Chris Meyer, York Mills C. I., VP Teaching and Learning, OAPT

Christopher.meyer@tdsb.on.caHave you had a conversation with a student that went something like this?

Student: “I need a 90% in physics in order to get into engineering at ...”

Teacher (outer voice): “Well, I’ve noticed that your homework is often incomplete.”

Teacher (inner voice): “!!?!?”

Student: “I know. I’m going to work really hard now.”

Teacher (outer voice): “You need to catch up with all the material you had difficulty with back in grade 11, especially forces and motion.”

Teacher (inner voice): “Buddy, you slacked off all through grade 11. You have no idea how tough this will be .... In two months there’s going to be tears.”

Student: “OK. Thanks, bye!”

I have had this conversation more than once and I am willing to bet you have too. This student is also very likely to drop at midterm, hoping to take the course again next semester or in night school. I have long wondered about the cause of this behaviour and how students come up with such wildly unrealistic academic expectations. In the past, I have indulged in blaming the “culture of entitlement”. You might be familiar with this refrain: throughout students’ education they have been rewarded for slacking and mediocrity, they get a prize just for showing up and looking pretty; so it’s hardly surprising that such unrealistic expectations are common.

This cultural problem seems to be beyond the power of any one of us to fix, but I don’t believe so. Clearly, there is a mismatch in the student’s mind between expectations and “reality”. Rather than worry about the source of this mismatch, we should focus on correcting it, but how? It dawned on me that these students likely don’t know what it means to “be a 90’s student”. They see other successful students in class who magically get the 90s. To the mark hungry student, it can all seem very unfair: their aspirations in life are just as important, they are equally deserving, but somehow they are being “denied” the marks that others “effortlessly” get. (Right? They actually know the material: we just picked the wrong questions for the test, which denies them their marks.) So much of learning happens almost invisibly or at least beyond a typical person’s sphere of attention that we shouldn’t be surprised that this is a common attitude. I can recall as a piano student, after my recital performances many conversations something like this:

Very Nice Person: “I really liked your performance. You must be very talented.”

Me (outer voice): “Thank you, I’m glad you enjoyed the performance.”

Me (inner voice): “Yeah, well I worked my frickin’ ass off. Try it some time.”

I have mellowed since (the talent comment has always bothered me), but I hope you get my point. The average student (or concert goer) is simply not familiar with the intense level of effort and the sustained practice of skills that leads to consistent, high-level performance. But there really is nothing magical going on. I think this is the most important part of the goal mismatch students might have and is something I think we can address. We need to train students in what it means to “be a 90’s student” and help them understand what skills and habits are necessary to get there.

