Robert Prior, ePublisher of OAPT Newsletter

science@robertprior.caThe new artificial intelligence chatbot ChatGPT, from OpenAI, has been in the news lately, with many pearls clutched about the possibilities of students using it to cheat, while boosters have proclaimed that it is poised to revolutionize teaching.

I’ve spent some time playing with it, and at the moment it doesn’t match the hyperbole of either side.

What is ChatGPT?

ChatGPT is a chatbot: software designed to be able to hold a conversation. It

is a huge advance on

ELIZA, but Elon Musk’s assertion that "ChatGPT is scary good. We are not far from dangerously strong AI.” seems more Muskian hyperbole or trolling than an actual reasoned prediction.

ChatGPT is currently free for use, as it is in open beta testing. In the future it may become a paid service, like OpenAI’s DALL-E image generation system.

You can try it for yourself

here.

According to Sam Altman

According to Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, “Generative text is something we all need to adapt to. We adapted to calculators and changed what we tested for in math class, I imagine. This is a more extreme version of that, no doubt, but also the benefits of it are more extreme, as well.”

ChatGPT is often overloaded. About half the time when I tried to use it, especially during the day, I got a cute message telling me to try again later.

How does ChatGPT respond to short answer questions?

How does ChatGPT respond to short answer questions?

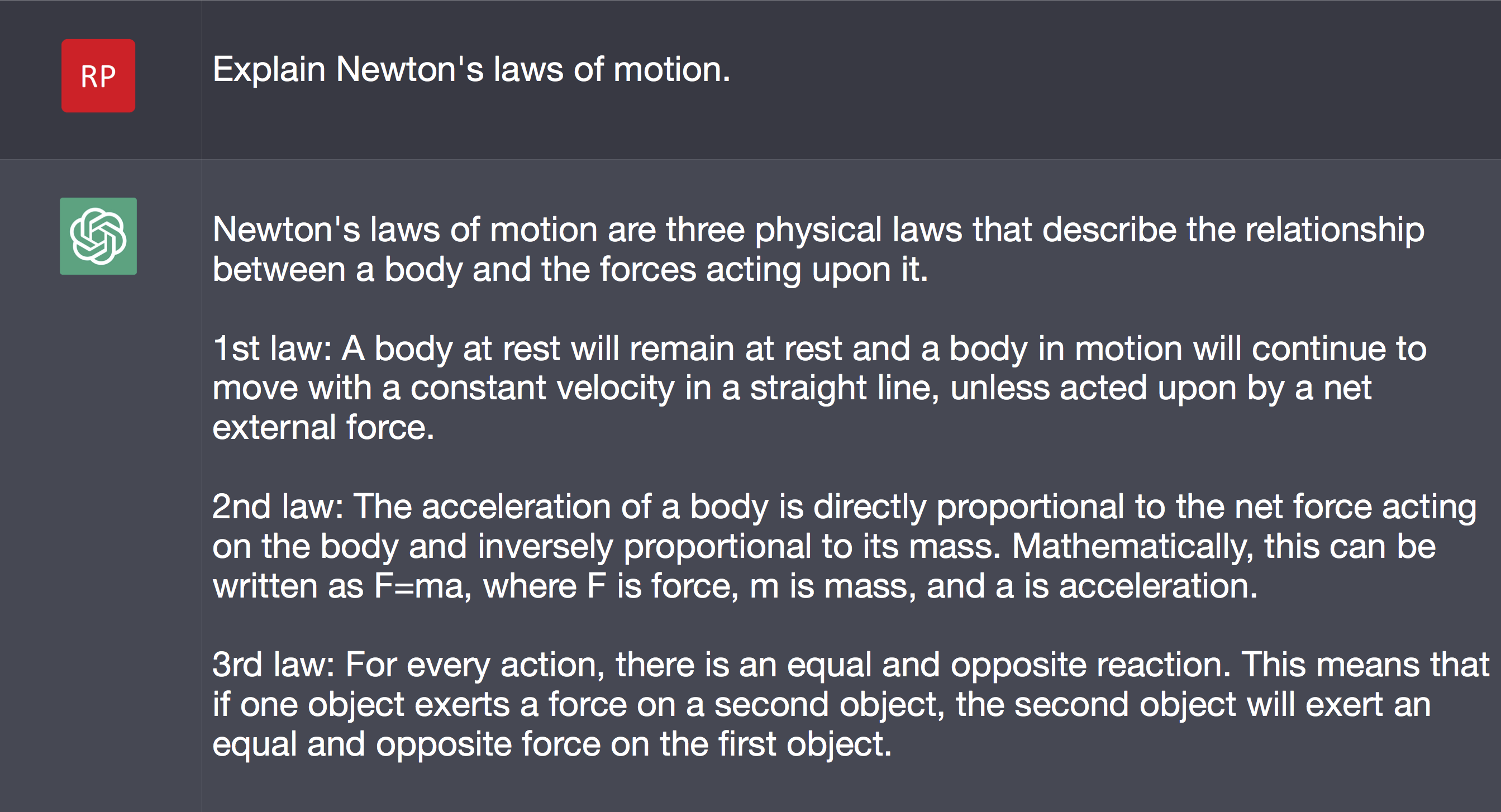

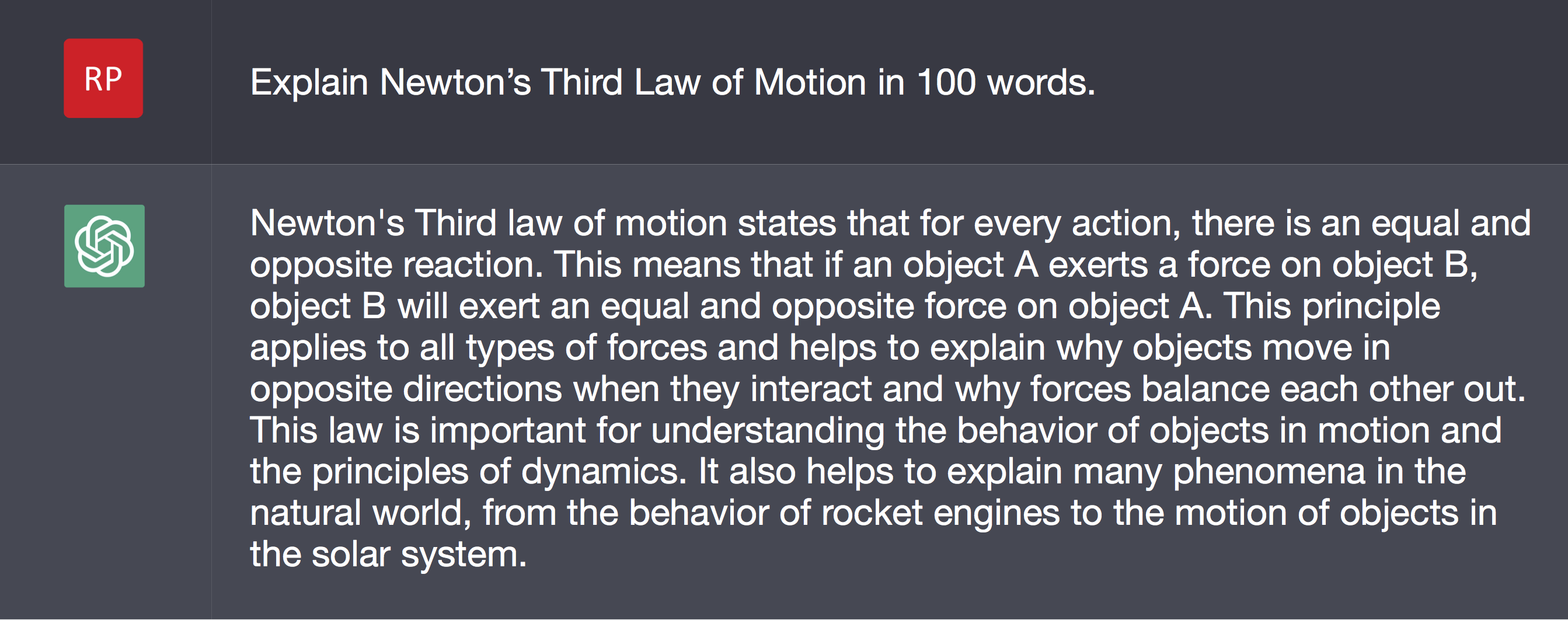

