Chris Meyer, President, Ontario Association of Physics Teachers; Hybrid Teacher-Coach, TDSB

Christopher.meyer@tdsb.on.caSo you put all that time and effort into carefully marking the test, including helpful descriptive feedback, and what happens? The student grabs the test, looks at the mark, and tosses it away. Us teachers understand that a test is an important learning experience, but this common student behaviour shows students think otherwise: a test is just a chance for us to deny them marks or sort out the strong students from the weak (a ranking they already know). From that viewpoint, why should a student do anything more than look at the mark and/or complain? And why bother to look at the feedback and make any effort to improve?

Our students’ behaviors often perplex or aggravate us, so it is worth exploring why these behaviours so common. I suspect they are, in part, because our teaching practices actually reinforce them. Opinions aside, what is clear is that unless we explicitly structure learning and improvement into the testing process, it happens only rarely. While we have a lot to do and cover in our courses, helping students improve should be high up on our list. In this short article, I would like to share with you a part of the improvement process my school’s physics classes use for tests.

The Test Improvement Page

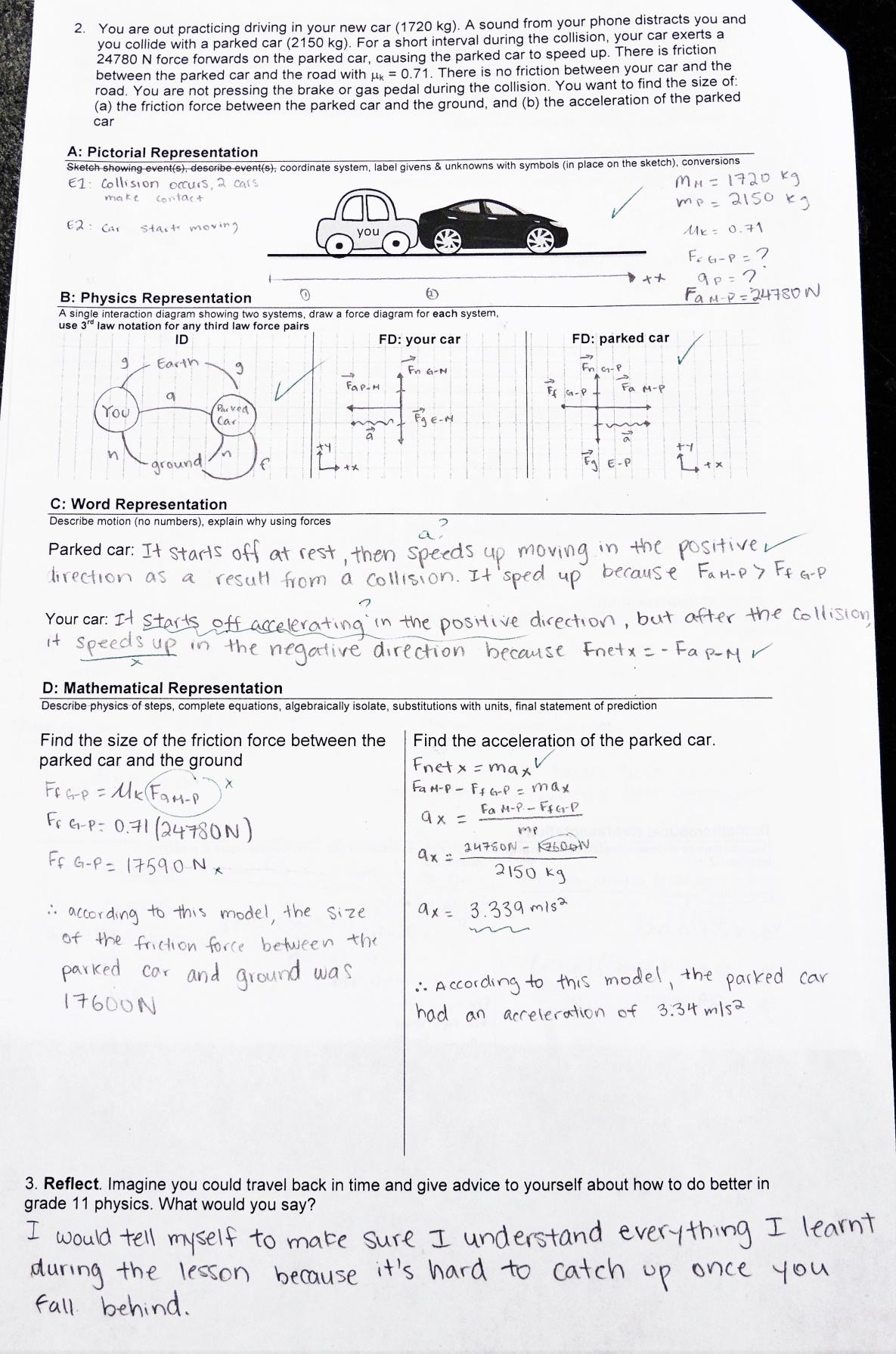

When we hand back a physics test, each student also receives a test improvement page. This page looks a lot like the original test except that it has boxes titled “thinking and improvements” added to each section of the test. The improvement page is an assignment that all students are required to complete, regardless of their mark on the test (all students need to improve). I don't provide corrections or much descriptive feedback on students’ tests. Instead, I indicate what parts need improvement or are missing and provide prompts that serve as a guide. If I do the correction work for them, they won't go through the thinking that is necessary to improve. Remember that old saying: the person who does the work does the learning. A sample test from grade 11, shown below, shows how I mark up the page. On the improvement page, students provide corrected work for all the sections of the test that I have marked up. Anything that was fine, they leave blank.

