Chris Meyer, OAPT President

christopher.meyer@tdsb.on.ca

We Can Do Better

For many years I really didn’t know what to do about the obviously small proportion of female students in my school’s physics classes. At the time, I think I managed to convince myself that it wasn’t my problem or perhaps that it was beyond my ability to change. Fortunately, I was wrong on both counts. We can improve the gender balance in our physics classes using two strategies: encouraging grade 10 girls to take physics with presentations and an after-school activity; and encouraging grade 11 girls to continue with physics by directly addressing gender issues.

We Must Do Better

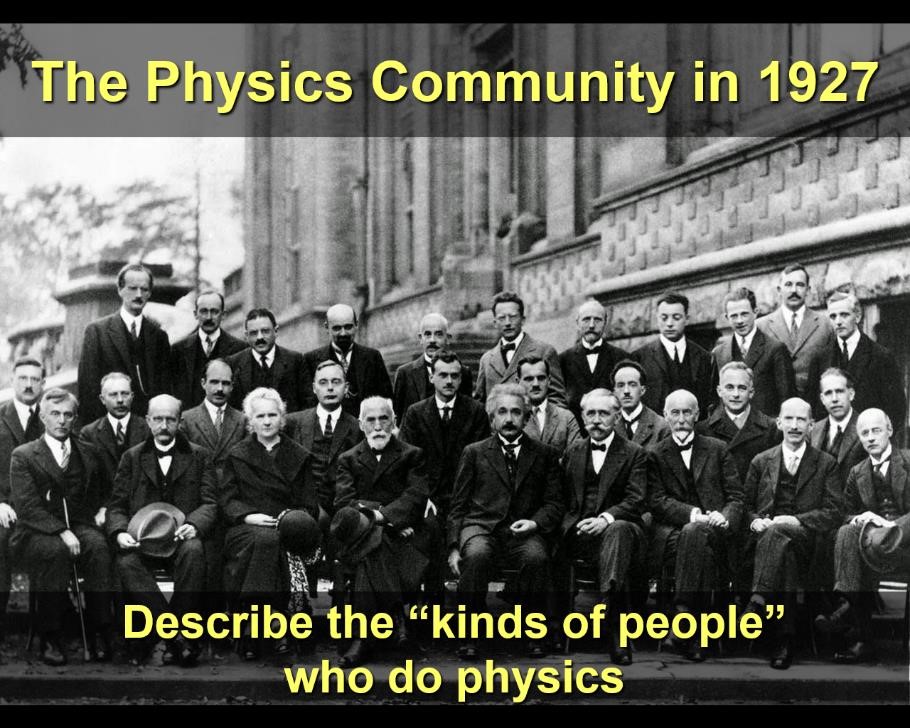

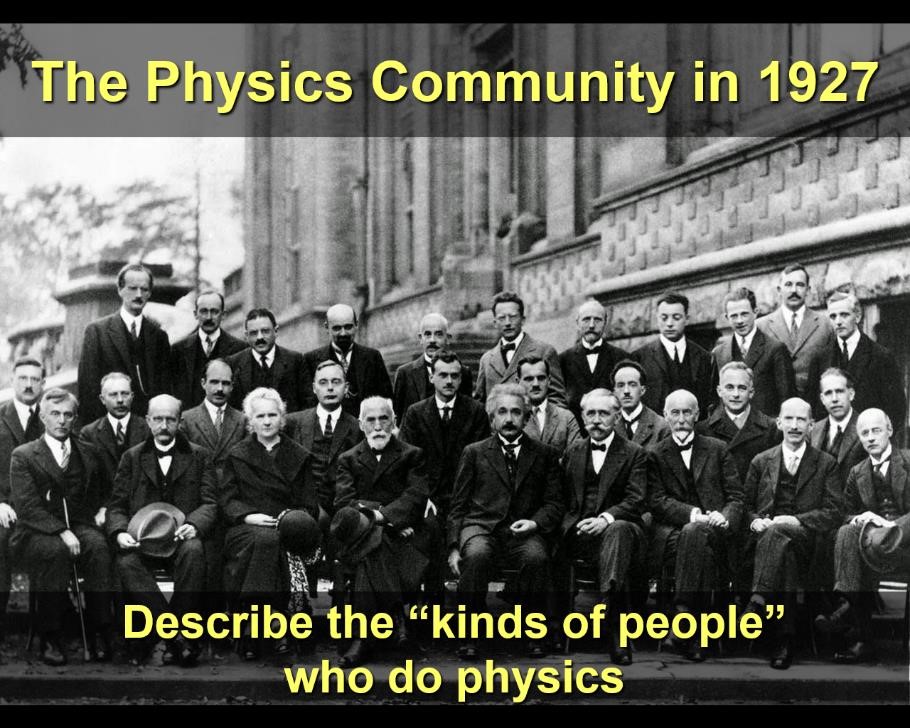

Us physics types like to brag about our problem-solving acumen, yet we handicap ourselves with a lack of diversity in the physics community. Discussions of equity and diversity often get wrapped up in heated political tropes, blinding us to the real issue: the ingredients necessary for solving the toughest problems. The technical problems that humanity faces are becoming extremely complex, so we need a great diversity of people with different life experiences, priorities, and ideas to tackle these challenges. There are no shortage of tragic-comic examples of problems “solved” by people of uniform background or narrow view, for example:

office temperatures and

medical clinical trials. If we believe that we teach something valuable in our physics classes beyond an acquaintance with Newton’s Laws, we should make sure that as many students as possible participate in this experience.

We Must Become Impatient

Engineering faculties across Ontario are working hard to correct the gender imbalance in their profession and are setting their sights on high school physics. The gender disparity emerges between grade 10 science and grade 12 physics where the proportion of females drops from 50% to 32%.

Thank you to Mary Wells, Dean of Engineering at the University of Guelph for this graphic showing the gender proportions in Ontario science and physics classes. Engineering faculties are struggling to come up with solutions to this problem. Some are even considering removing physics as a required course for admissions. For example, the University of Calgary Bioengineering program

does not require physics. Whether this is educationally wise is another matter: engineering faculties want to and will solve this problem, but they will not patiently wait for high school teachers to sort this out. We need to become impatient with the gender imbalance in our classes. This is hard because we have experienced and become used to this imbalance throughout our lives as students and teachers. Maybe we need to imagine we have a daughter in grade 9 (mine is in grade 6) with the clock ticking? How long would you be willing to wait for these changes to happen?