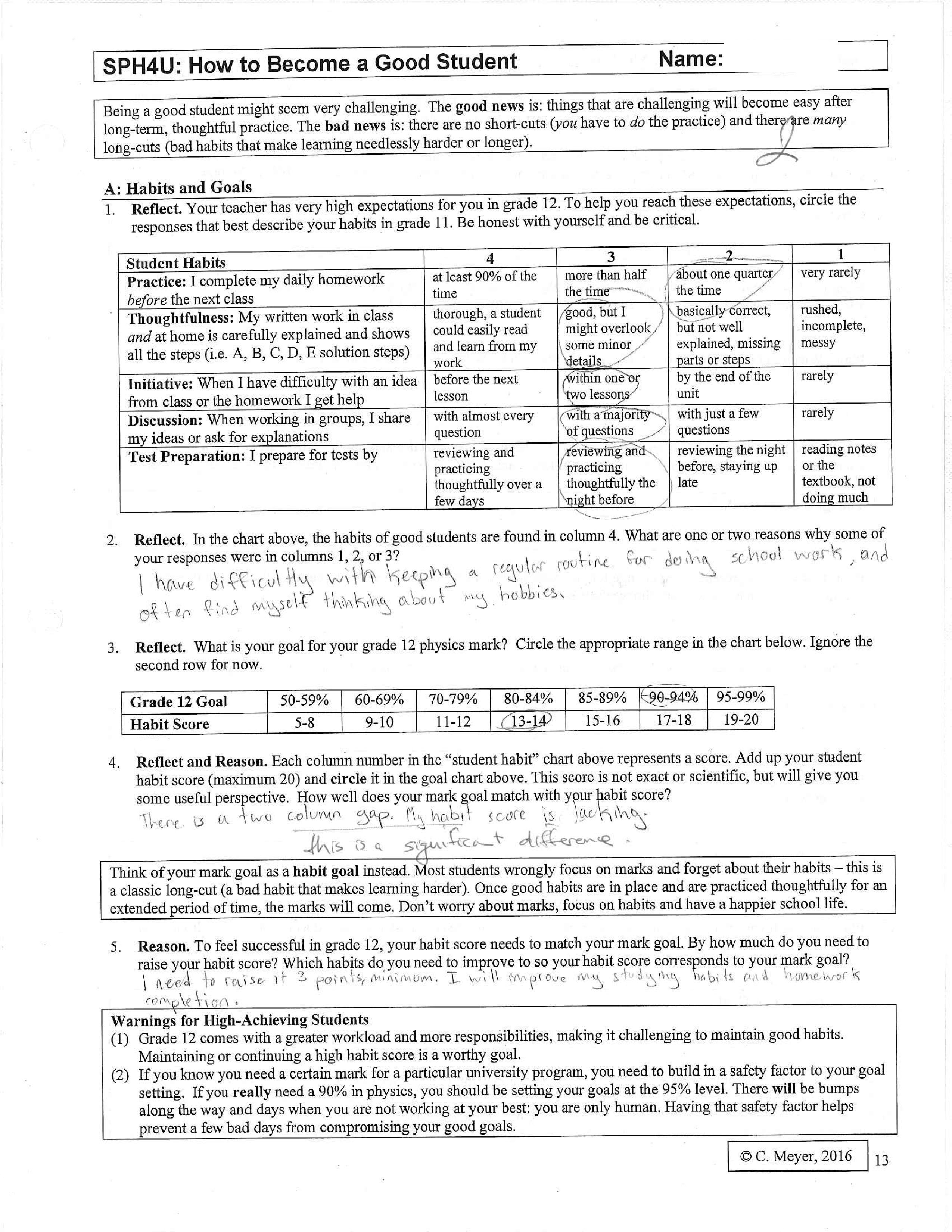

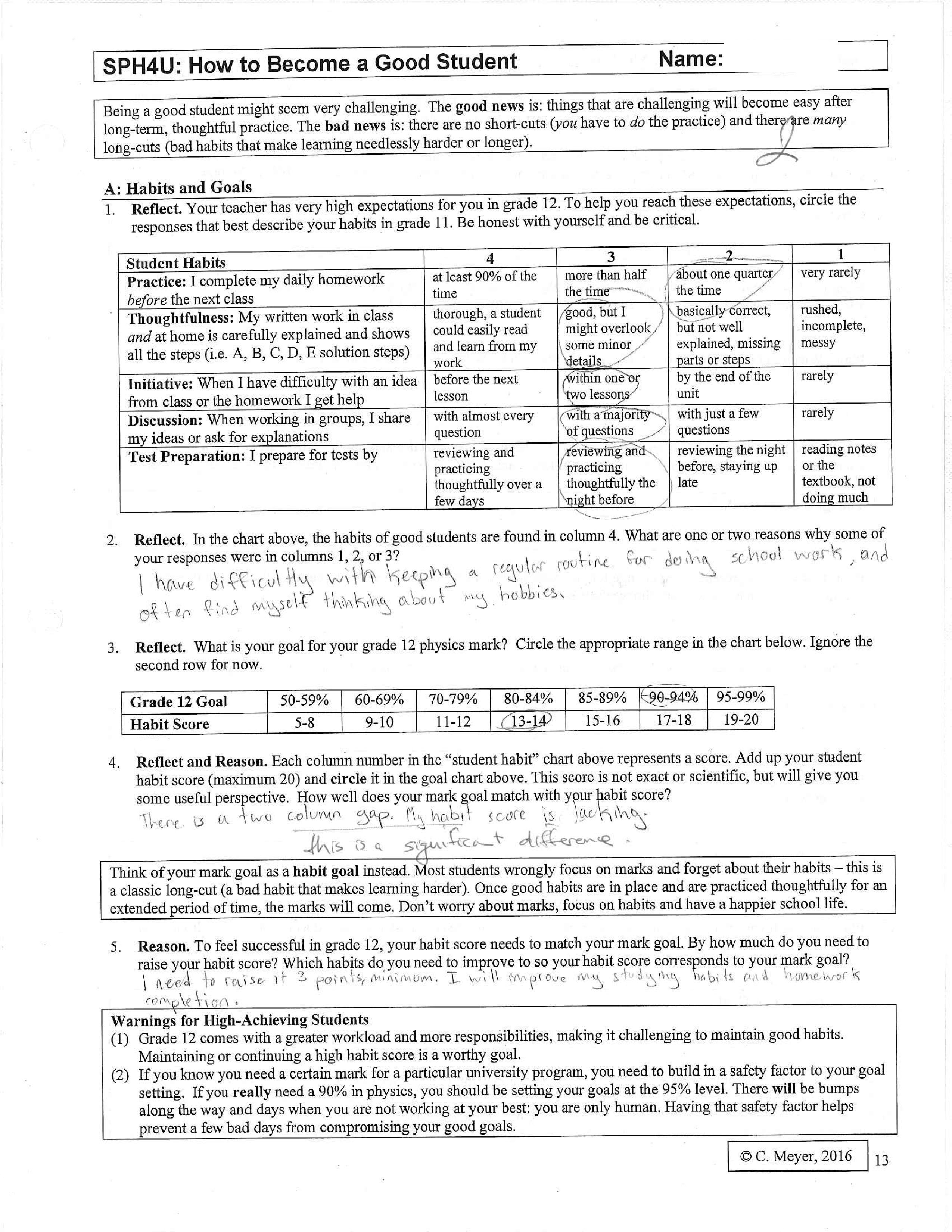

My recent (and first) attempt to train students starts with self-evaluation. They need to evaluate their own learning habits and “measure” how well those habits match up to their mark goals. To do this, I gave my students a homework sheet that asks them to reflect on a variety of skills and habits that I think are important for success in grade 12 physics. This helps to make the goal mismatch visible to students. A sheet completed by one of my students is provided below.