There are two necessary ingredients to start a process of improvement: figuring out the right answer or idea, and understanding the thinking process that led to the original error or omission. The latter is an important part of the neglected skill of metacognition: monitoring one’s thinking processes and assessing the quality of one’s own work. Improvement is very difficult if the habits of metacognition are not consciously practiced (the topic of my previous article). The “thinking and improvements” boxes on our test improvement page are intended to prompt metacognition. In the boxes, students describe their original thinking and describe what ideas or skills they need to improve.

A Helpful Aside: Evaluating Student Work

I mark my students’ test improvement pages using a simple marking scheme: if further improvement is necessary, I write “fix!” at the top of their page and explain to the class that this means a zero has been recorded until corrected work is submitted; and if the improved work is good, they get 100% for that assignment (for unimportant historical reasons, I give them a 2 out of 2). This approach is part of a shift in my thinking about how I evaluate daily student work. Our evaluations, the marks we “give”, form the rules of an educational game that many students play. I want my rules to encourage the best possible learning behaviours.

Aside from my high falutin’ rationale, I’m also just tired of students producing crappy work and getting away with it. And by that, I mean getting a marginal passing grade and moving on. The level of work that gets a 60% (for example), is often work that is not useful preparation for further study or would not serve as an acceptable product in the working world. Our tacit approval of this level of work (granting a credit for it does connote approval) reinforces unhelpful learning behaviours. For this reason, I have been taking what might be described as a mastery approach towards evaluating my students’ daily work (my approach for tests and quizzes is different still). This means that students’ work must meet a fairly high standard before being considered “acceptable”, a level roughly equivalent to an 85% or 90% in the past. This high standard represents work with no significant errors in content or communication. If work is not acceptable, I write “fix!”, add a few markings, and return it to the student who I nag and harass until the improved work is submitted and gets 100%.

This might sound like a time-consuming process and on one hand it is, but it is also a time-saving process. I used to agonize over the determination of precise marks because I knew students would ask me about them: is this worth a 3.5/5, a 4/5, or a 4.5/5? In retrospect, this took quite a bit of my time. Now, my time and energy is better aligned with my students’ learning. My initial evaluation of their work is very quick, saving me time: the work is acceptable (no significant errors) and gets 100% (no arguments), or it is not and gets “fix!” and a few markings. I do spend more time tracking students’ submissions and often see their work two or three times, but learning is actually happening. Deciding if it’s a 7.5 or 8 out of 10 is not useful effort. Simple test: does anyone’s learning improve because of that effort? (Answer: no)

This shift in approach does take some getting used to, but my students have responded well to it. Their work on the test improvement page is usually reliable and diligent. I don’t see many examples of students doing sloppy, random work to make it look like something has been done; that would lead to a zero because it gets sent back to them. It is possible for a student to copy good work from another student, but that’s actually OK. At the very least, this student now has corrected work to refer to for future studying. However, the metacognitive prompts in the boxes and my lack of corrections do require a basic level of processing on the students’ part and that usually leads to good thinking and genuine improvement. A good majority of my students work very carefully on their improvement page. Of course, there is no magic bullet that works perfectly for every student, but when something works so well for so many, it’s worth it.

