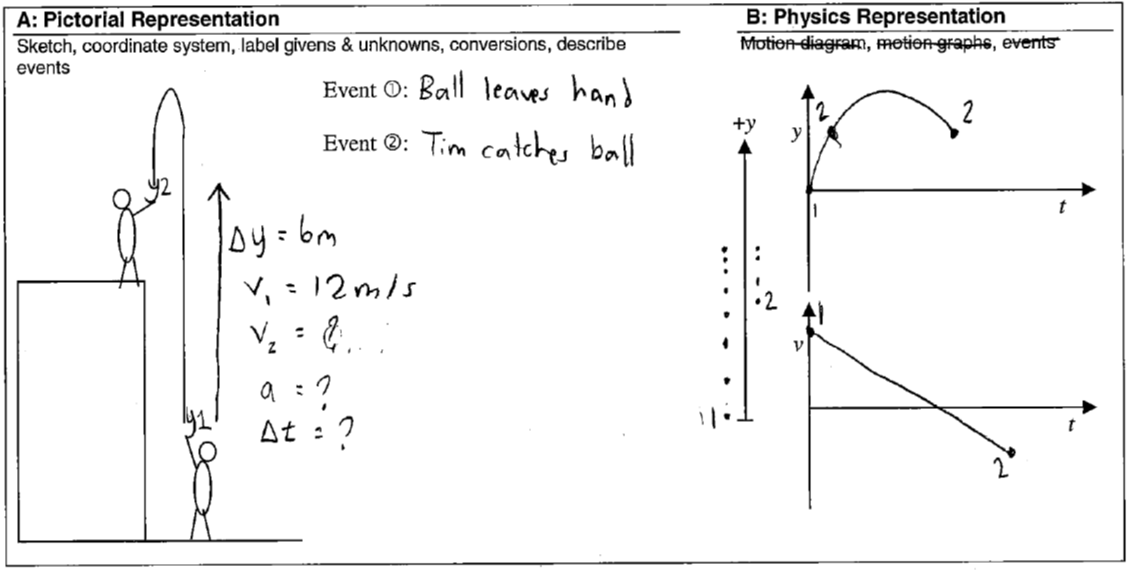

Enough about words, it's time for action! Time to solve problems. Remember that the main challenge is carefully defining the freefall interval. How do we cue good physical thinking about events and intervals? It takes quite a bit of careful practice before good physical thinking occurs automatically, regardless of carefully explained and artful lessons. Students need structure as part of their practice to prompt good thinking. Many of the ideas discussed in this article are featured as explicit steps in our problem-solving process, turning a simple problem into rich practice. Here is an example of this process applied to a single-interval freefall problem:

In Part A students meet the main challenge head on: defining the freefall interval by choosing the key events. Once the events are chosen, students must decide whether they know any velocity values at those moments. The choice of events and the corresponding quantities of motion are then represented in diagrams and graphs in Part B of the solution process, a step that helps check one’s understanding. Notice all the explicit steps that prompt good thinking before students are “allowed” to start with the mathematics in Part D. This rigorously enforced structure is what helps students build reliable thinking processes.

Our first freefall problem

The first freefall problem that my students solve is a two-interval problem, where the interactions change partway through. Students are familiar with two-interval problems from our unit on motion. The homework activity below provides structure for students as they tease apart what happens as a hand throws a ball upwards and releases it.

Who needs the highest point?

Who needs the highest point?

The athlete’s foot of freefall problem solving (mostly harmless, but noisome) grows in dark, moist nooks like this:

Did you spot how my student could improve the description of the events? Most students working through a problem like this will be infected with the idea that there should be an additional event at the highest point of the trip. As a result, students often double their work by breaking up a single-interval freefall problem into two! Why does this happen? You might have some ideas after having read this far! There are a few possibilities: they believe that free fall begins at the highest point; they believe that the force of the hand stops at the highest point; they think the highest point is “important” since we talk about it a lot; or they have not

witnessed the firepower of the fully armed and operational BIG 5 equations) for constant acceleration. For my students, it is likely the latter. At this point in their physics training, they have seen relatively few situations of constant acceleration where the direction of velocity changes. Luckily, the BIG 5 are vector equations, born and raised to handle changes in direction! When the interval has constant acceleration, we choose events based on the moments in time we are interested in. Are we asking any questions about what happens at the highest point? No? Then we don't need that event and we don't need to break up the freefall motion in two intervals. In one fell swoop, a single BIG 5 equation can tackle the problem shown above. This particular swoop is

fell indeed because it leads to a mathematical expression that is second order in time, a quadratic! I mention this because the two solutions that come from the quadratic have a clear physical interpretation in this situation: the time it takes the ball to arrive at a position 6 meters above its start, which happens twice! I have heard more than one student exclaim something to the effect of: “wow, this is just like in math class ... except it makes sense."

Freefalling between the cracks

Don't let freefall, a rich and interesting topic, fall between the cracks in your grade 11 motion unit. The challenges students face while learning this topic are many and touch upon core pieces of our understanding of forces. Carefully exploring freefall within your forces unit will pay handsome dividends throughout high school physics! Feel free to explore the

sequence of freefall lessons my students use and consider trying them yourself!

Tags: Forces, Kinematics, Pedagogy