Felipe Almeida, Toronto District School Board

felipe.almeida@tdsb.on.caAs every student in an introductory physics course (like SPH3U, the grade 11 physics course in Ontario) is untrained, all their practice should be portioned appropriately in both task and problem. I have created scaffolded practice problems for the grade 11 physics course in Google Forms so students can submit their responses for immediate feedback. The forms are intended to save time and make practice/‘homework’ more meaningful and rewarding for both teachers and students. A

previous article presented the forms used for portioned practice, this article will present fast feedback.

Fantasy Second Career

This year has been a tough one. I wonder, have you given much thought as to what your fantasy second career would be? For me, easily, it's stand-up comedian.

The Stand-Up

The Stand-Up

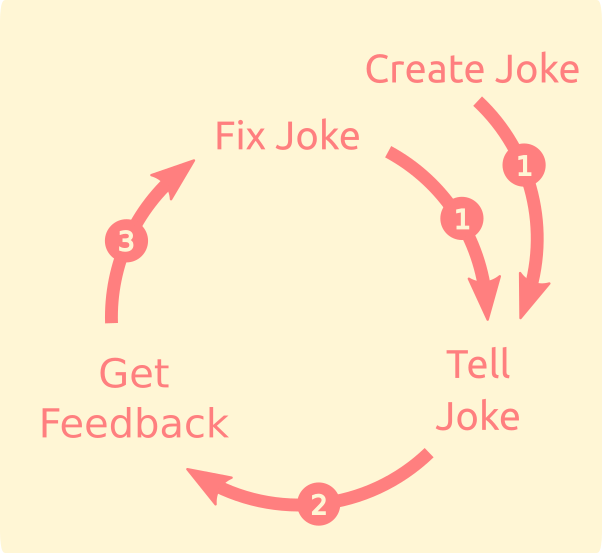

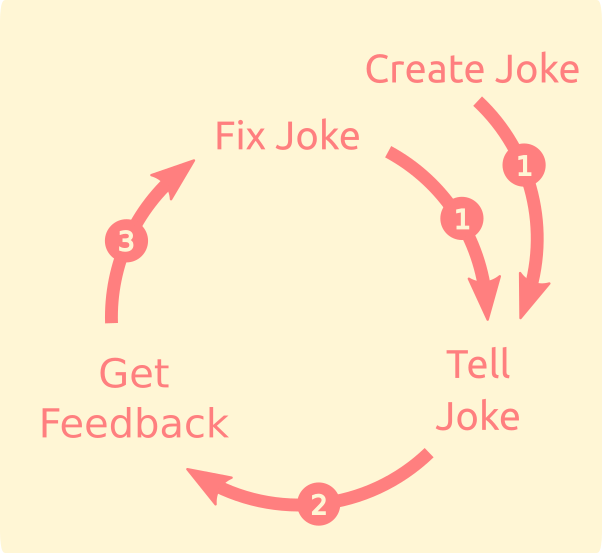

Making people laugh, bringing joy to the world... sounds like a pretty good way to make a living. I like challenges, and standing up in front of an audience of strangers and engaging them for any significant amount of time is extremely difficult to do. But, the real draw to being a stand-up is that I can’t think of another profession with a better mechanism for feedback.

You get up on stage and say something you think is funny

1, and immediately you know to what degree you are successful. If the audience laughs, you know you're onto something. If nobody laughs, and you can accept that horrible sound of silence that follows

2, you reflect, modify, and try again. Still nobody laughing? Keep reflecting, modifying and trying again, and eventually you get better and better.

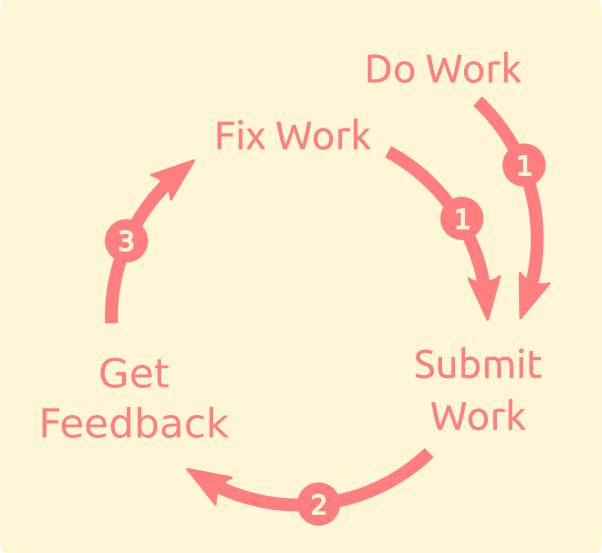

The iterative cycle of becoming funny

The iterative cycle of becoming funny

In other words, I can’t think of another environment better suited to learning and risk-taking.