Examples

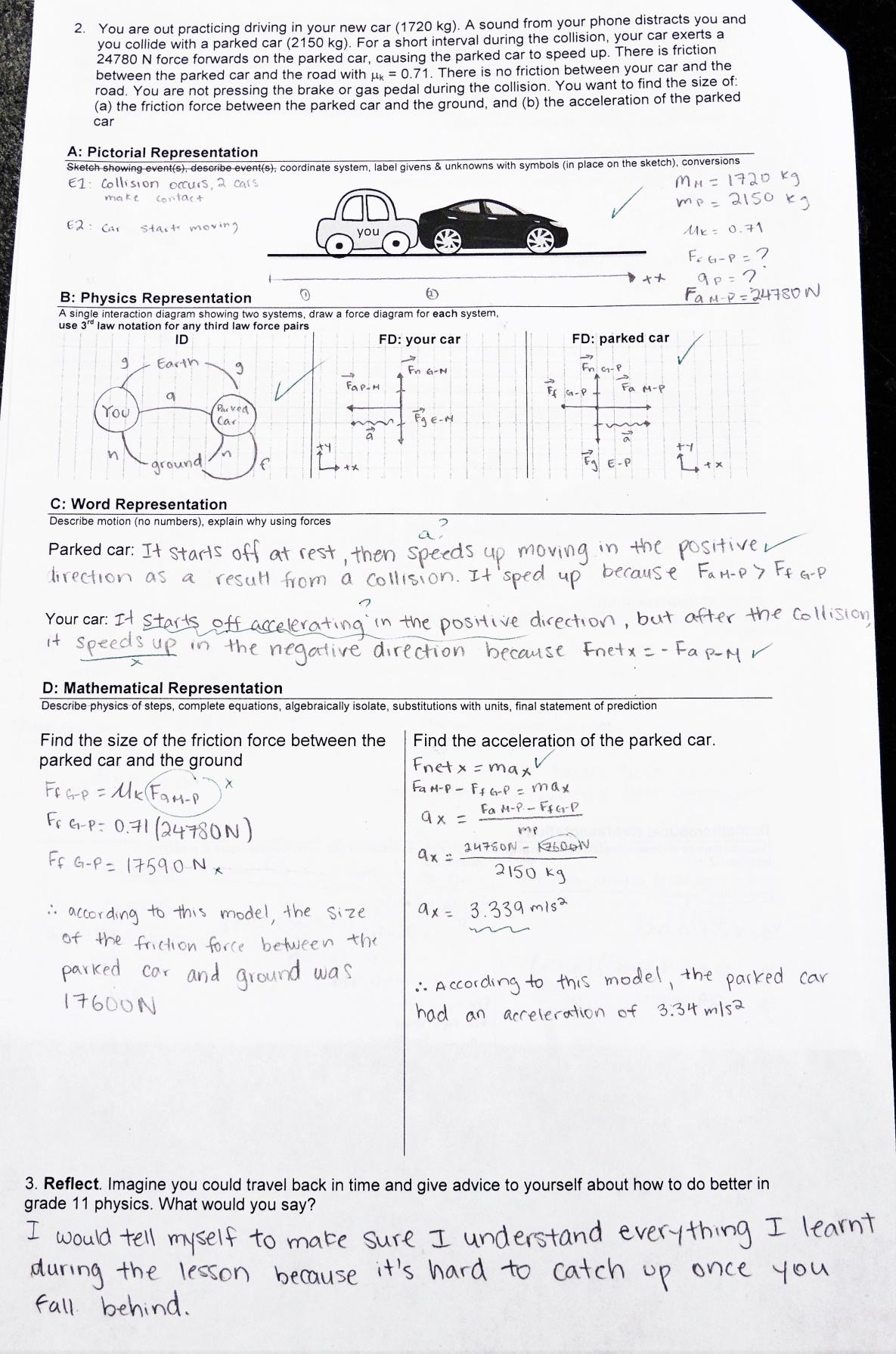

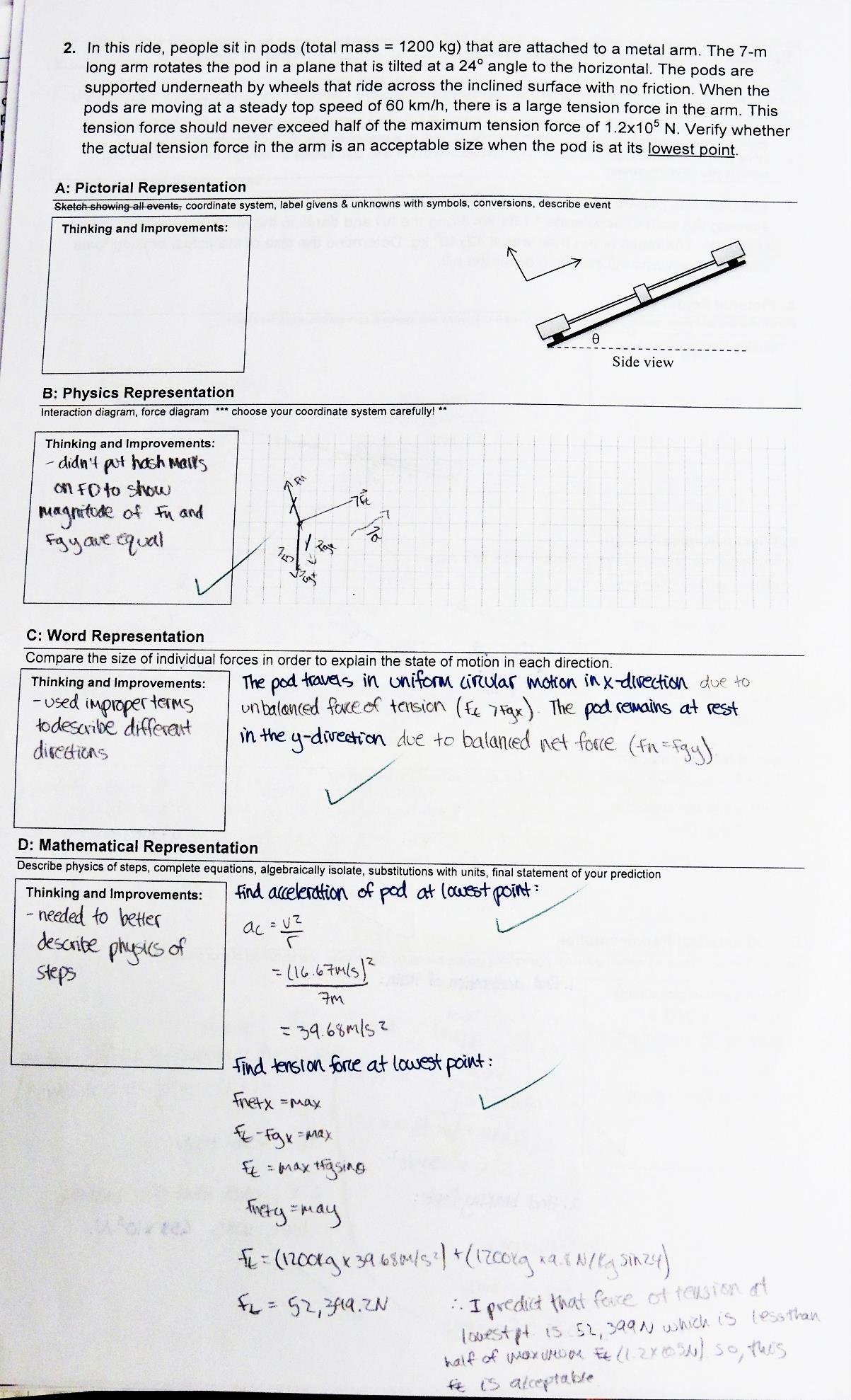

Here are a few samples of grade 12 students’ test improvement pages that I thought were interesting. The first example below shows the full improvement page (both sides) and gives you a good look at the style of our tests. Please note that not all the question information is reproduced on the improvement page. This student did a great job of her improvement page on her first attempt (a 2 out of 2). Her improvements are carefully written in a different colour (as per my instructions) and most are fairly minor details. Parts of the improvement page are blank because the student did fine on those sections.

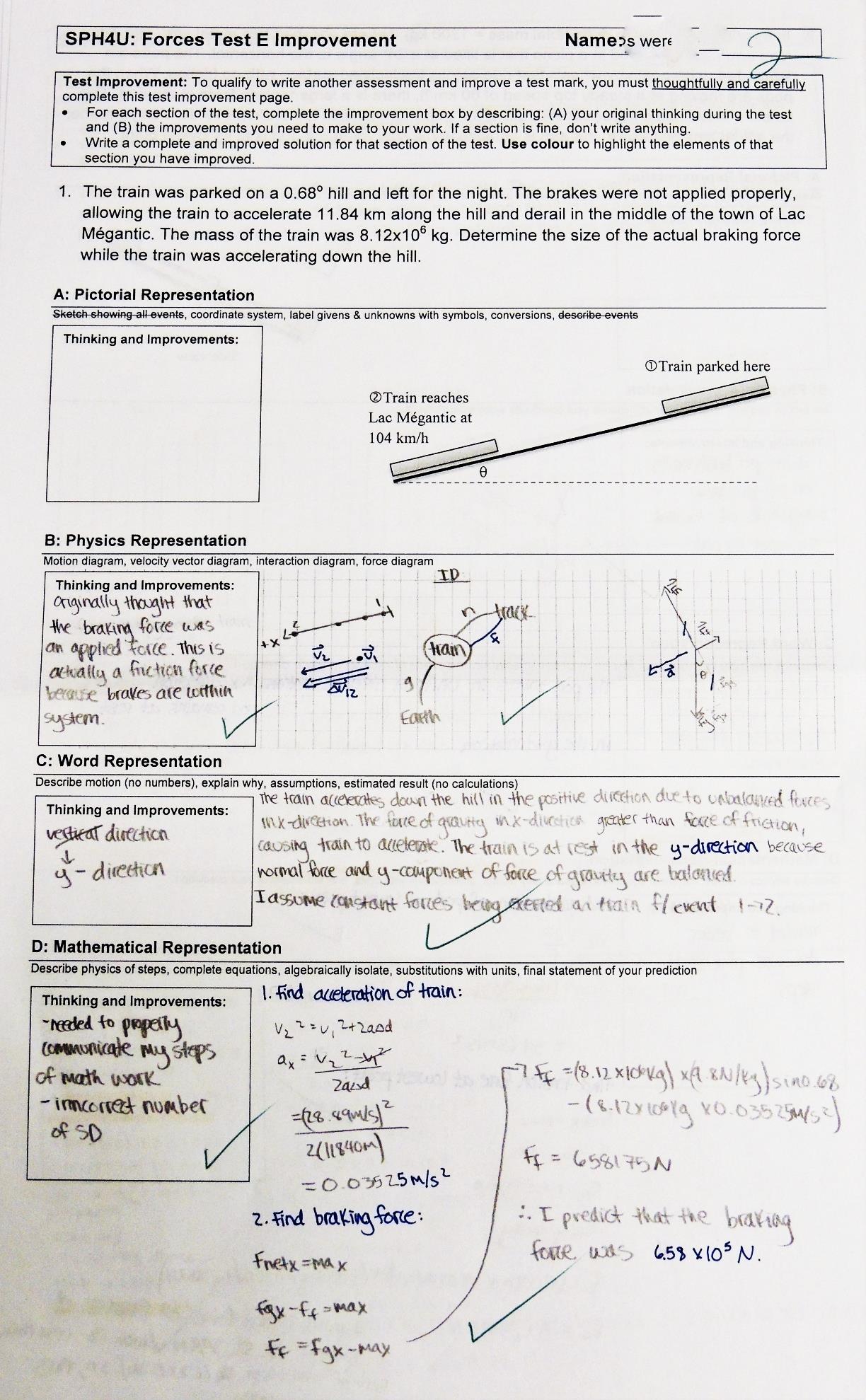

On this test, many students referred to the x- and y-directions of the tilted coordinate system as the horizontal and vertical directions, which is just plain wrong. This was corrected in the previous example.