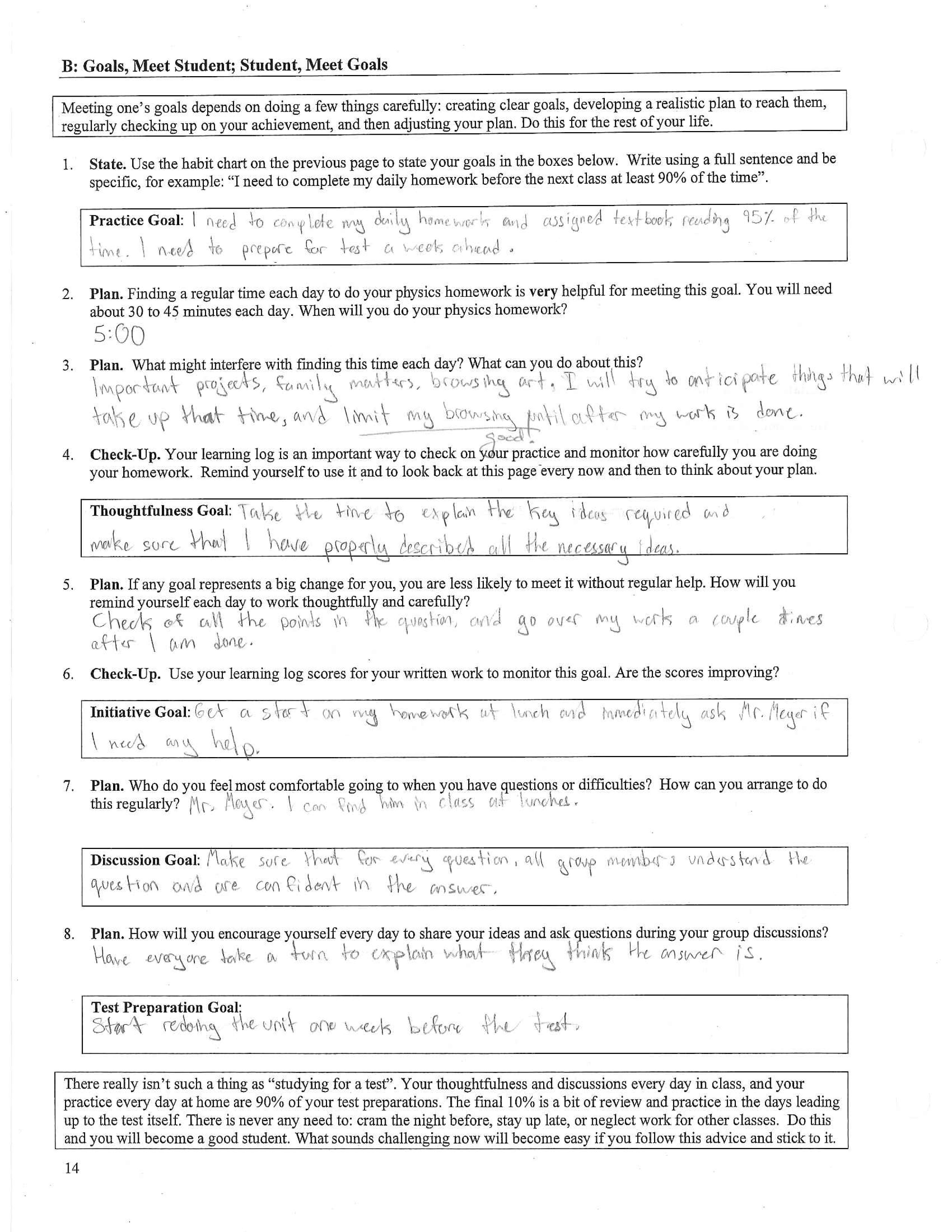

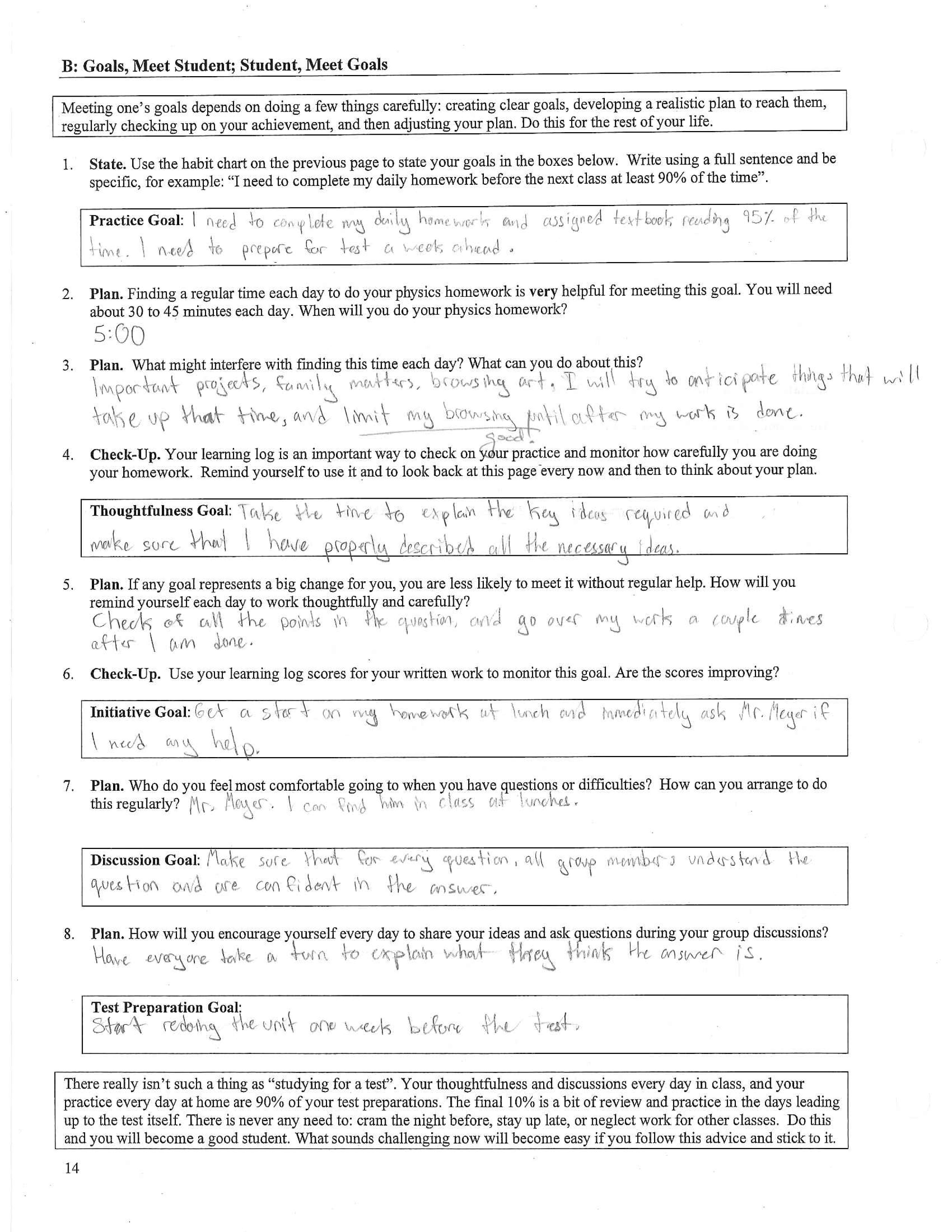

The next step is one that get to the heart of the problem. Mark goals are nice and all, but a mark goal needs to be “translated” into a learning habit goal, a skill-based goal. This focuses students’ attention on the concrete things they can do each and every day in order to attain their goals. An improved mark should be thought of as the happy by-product of improved learning habits. This change in emphasis can seem trivial, but it is profound. A focus on process over the end product allows students to take ownership of the problem rather than feeling like a victim of the next test. It can help alleviate the anxiety and pressure that comes from an exclusive focus on marks. Their attention can return to what they are learning and how their understanding can improve. Most importantly, this gives them the best real chance of improving their mark, rather than some misplaced hope in just “working harder”, whatever that means.

The sample above shows a student with high expectations and lower habits. It is likely they have never thought about marks this way (as a level of habits and skills), instead thinking of marks as a mystical achievement that some lucky students can conjure. The chart and scoring system I have come up with is hardly scientific, but I did calibrate it and adjust it after trying it with one class of students and it seems to be about right for my classroom (it is now slightly different from this sample, the revised version is attached here). Once students recognize that there is a “skill gap”, they need to learn how to improve those skills.