Step One: Encourage Girls to Take Grade 11 Physics

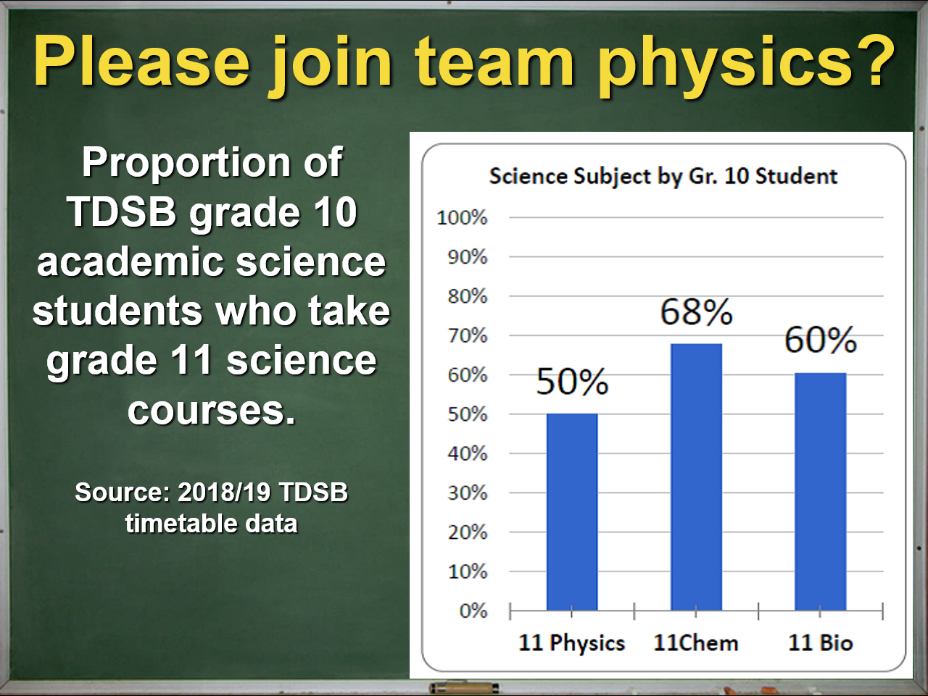

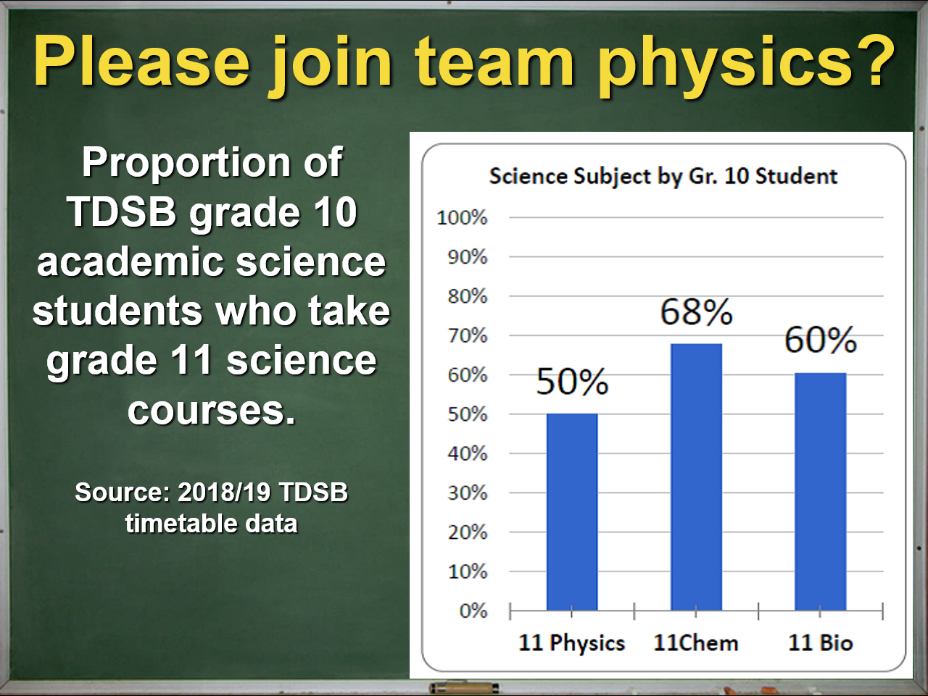

High school physics has the special distinction of being the least popular senior science course and this is often worn as a badge of pride. What proportion of grade 10 academic science students sign up for the grade 11 science courses? Here is my data from the TDSB:

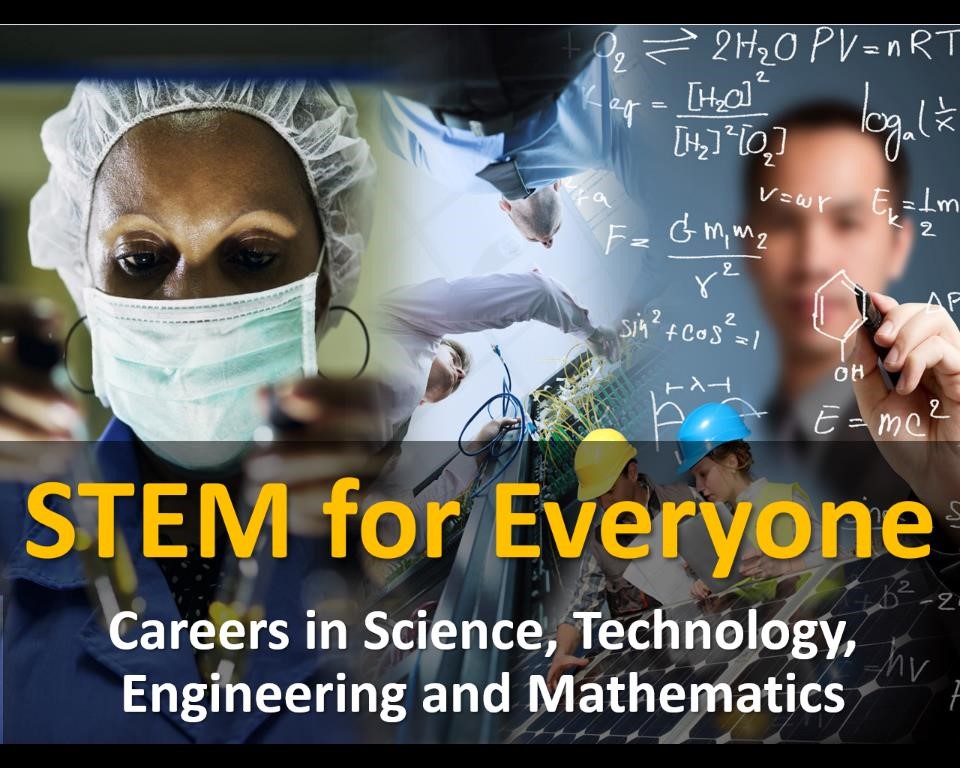

My bet is that most grade 10 students don’t really know what physics is or what doors it opens for STEM careers. Their decision is made using the vague impressions students have of physics in popular culture and the types of people who “do physics”. We can’t change popular culture in one fell swoop, but we can provide our grade 10 students with a different, appealing story. Back in 2017, a group of my grade 12 students and I created our “STEM for Everyone” club. Shortly before course selection, we visited each grade 10 science class and gave a short presentation about STEM careers and the value of taking physics. Here is the presentation:

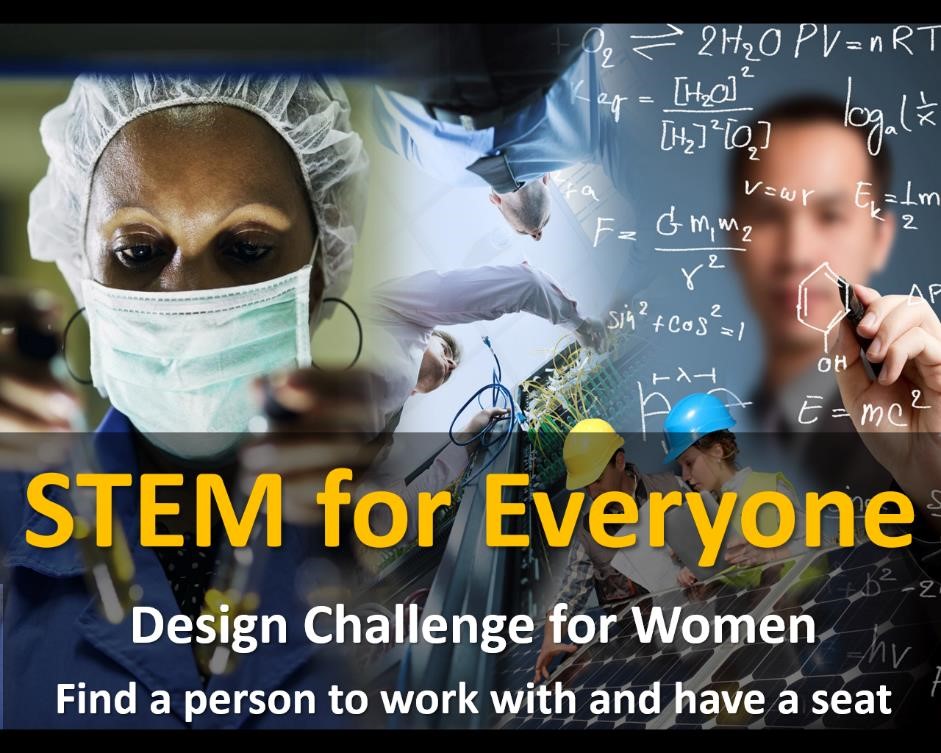

We followed the presentations with an after-school STEM event for girls. The event began with a short presentation on STEM careers and the importance of physics. Next, I got them started on a design challenge inspired by the

work of Roberta Tevlin at Danforth Tech. Here is the presentation I gave and a video of the event:

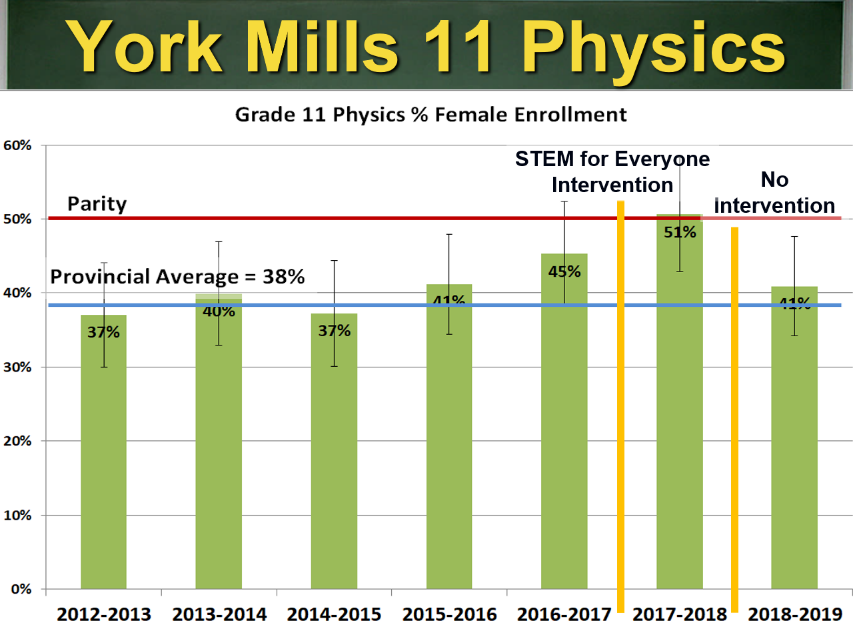

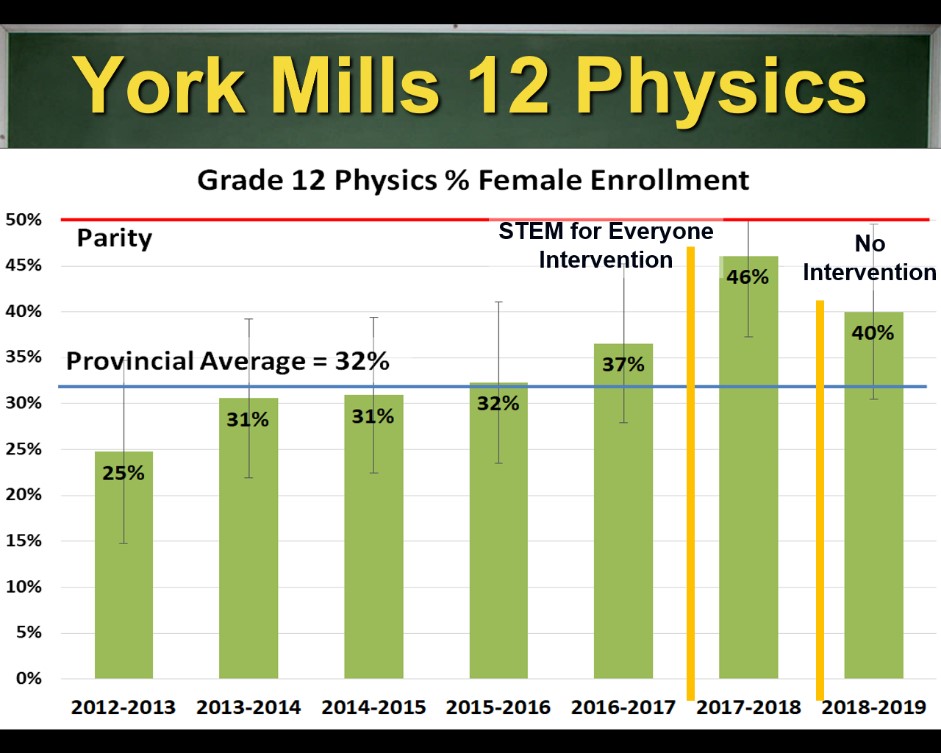

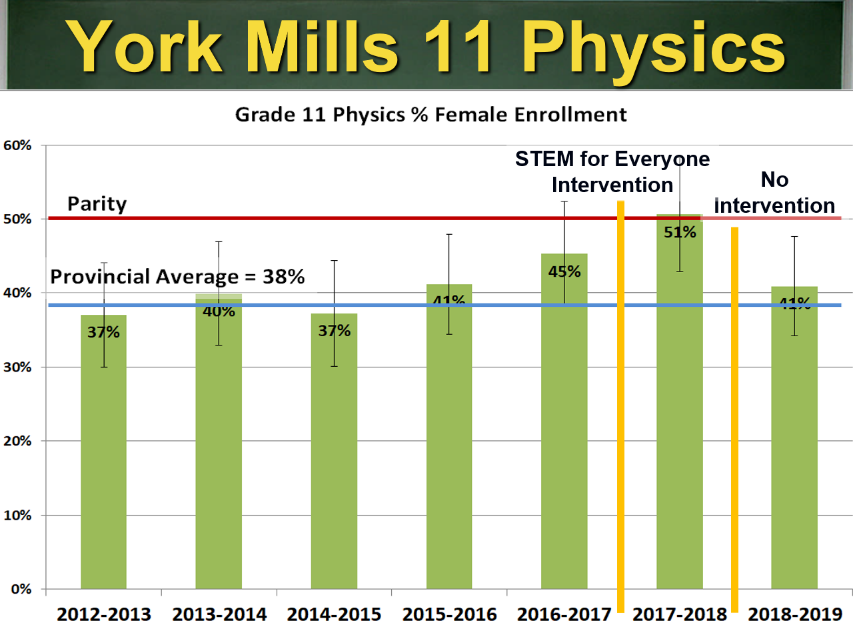

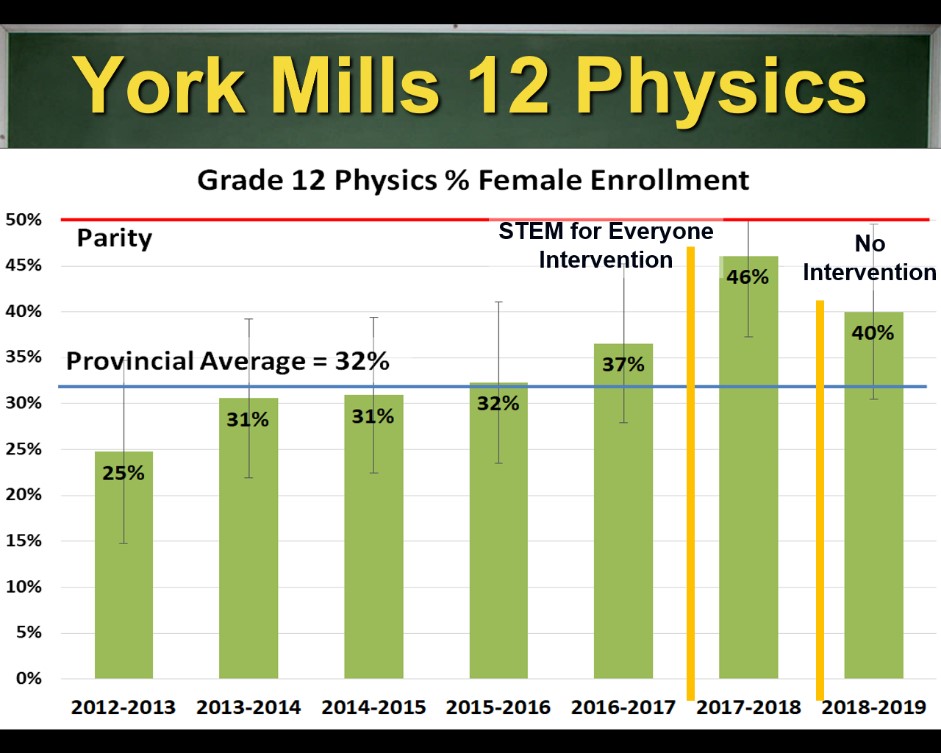

The presentations and event paid off. We saw a clear increase in the proportion of girls in our grade 11 physics class. The following year, the club had dissolved and I did not have a chance to give presentations to the grade 10s. As a result, the proportion reverted toward the norm. This suggests that the intervention had a real effect but must be repeated each year. Here are our results:

Step Two: Encourage Girls to Continue to Grade 12 Physics

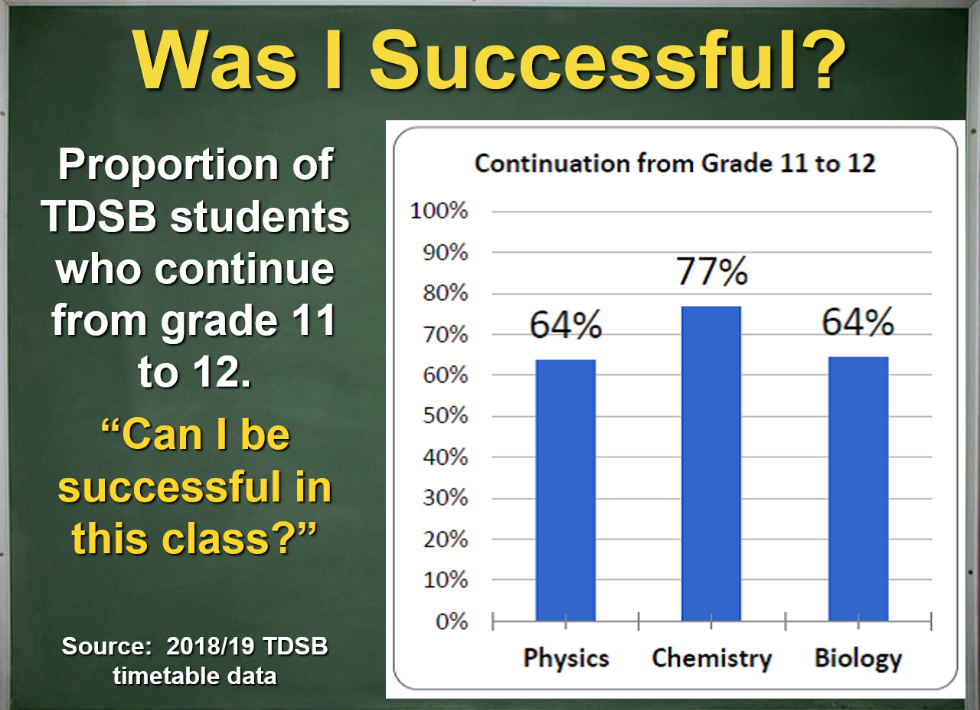

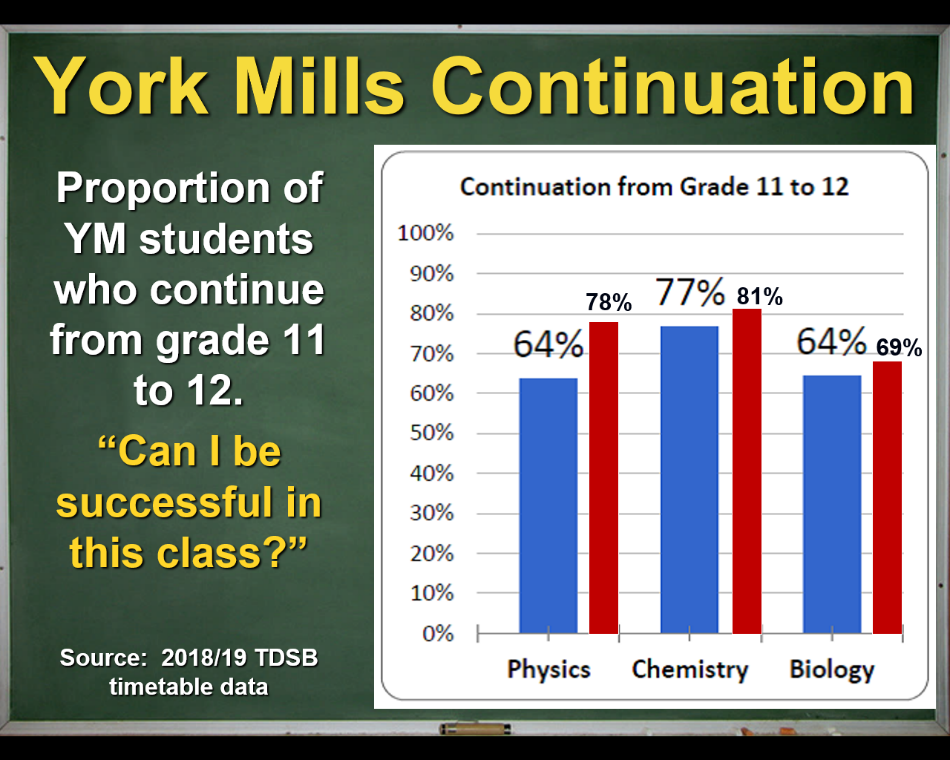

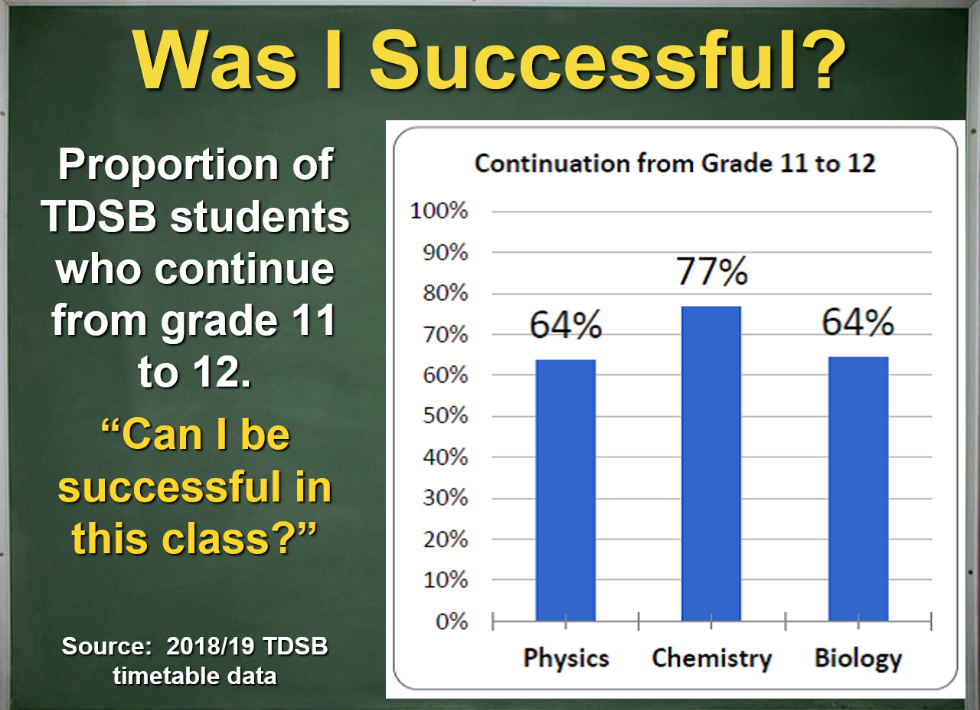

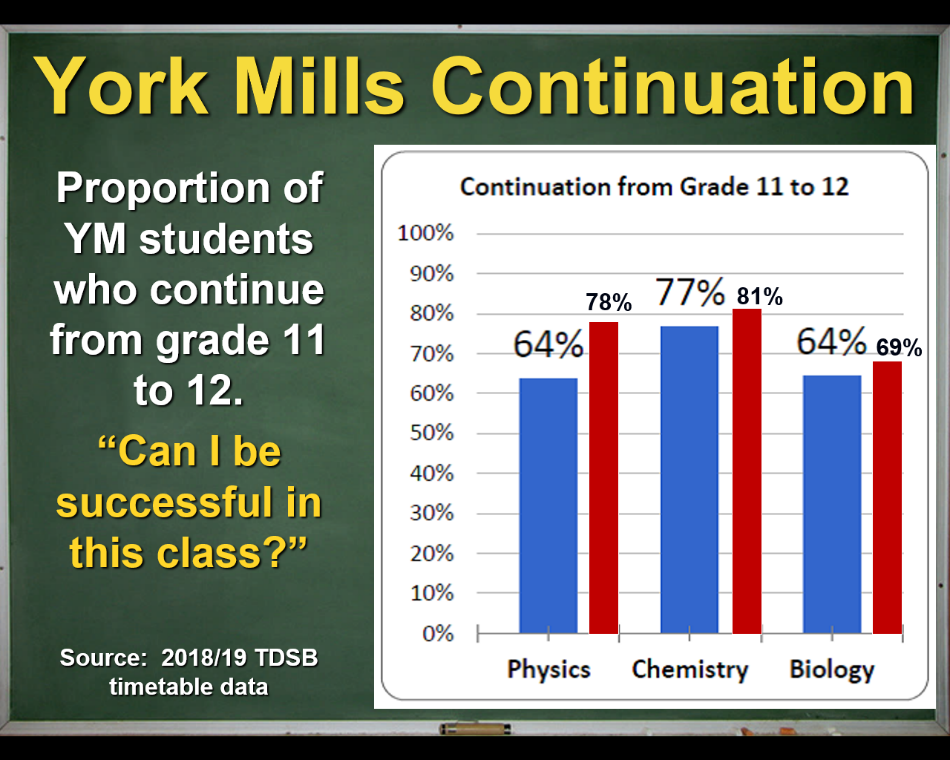

Step one was the easy part: ten short presentations to grade 10s and one after-school event. Once in our grade 11 physic class, students experience real physics teaching, perhaps for the first time. Then we’ve got them right? Here is my TDSB data showing the proportion of students in each grade 11 science course who take the grade 12 course:

Remember that physics lost 50% of the student cohort in the transition from grade 10 to 11. In the next transition, we are losing 36% of our grade 11s. (The chemists win again — what are they eating?) This is often explained as a natural sorting that takes place as we find the right students to pursue physics and engineering in university, but I don’t believe this. Everything that I have learned from physics education research and the science of learning suggests that when learning experiences improve, most students can perform physics at a high level. My hunch is that grade 11 physics is a negative experience for many students, especially female students. Understanding this experience is challenging for us, because it probably differs in significant ways from our own experience learning physics.

Change the Physics Experience

Now we get to the hard part: understanding the experience of many female students (and many students in general) in physics and helping them stay with physics. Research suggests that female students face four challenges in their physics class experience:

- The Brilliance Stereotype: The perception that only very “smart” people can be successful in physics and these tend to be boys.

- Belonging: Not feeling valued as a legitimate member of the physics class – being an outsider.

- Self-Efficacy: Not having the feeling that “I can be successful in this class” or given a task that “I can accomplish this”.

- Math Anxiety: Experiencing greater levels of math anxiety - physics is often taught as a math class.

We have made many changes to the physics program at our school to address these issues. If you are interested, check out the full presentation that I gave on these challenges:

We also address the gender imbalance directly in our third or fourth grade 11 physics class with a short, 10-minute lesson:

At the time of our

STEM for Everyone club, I was bringing up these topics regularly in my grade 11 classes. In our data, we see a bump in the proportion of females in grade 12. After the club ended, the proportion is shrinking.

The improvements we have made are also reflected in our school data (the red bars in the graph below) for continuation from grade 11 to 12, which is well above the TDSB average and has almost caught up with those wily chemists!

Track the Gender Imbalance in Your Physics Classes

Track down the numbers for your science department: ask your admin for past data or use your MarkBook files. Find out how your school compares with the TDSB and the province! And most importantly, challenge yourself to take concrete steps to reduce the gender imbalance in your physics classrooms. All our students will benefit.

Tags: Diversity, Pedagogy