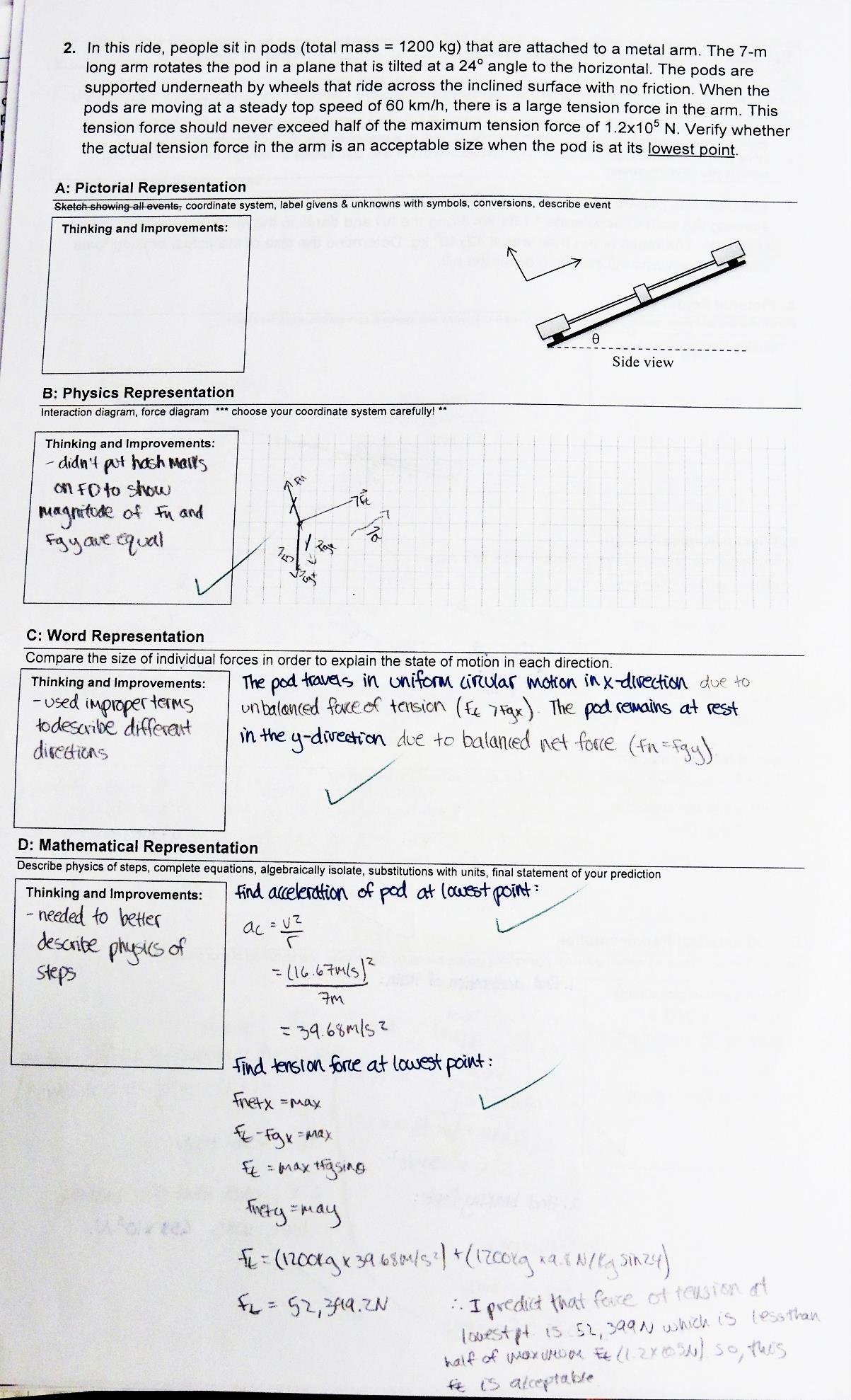

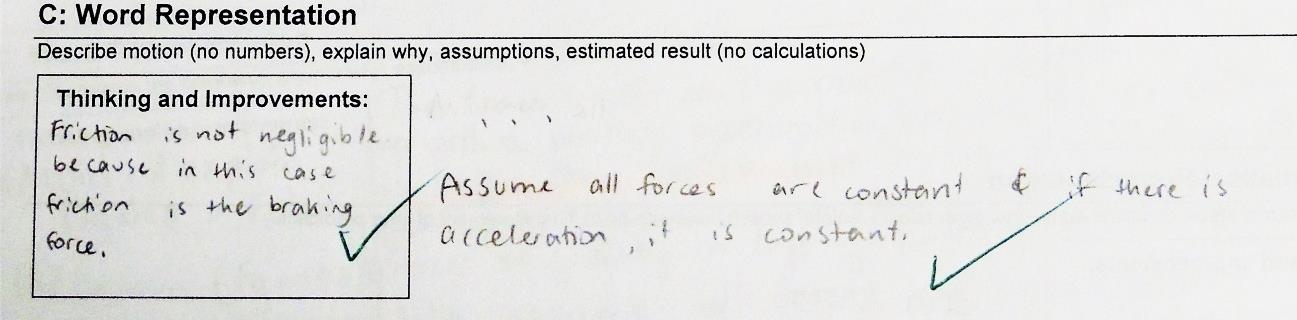

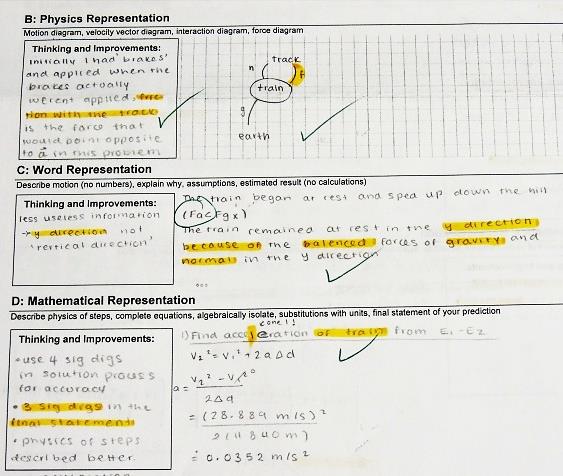

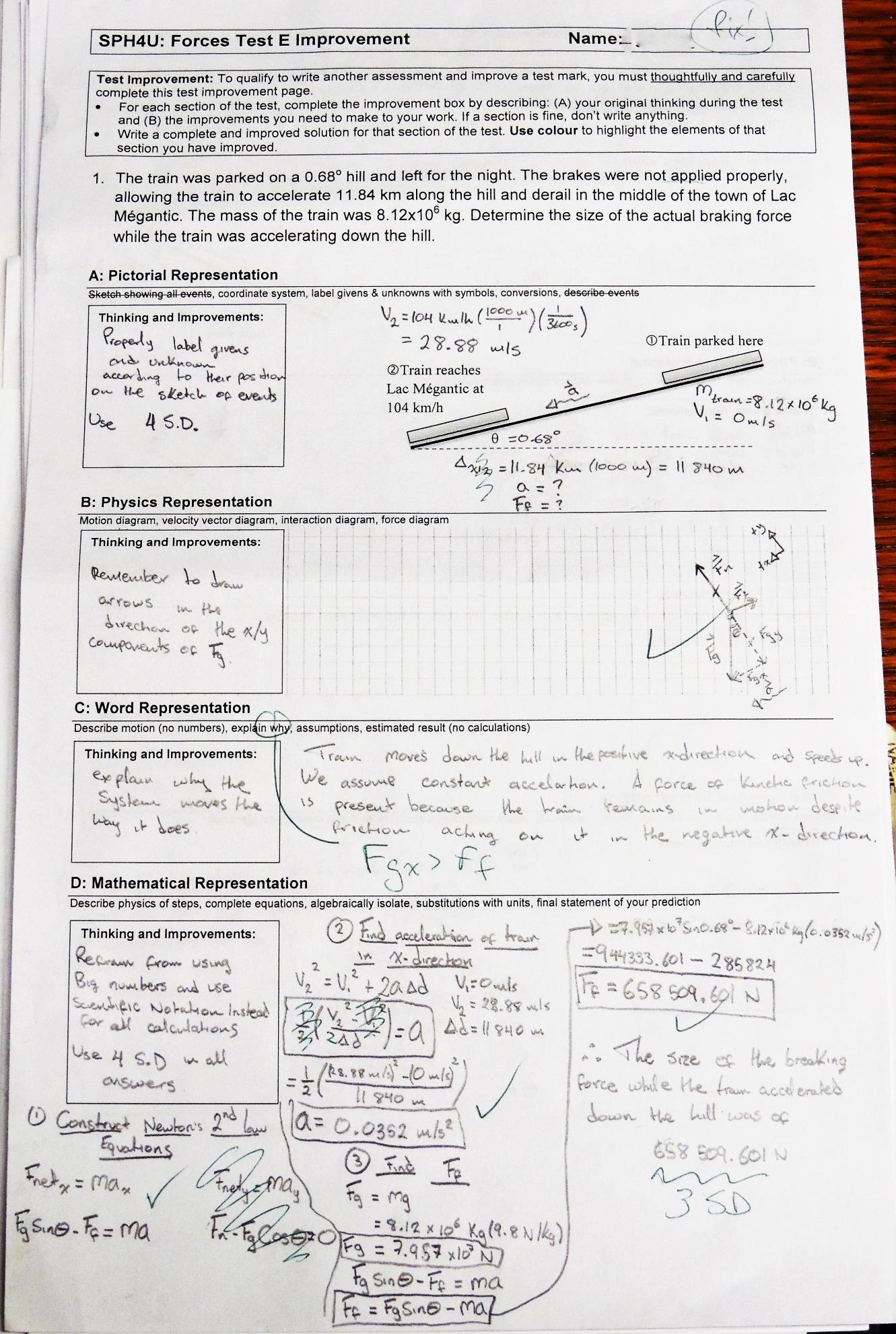

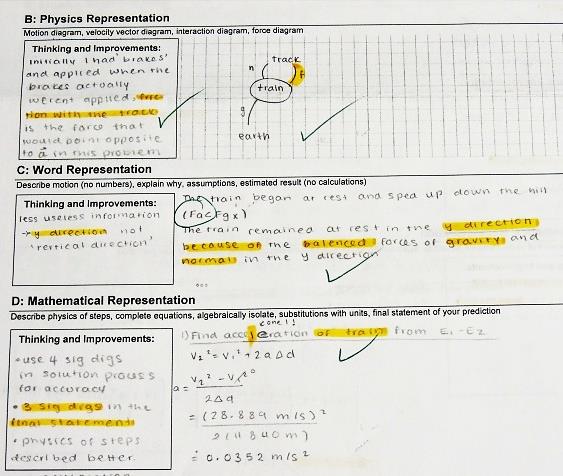

In the next example, the student demonstrates good metacognition through the descriptions in the boxes. The level of work is very high, but there is more to improve! My feedback is brief or cryptic (3 SD means they should write the result using three significant digits, our standard practice for statements). In one place, I figured the student needed more specific guidance and wrote “Fgx > Ff”, which they still have to decode and write out. I am also concerned when student’s work is not concise. Some of my markings hint at what can be eliminated – another valuable improvement!