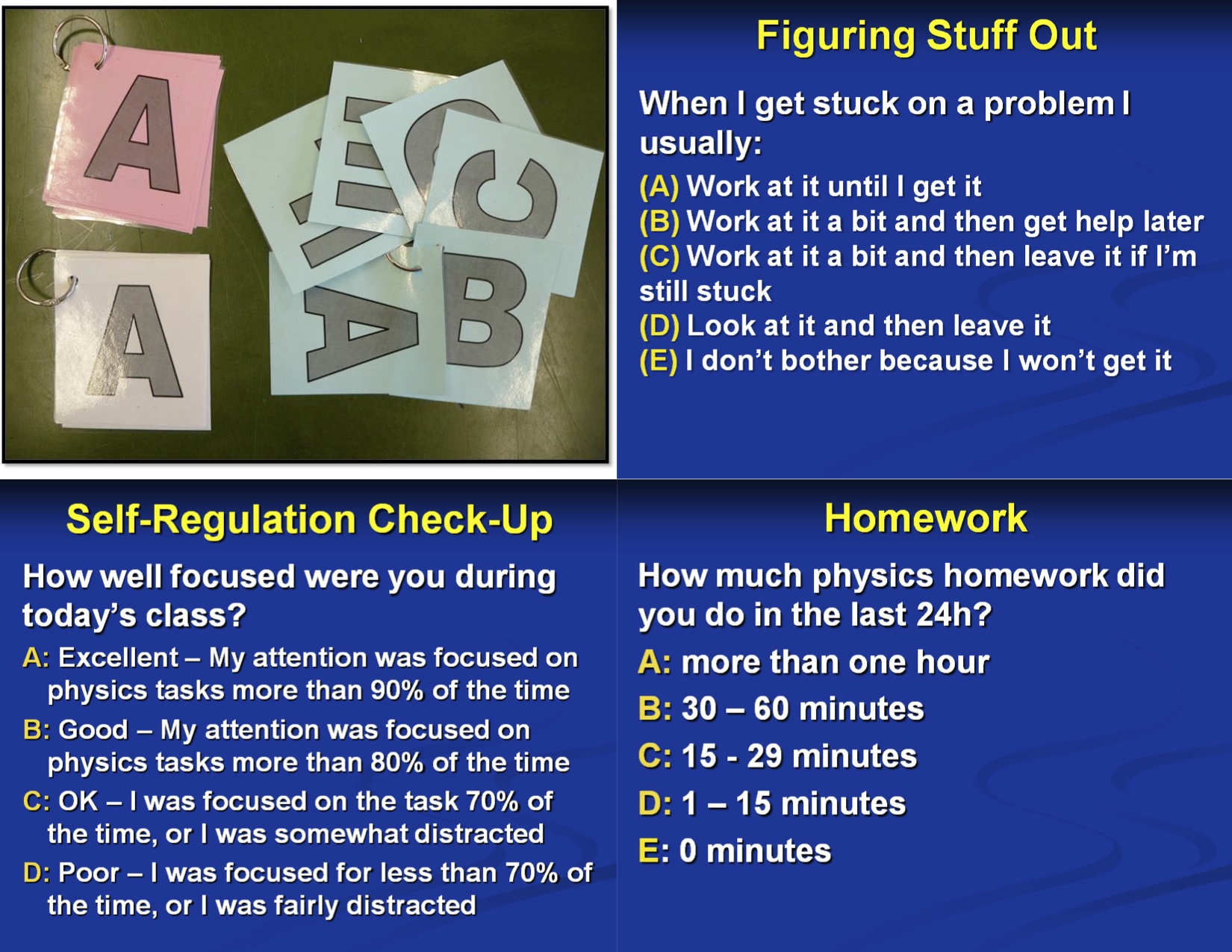

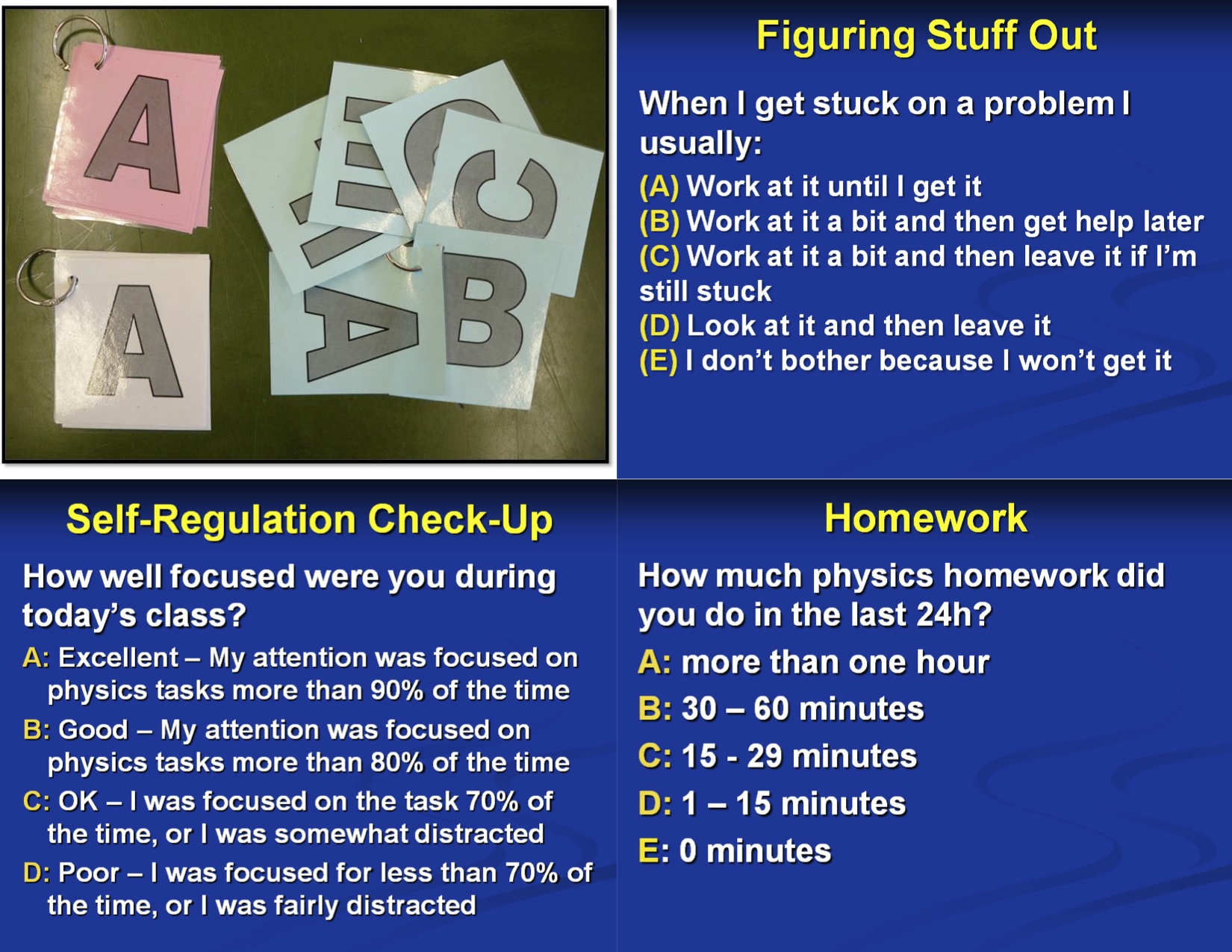

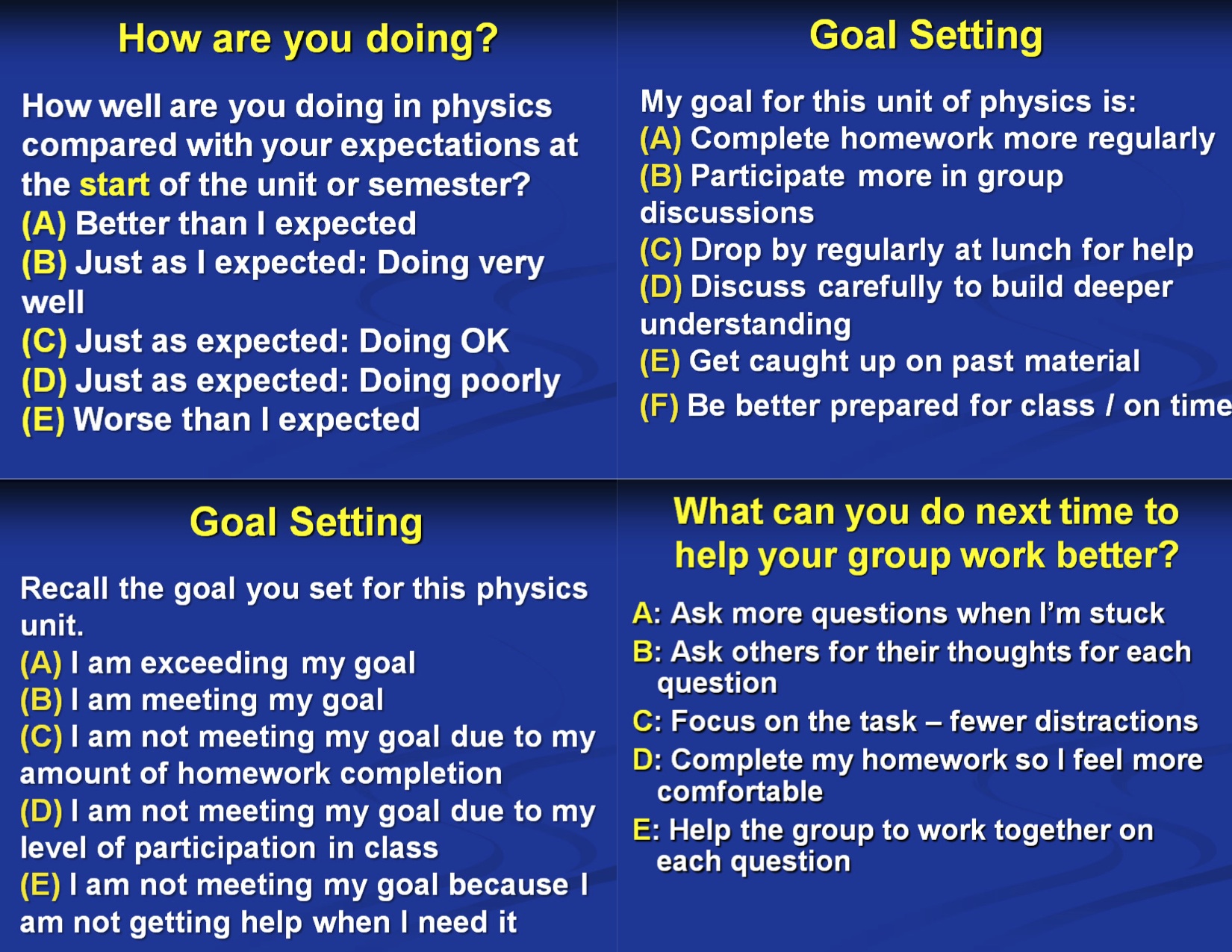

Achieving goals is a long-term process, and a long-lasting commitment is needed to make genuine improvement possible. The improvement of learning habits is hard work, but becomes easier after consistent, thoughtful practice. This is valuable to reflect upon: consider all the tough things we initially struggled with, but can now perform fluently at a subconscious level (walking, talking, adding single digits, patting the head while rubbing the tummy). All of these skills required sustained efforts over a long period of time, and persistence through many failures, to reach your level of mastery. Students don’t see this when we demonstrate our fluent skills for them, or when they observe them in their capable peers. That is also why I emphasize that there are no short-cuts: if students are not personally doing the work and practice, their skills won’t improve (watching others is not the best way to train for a marathon). But there are many long-cuts: all those counterproductive habits that students persist in, unless they are carefully trained out of them. To help students monitor their learning process and work habits, I regularly use multiple choice questions in class with the response cards each group has at their table. Here are some questions I use to focus students’ attention on their level of effort:

To reliably meet any goal, students need to clearly identify the goal, develop a plan, monitor their progress, and revise their plan based on their progress. The next page of the written exercise helps students to do this. In the future, I think I will use this self-evaluation worksheet twice a semester, near the beginning and again near the middle, which I will collect just before parent-teacher interviews…

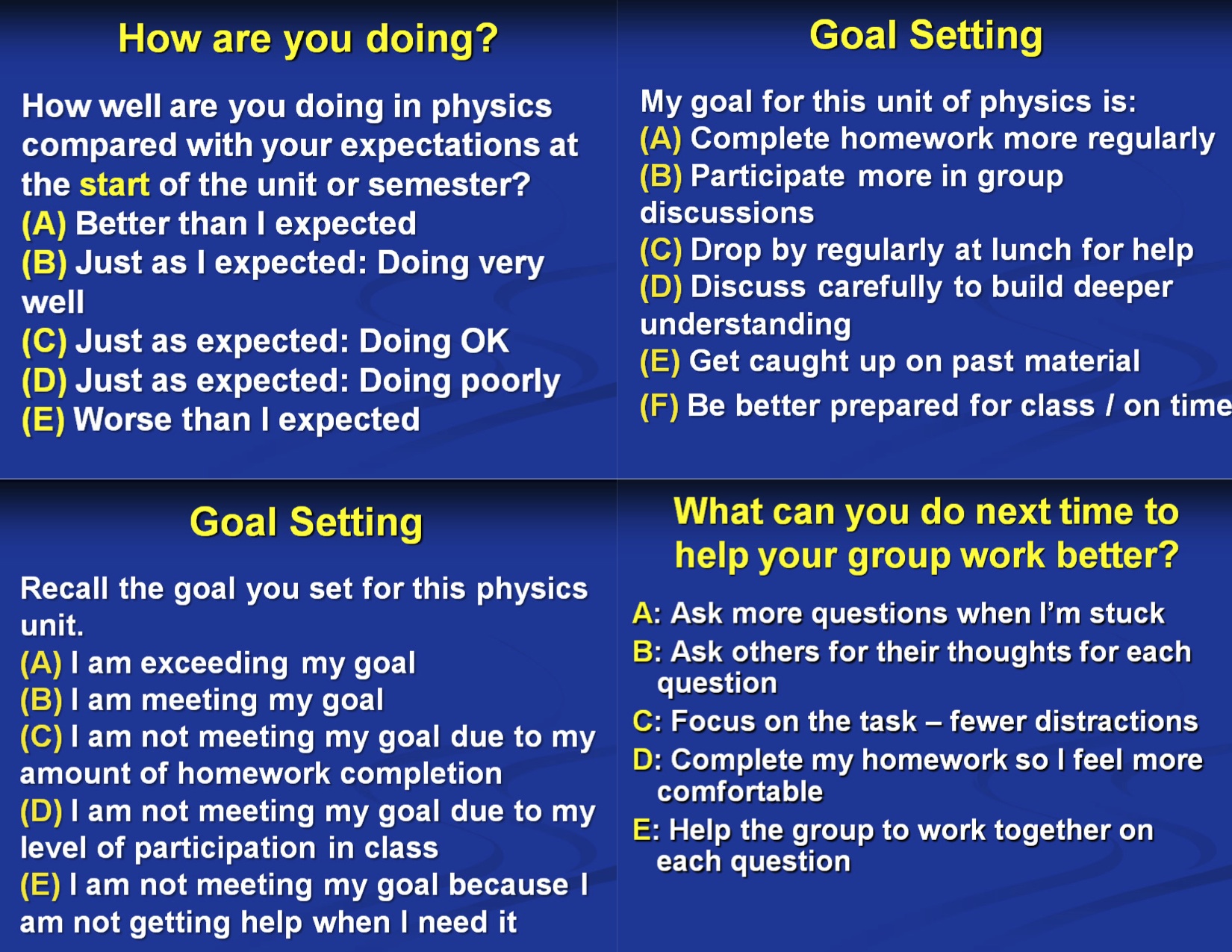

Students are much less likely to reach their various goals if they are not regularly thinking about them and monitoring their progress. I use some multiple choice questions in class to help students with this.