Automated Feedback

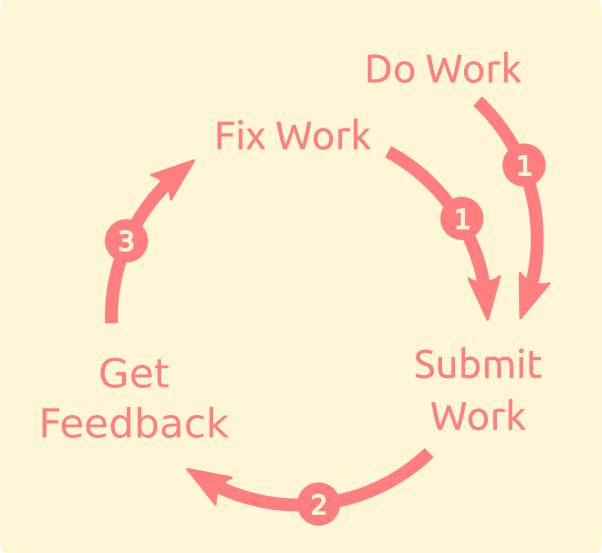

Ok, enough fantasizing. I'm not going to give up my regular job! In fact, when hearing the words 'learning and risk-taking', I immediately think of my students and what can be done to help them do more of it. But they don't want to be funny, they want to be educated, so their efforts should look like the following:

The iterative cycle of becoming educated

The iterative cycle of becoming educated

The quicker and smoother transitions

①,

② and

③, the closer students get to an ideal environment for learning and risk-taking. Can they be optimized?

As teachers, we can provide students with structure and encouragement towards the expedient completion of transition

③, but transition

② is where we reach our limits. The quality and detail of our feedback is high, but if not delivered immediately, it quickly loses its value. Maybe if our classes consisted of a single student could turnaround times be sufficiently short, but even then, the time at which a student does work does not always overlap with the time when we are available (e.g. I'm fast asleep at 2:00 AM).

An equivalent kind of feedback as immediate as the stand-up's is not going to come from us, despite our best intentions

An equivalent kind of feedback as immediate as the stand-up's is not going to come from us, despite our best intentions

The only way to optimize transition

②, then, is to automate it. If a computer is now going to provide students with feedback, it will need help interpreting their work. This means we need to think creatively about how to do transition

①.Google Forms with Portioned Practice

One way of optimizing transitions

① and

② is by combining the auto-correction abilities of Google Forms with the portioned practice described in my

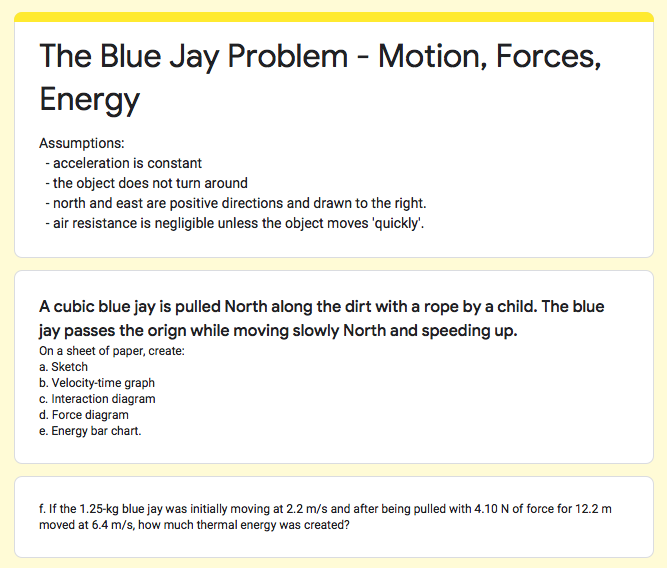

previous article. To get a sense for how it can work, below is an example involving the motion of a blue jay with tasks sampled from the grade 11 Motion, Forces and Energy units. The form is set to:

- collect email addresses — to know who submitted the form

- return results (but not answers) immediately — for the submitter to know what was done correctly and what wasn't

- allow an unlimited number of edits — so the submitter can keep working until 100% correct

(*Feel free to submit responses.)