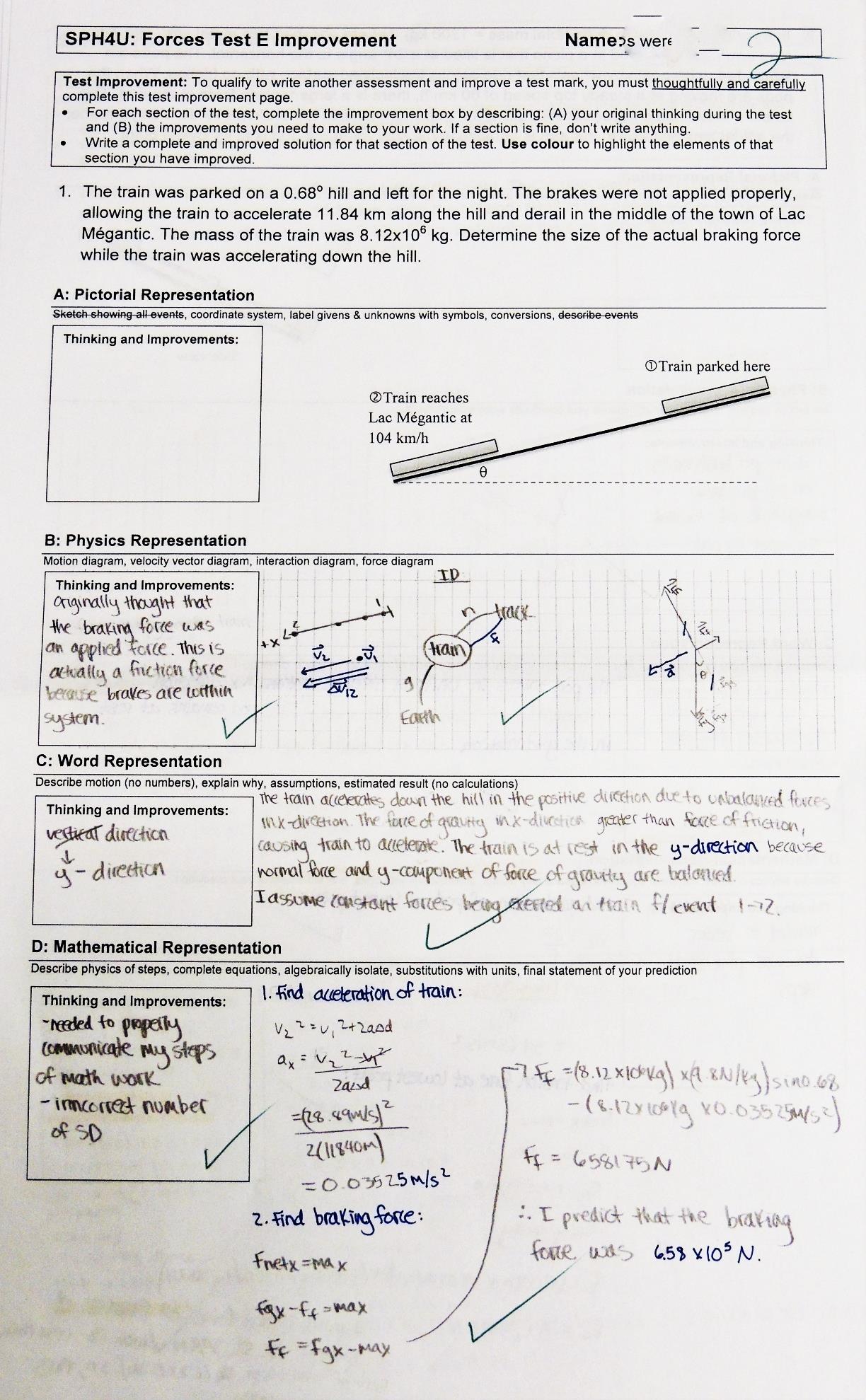

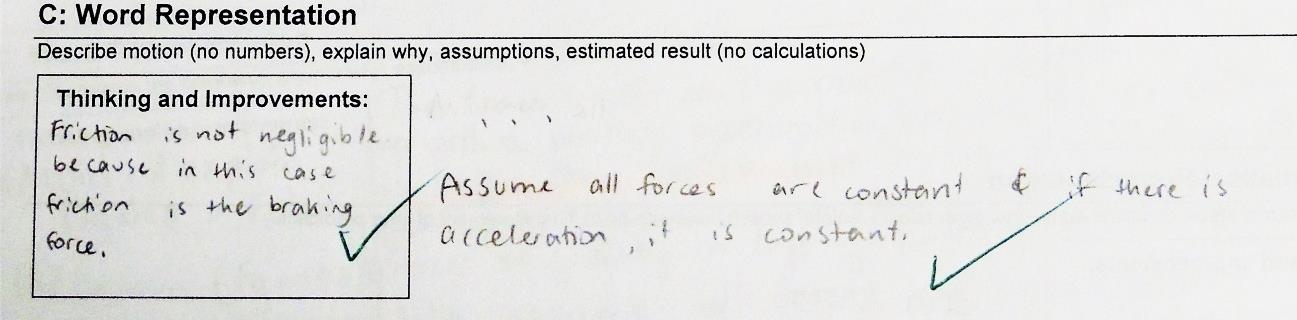

In the next example, the student had a perfect test score, but still had an improvement to make. Her improvement page is blank, except for one section:

This test question was about the Lac Mégantic train disaster. Many students didn’t identify the braking force as an external force of friction.