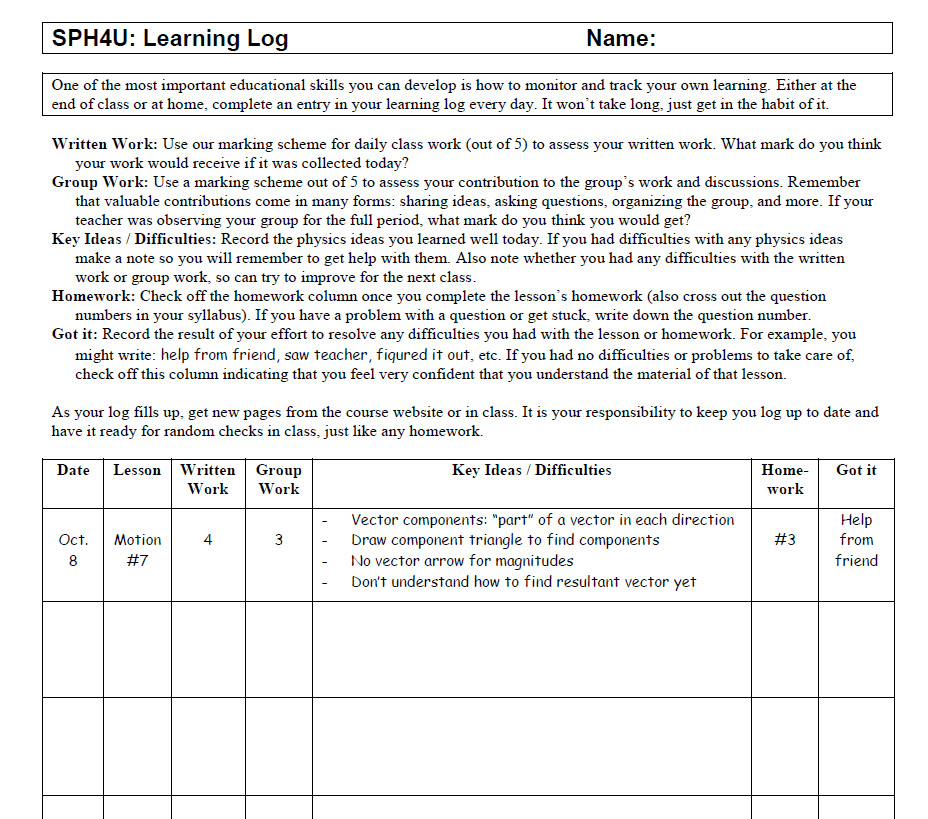

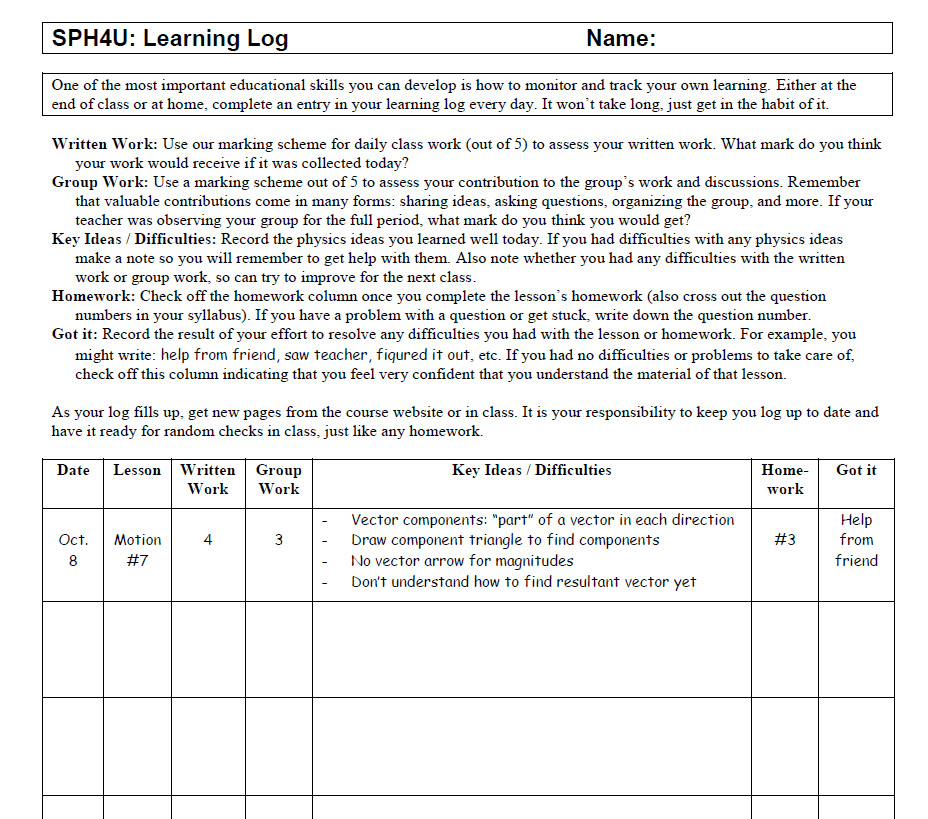

This all part of a package of skills called metacognition: understanding how one learns, and monitoring and adjusting one’s learning process. These are the skills that “life-long learners” have developed in spades. How often do we have our students consciously practice these skills? If our education system manages to produce a “life-long learner”, it is likely by accident. To help my students monitor their daily efforts, we use a learning log. Students evaluate their daily written work and group discussions, they record the day’s new ideas and any difficulties they have had, they note any homework questions they have not completed and whether they have found help for them. When students select a goal from the PowerPoint slides shown above, I often ask them to record it, using large print, on one line of the learning log so they see it each day.

And here is the moral of the story for us teachers: The longer I have been teaching (18 years now), the more strongly I believe that I am not a physics teacher, but a skills teacher. My job is to help students learn productive behaviours and eliminate harmful ones. We happen to learn physics along the way, which is fun, but my main task is to train young people to become good students. To do this, as a profession we need to explicitly train students in the desirable habits and give them opportunities to practice those habits, with feedback. We can’t rely on students picking them up along the way. The “sink or swim” model of education is very wasteful of everyone’s time and energy. The vast majority of students can do really, really, well. We just need to train them as if they will.

Resources:

Tags: Assessment, Pedagogy