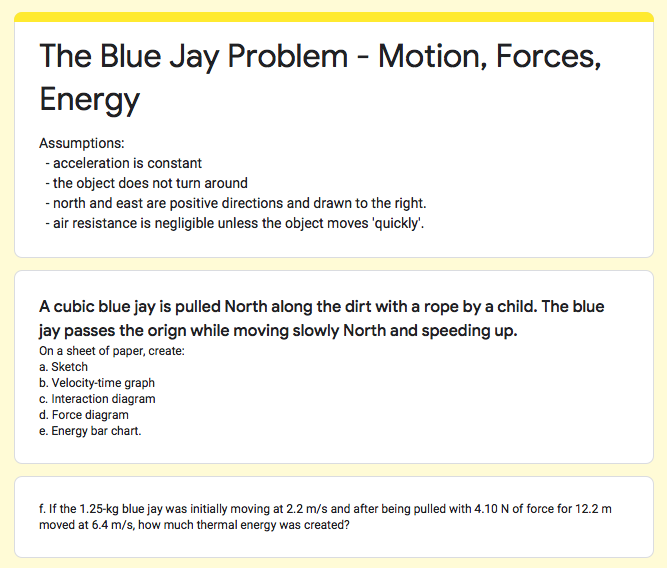

Sampling of tasks from several grade 11 forms — click on the image to try them out!

Sampling of tasks from several grade 11 forms — click on the image to try them out!

Several forms with portioned practice (and the same setup as above) for motion, forces and energy were created and used at the TDSB's Virtual Secondary School during quads 1 and 2 (2020-2021). They can be found

here, and immediate access to make copies and edit your own

here.

Benefits, Drawbacks (Quads 1&2, 2020-2021)

Benefits

- Increased engagement

Though lacking a historical baseline of practice/homework completion to compare to, with these forms, I know that a lot of students did their work, and often 100% complete.

- Students can choose feedback timing, amount

Students can get feedback one entry at a time, or as they grow in confidence, a whole problem, or even a whole form at a time. The choice is theirs.

- “We have a sense of which areas we need more work on.” — student quote.

- “I enjoy… being able to keep trying until I get them correct.” — student quote.

- Participation of the clueless, identification of the clueless

In the sample form above, for example, there are 14 possible sketches to choose from, and a student could try every option until they get it correct. The students who do this are usually the ones who have no clue what they are doing, but by submitting, they are still participating and getting feedback as opposed to silently checking-out and quickly falling further behind. Certainly, you wouldn't want this practice to continue, and if you're tracking the number of form edits (see Submissions vs Edits, below), you can immediately identify who these students are and provide support.

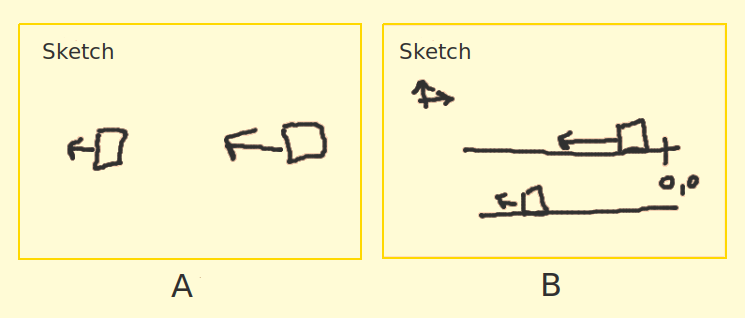

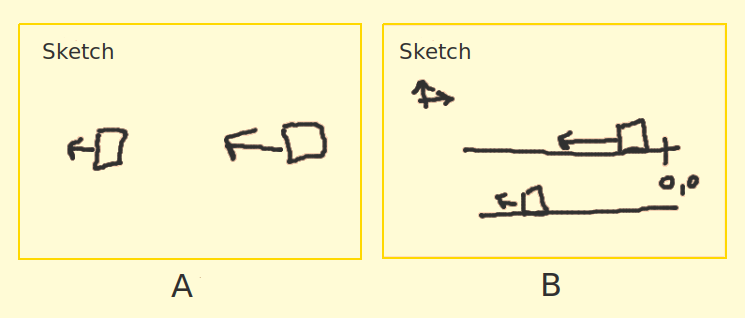

- Improved work on paper

On evaluations where students submitted their work on paper, a lot less of it resembled example A and more of it resembled example B (B reflects the answer keys from the practice forms).