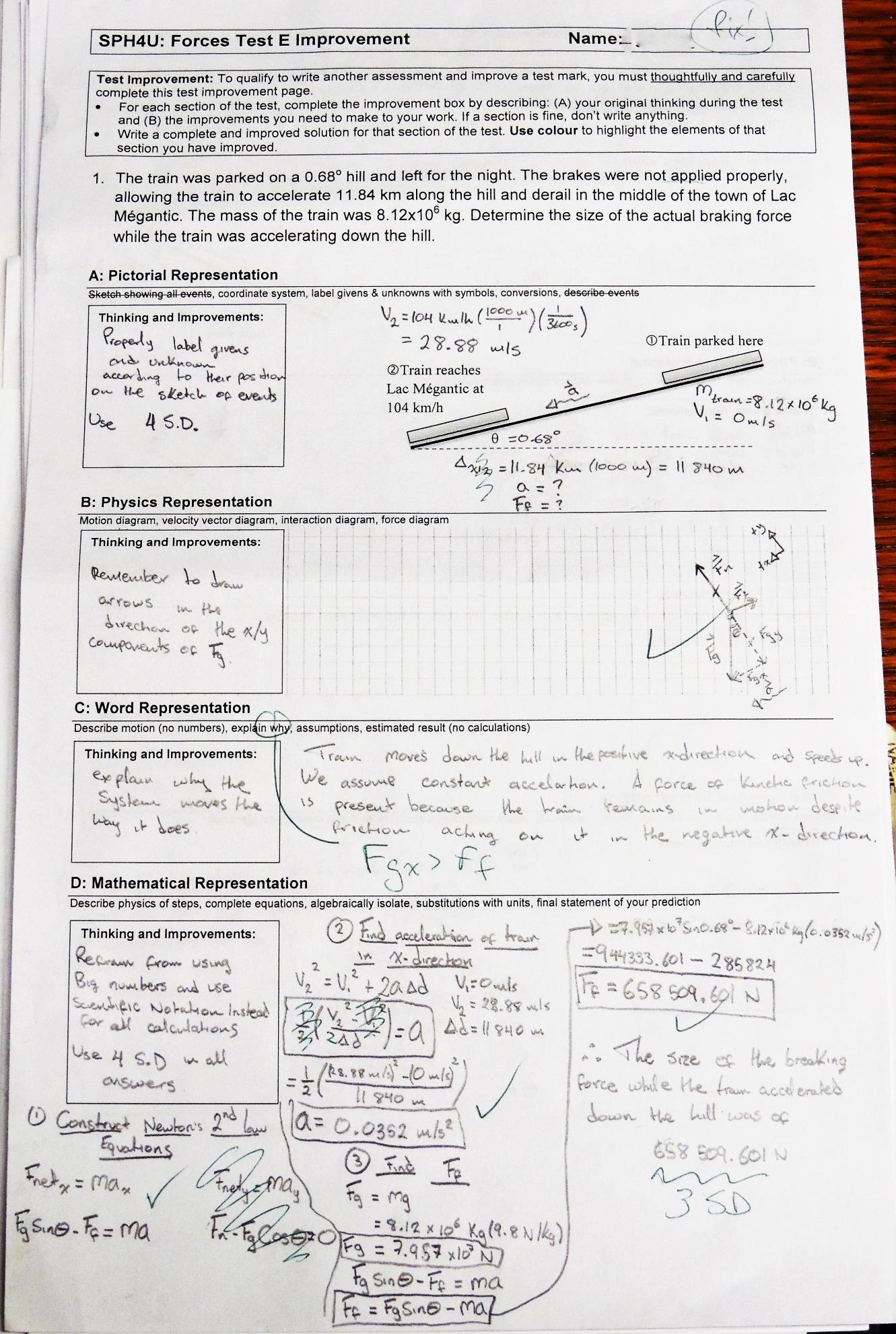

The final example illustrates great metacognition and an improvement in spelling (which I always indicate: scientific work must be spelled correctly! can you find the correction?) Can you identify the one remaining improvement this student had to make?

Build Improvement into Your Course

The long and the short of it is this: we need to integrate improvement into students’ learning experience in our classes. Otherwise, it only happens haphazardly and sporadically. To maximize its utility, improvement should happen right away so students can benefit from their improved skills and understanding in subsequent work. This positively reinforces the value of the improvement process, helping students to take it more seriously. It also puts our educational money where our mouth is: our job is to help students learn and this helps (moving on to more content doesn’t). Finally, students should be rewarded for successfully using productive learning behaviours; pretty much all my students get perfect on this assignment and other pieces of daily work. And in addition, our students, after presenting evidence of improved skills, have an opportunity to improve their actual test mark, which will be the topic of a future article!

If you are interested in our test improvement process, you can download a copy of the grade 12 test, which includes the improvement page at the end, right here:

https://drive.google.com/open?id=1nGC4dzfQG3CaF1kX5QOiebv3Um05tkvaTags: Pedagogy