Submitted work on paper matches the quality of answer keys, as shown in B.

- Forms resolve many questions that don’t require a lot of expertise to address, freeing up valuable teacher time

Time previously spent on trivial errors can instead be used to provide students with social and emotional support (requiring your expertise as an educator), and the academic questions you do get are usually higher-order (also requiring your expertise as an educator).

Drawbacks

- Feedback is binary, not descriptive

Students only find out (in most cases) if their responses are correct or not and sometimes can’t identify the sources of their errors. In such cases, they have to contact you directly (which suddenly feels anachronistic, for better or worse).

- Forms can be cumbersome

To ensure the value of form feedback exceeds the effort to make a submission, the amount and type / diversity of tasks in the forms need to be considered carefully.

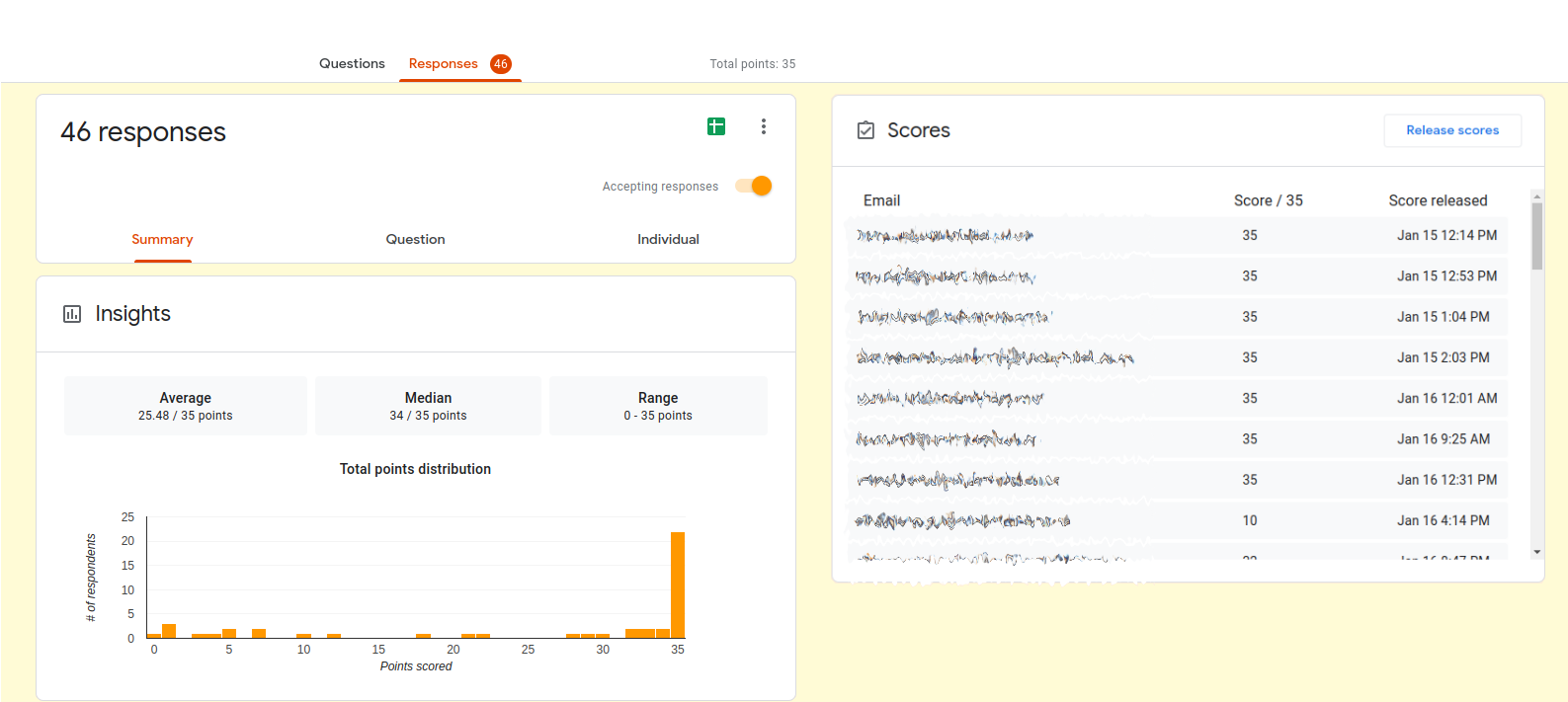

Feedback for Teachers

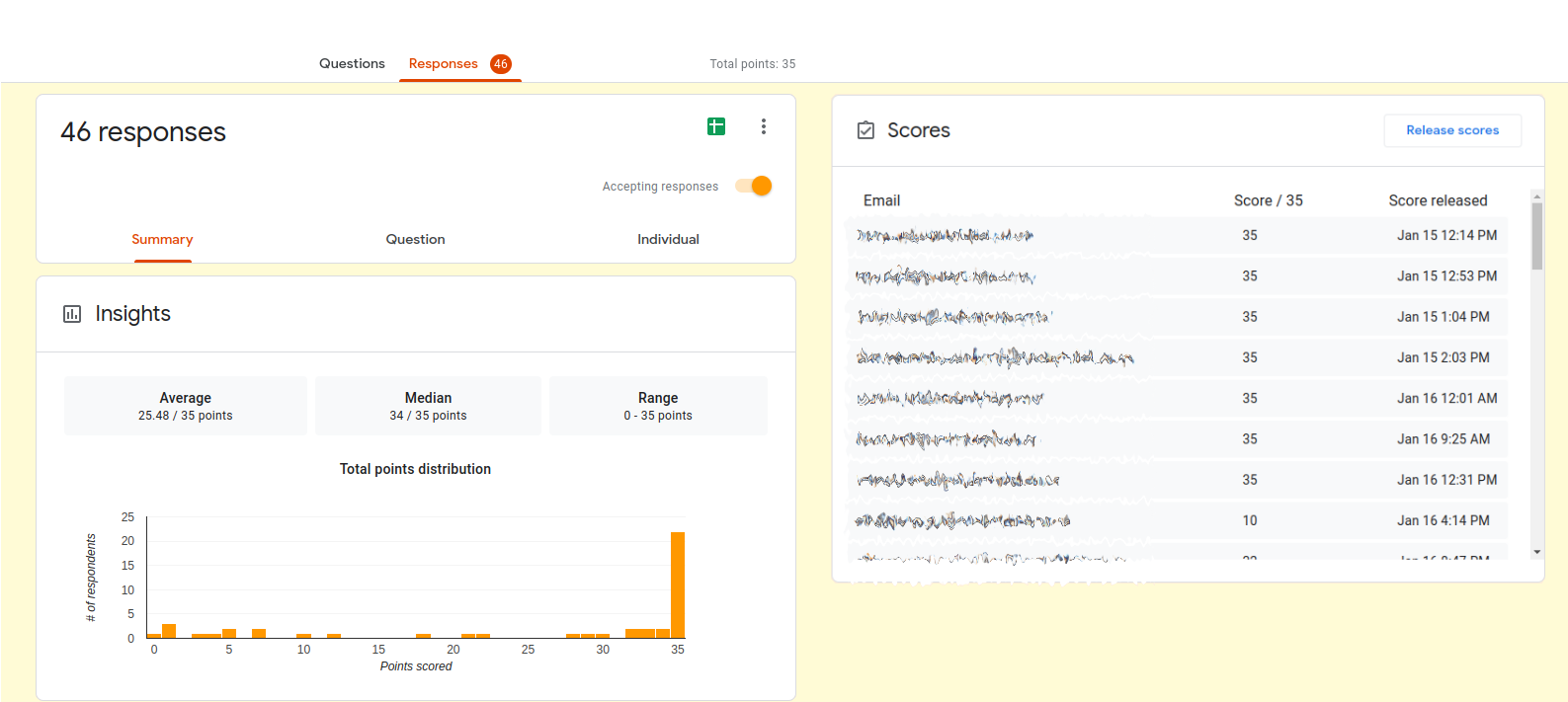

In the 'Responses' tab, the forms provide a significant amount of information about student submissions, including total score, score for each task, and a timestamp. There is also a summary of all the submissions made by the entire class.

Sample of default information on form submissions

Sample of default information on form submissions

However, there's a bit of a quirk to google forms that complicates things a little...

Submissions vs Edits

The forms are set to accept only one submission per student, but the submission can be edited any number of times. Editing a submission allows students to change only what they got wrong (which they like), whereas making a new submission requires re-entering all their work all over again (which they do not like).

However, unlike submissions, the forms do not track the number of edits! Thankfully, we're not stuck with either frustrating our students with resubmissions or not knowing the number of edits they make (and losing the ability to identify the clueless). The solution, however, is not trivial and requires the use of Google Sheets and Google App Script. But once comfortable with sheets and app script, a whole world of possibilities open up...

Completion Data Summary

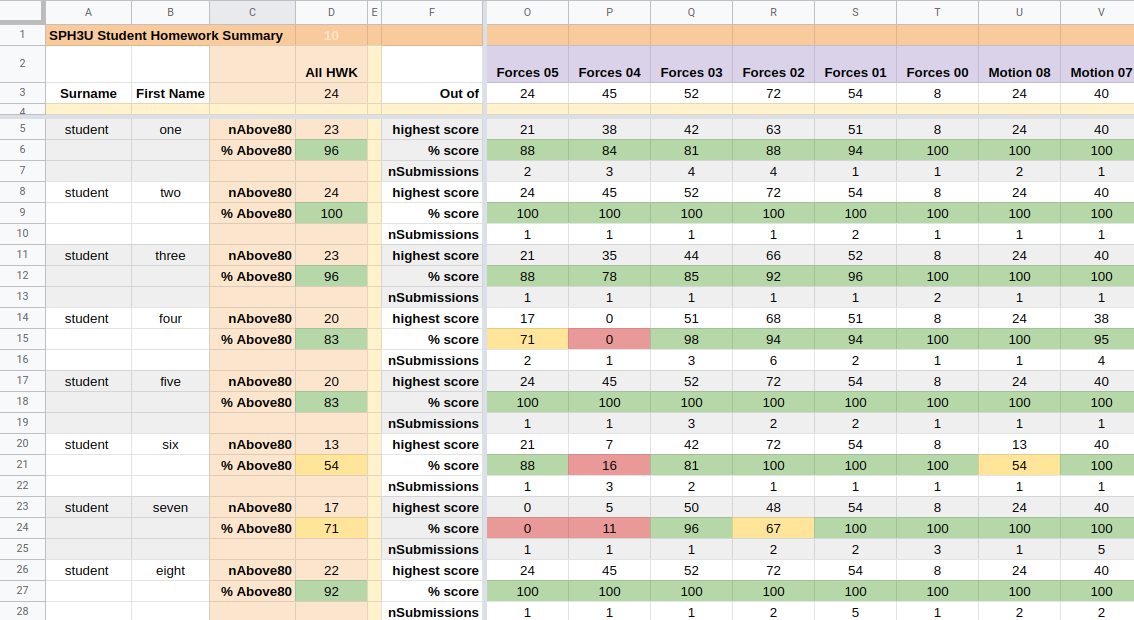

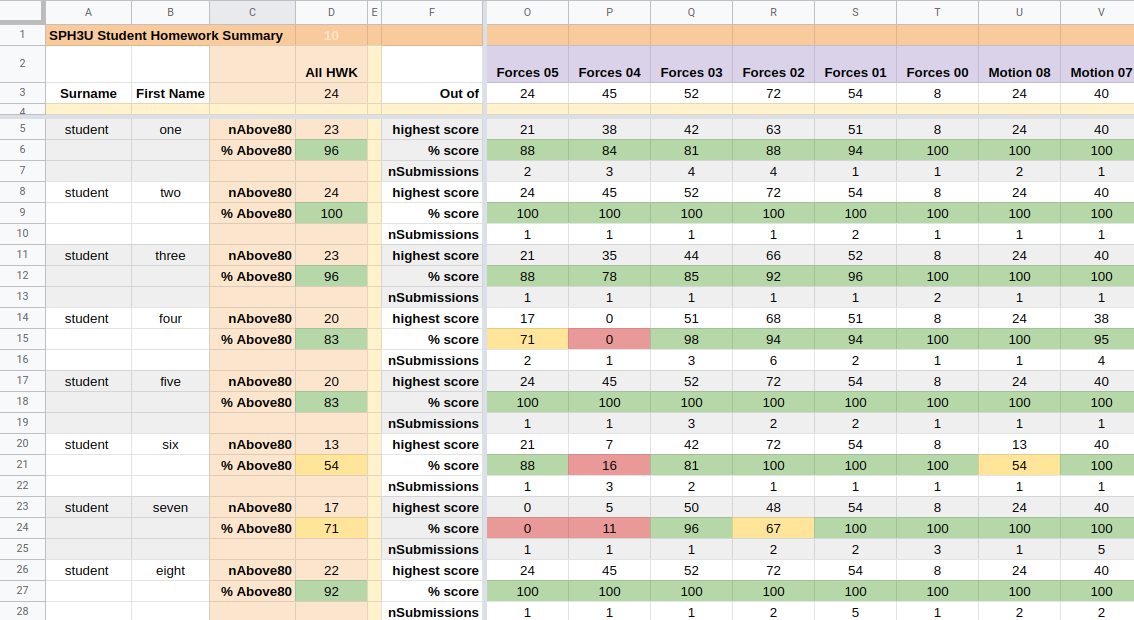

Summary of class form results from grade 11 physics, Quad 2 2020-2021, on a Google sheet. Student data is in rows, form data in columns. The left-most practice (Forces 05) is the most recent shown.

Summary of class form results from grade 11 physics, Quad 2 2020-2021, on a Google sheet. Student data is in rows, form data in columns. The left-most practice (Forces 05) is the most recent shown.

The spreadsheet above has been configured to collect the score and the number of edits

3 for all the forms in the course. Conditional formatting is set to show green for practice 80% complete or above, yellow for between 50% and 79%, and red for less than 50%.

All at once you can get a sense of how well each student is performing (by examining rows) as well as how well the class is doing on each form (by examining columns). You can also notice patterns that develop (e.g. student seven was consistently completing forms until the last two; this student warrants a check-in). This data can also be useful for students, parents / guardians, guidance counsellors, student success, vice-principals, etc. and easily shared at your discretion.

A blank completion data summary spreadsheet (and instructions) can be found

here (only a basic knowledge of sheets and no previous knowledge of app script are needed).

Future Plans

As educators, we want all our students to develop expertise in the content of our courses. According to Nobel economics laureate and psychologist Daniel Kahneman

4, to achieve that, students need:

- A regular environment (i.e. one with stable rules)

- (lots of) Practice

- Rapid feedback

High school physics content is stable and the forms promote practice and provide rapid feedback, so all conditions appear to be met. However, every student gets the same forms, meaning everyone gets the same amount and difficulty of practice (and one size does not fit all

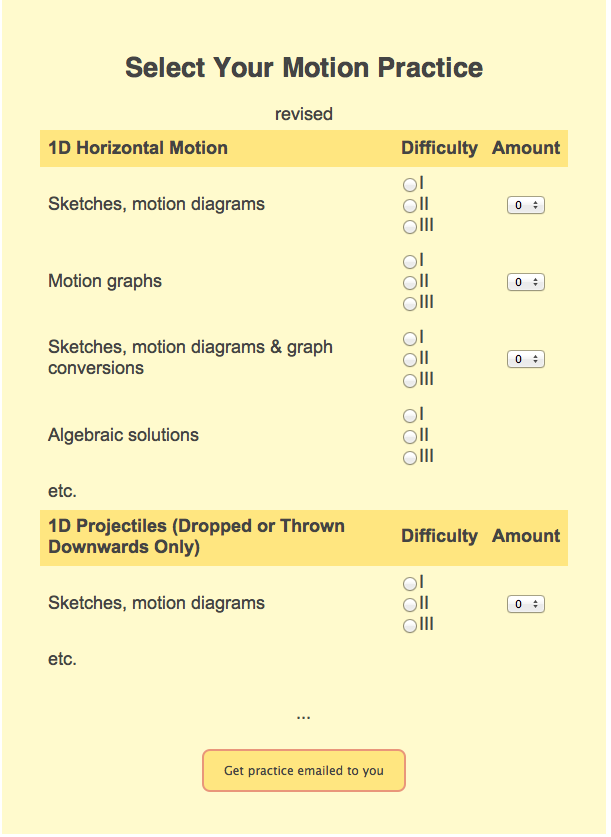

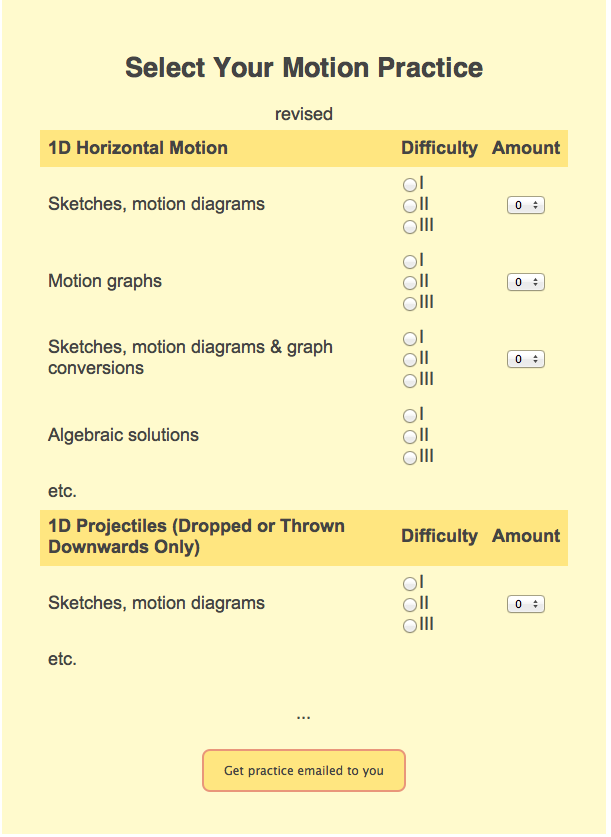

5). Imagine students only having to do as much practice as necessary to demonstrate expertise before moving on to something new, utilizing something like the following:

Students select the practice they need from an unlimited number of problems with varying difficulty. How much would this be appreciated by those who find class pacing too fast and those who find it too slow? (Don't most students in a class find the pacing either too fast and too slow?)

Students select the practice they need from an unlimited number of problems with varying difficulty. How much would this be appreciated by those who find class pacing too fast and those who find it too slow? (Don't most students in a class find the pacing either too fast and too slow?)

Assuming I can find the time to do so

6, future work would go into making a coherent system of forms with an unlimited supply of generated portioned problems

7. Regardless, hopefully in their current state, the forms can reduce some of the demands on your time while making your students' practice more meaningful and rewarding.

Use the Forms!

Forms for grade 11 motion, forces and energy can be found

here and get immediate access to make copies and edit your own

here. The spreadsheet (with instructions) that summarizes student submissions can be found

here.

Editor’s Note: The information in this article was presented at the OAPT Physics Hour on March 4, 2021.

Notes

- Part of the fantasy is me actually having funny things to say.

- That is, have a growth mindset.

- I switched from allowing multiple submissions to only allowing edits during quad 2, and the functionality for counting edits came at the end of quad 2, so the spreadsheet shown didn't accurately count edits. However, the new template does.

- Daniel Kahneman — The Ingredients for Expert Intuition

- Here I am referring to the idea of 'flow' as described by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (see Flow, the Secret of Happiness).

We want our students to be in flow (as do they themselves), but any given task will appear in different locations in the challenge level-skill level plane for every student, hence the need for many questions at different difficulty levels.

- Anyone have ideas as to how to get the time/funding to get large, non-trivial resources like this done? Let me know! (felipe.almeida@tdsb.on.ca)

- Portioned Practice and Fast Feedback actually began with the idea of creating unique practice problems for every student in a class. 10 problems for a class of 30 students is 300 unique problems - clearly these would have to be generated, along with their answer keys. This was what initially got me thinking about how to structure problems such that their responses can be checked by a computer. Feb 2020's initial attempt with 1D motion was successful enough to try again, but then schools closed in March and efforts went into pivoting to remote learning (where I first started using Google forms). In virtual school in the fall, the generating part was dropped (I didn't have time to make it work with forms) but returned later for evaluations after the discovery of significant academic dishonesty. The point is, generating unlimited problems is possible and has been done, but is not currently integrated with the forms.

Tags: Pedagogy, Remote Learning, Technology