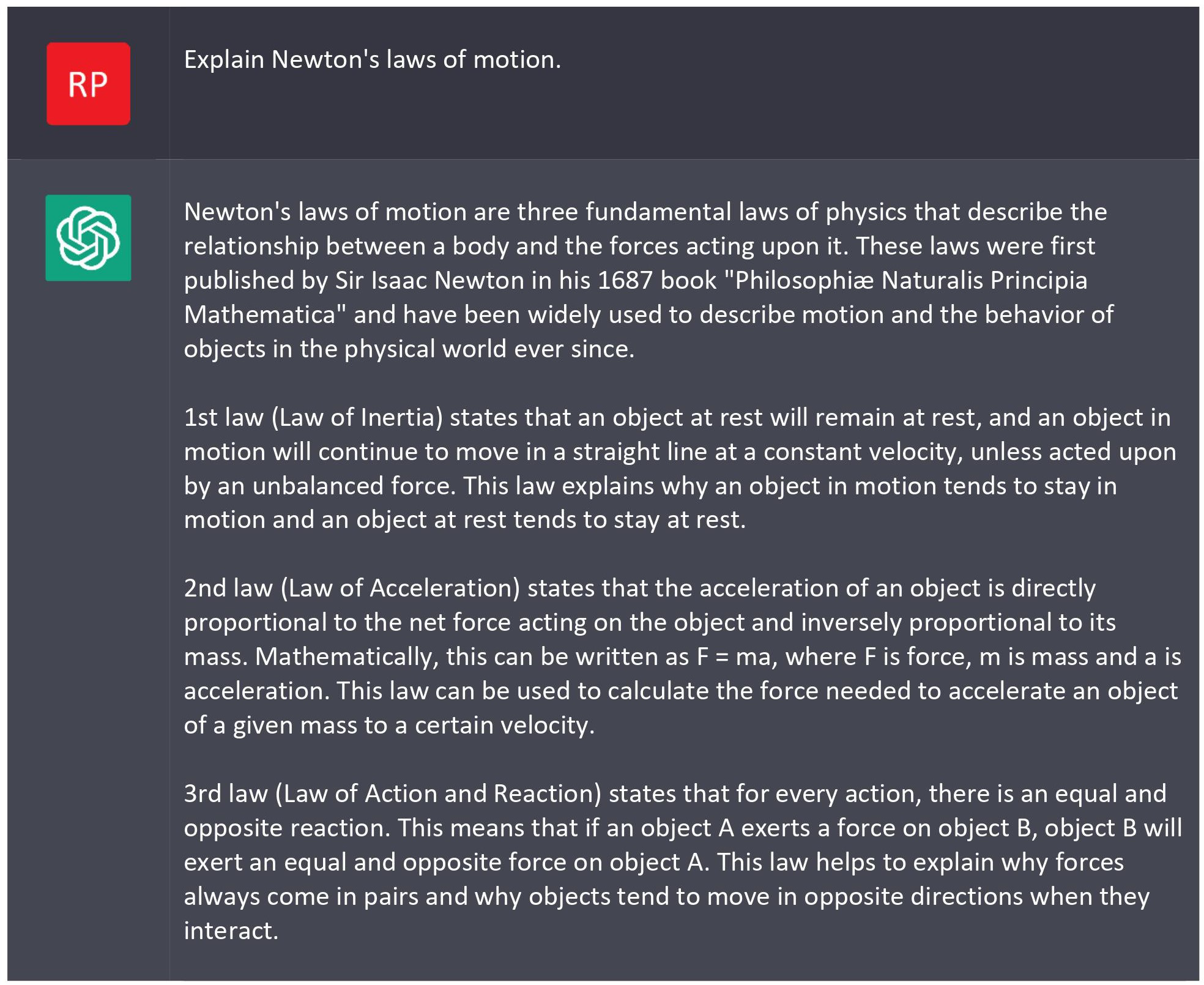

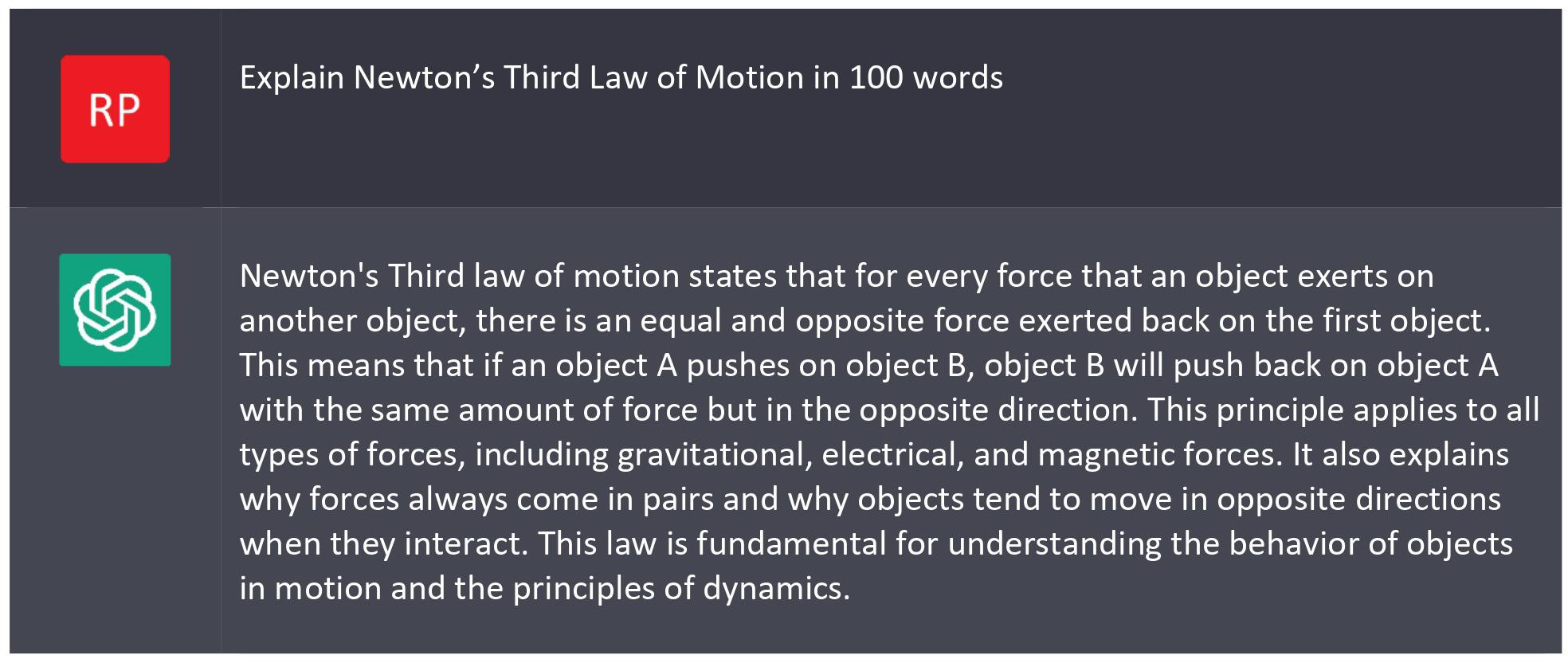

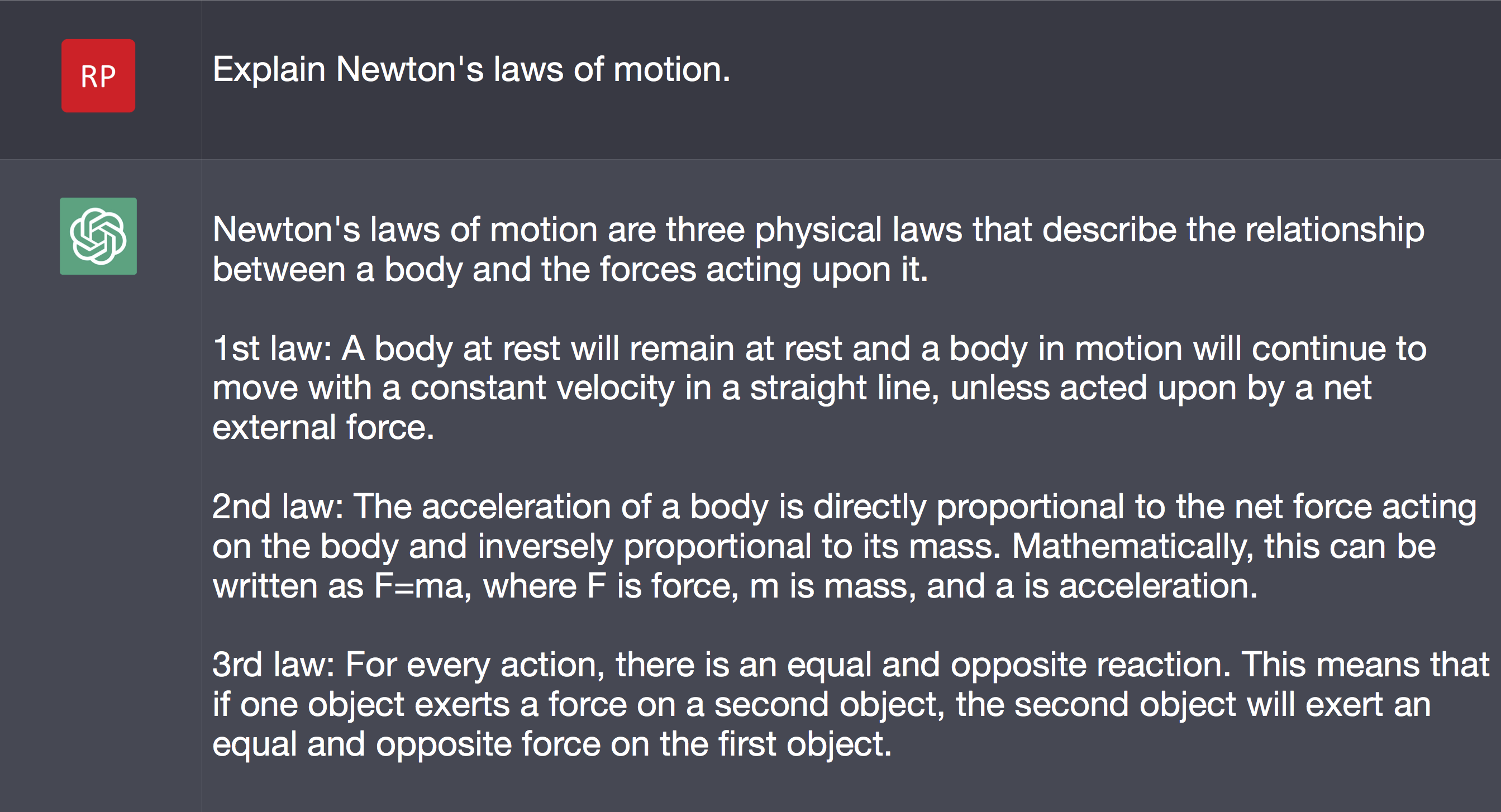

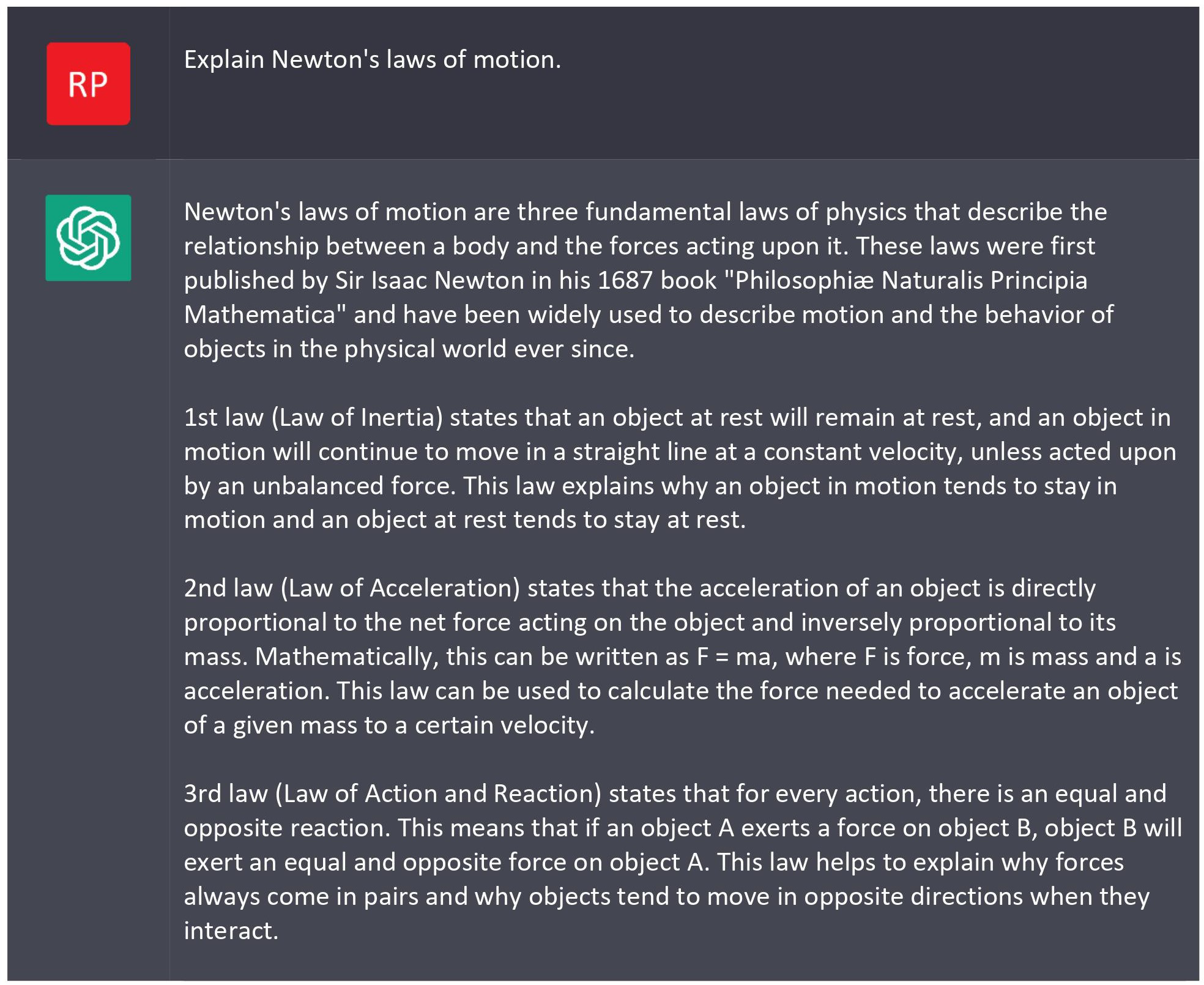

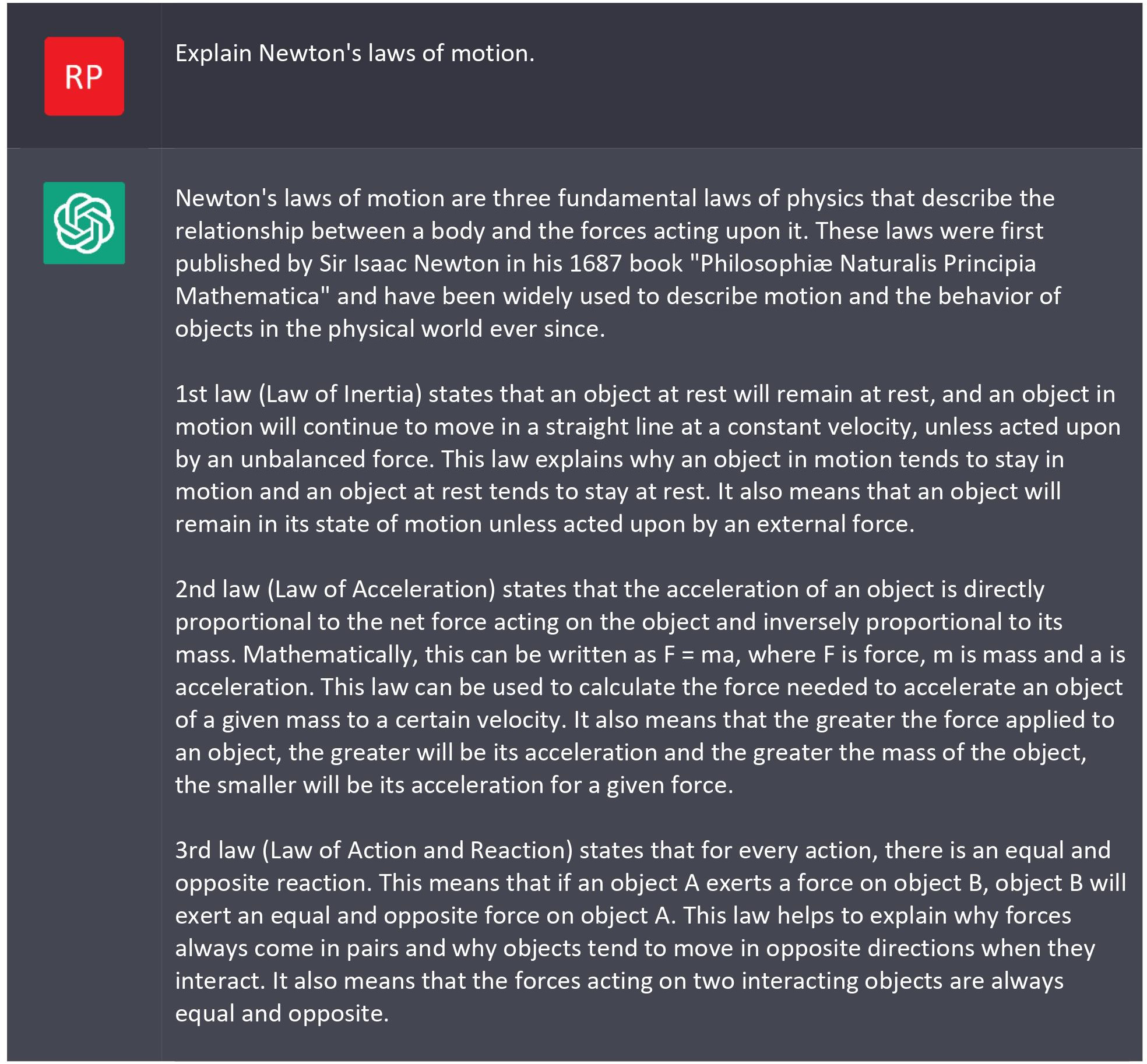

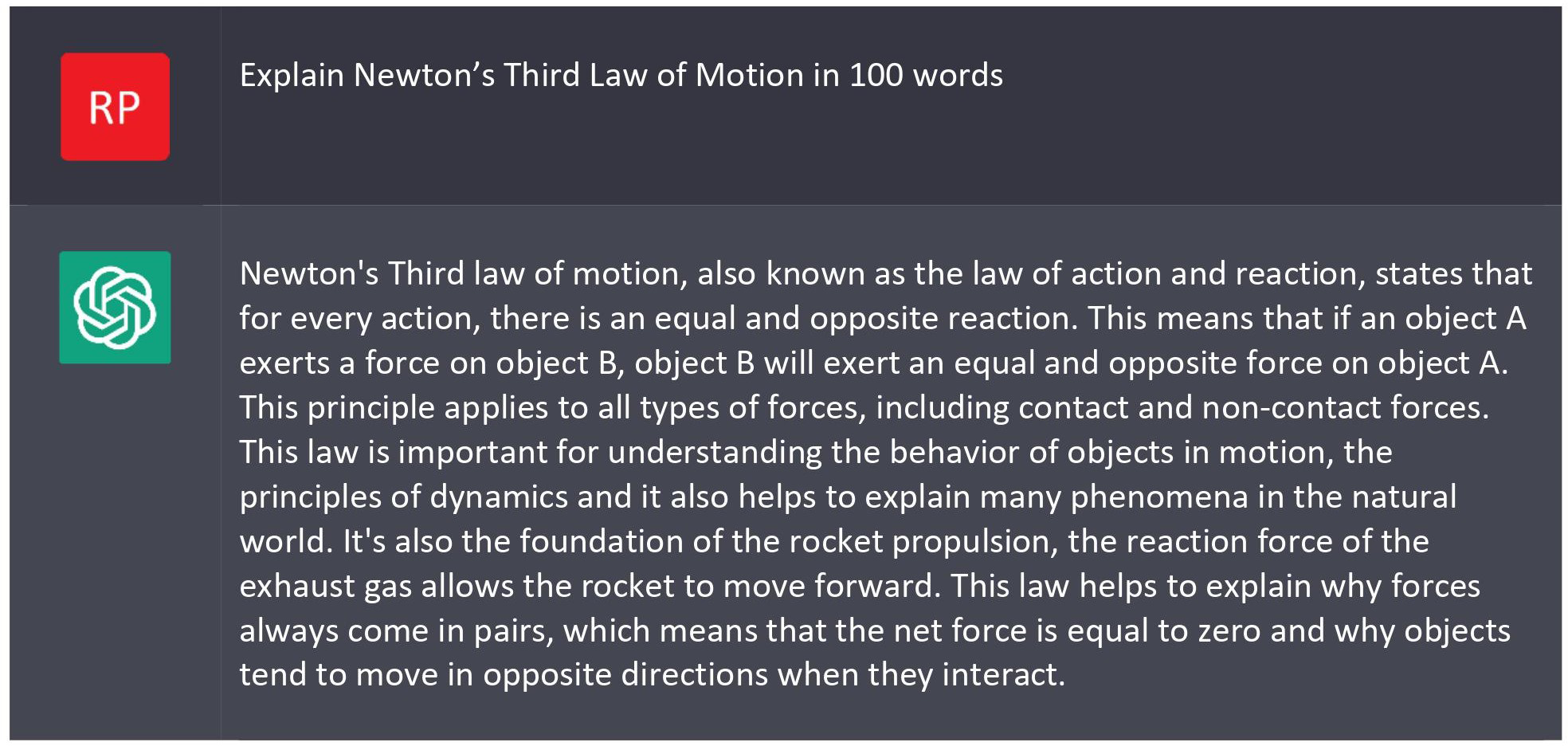

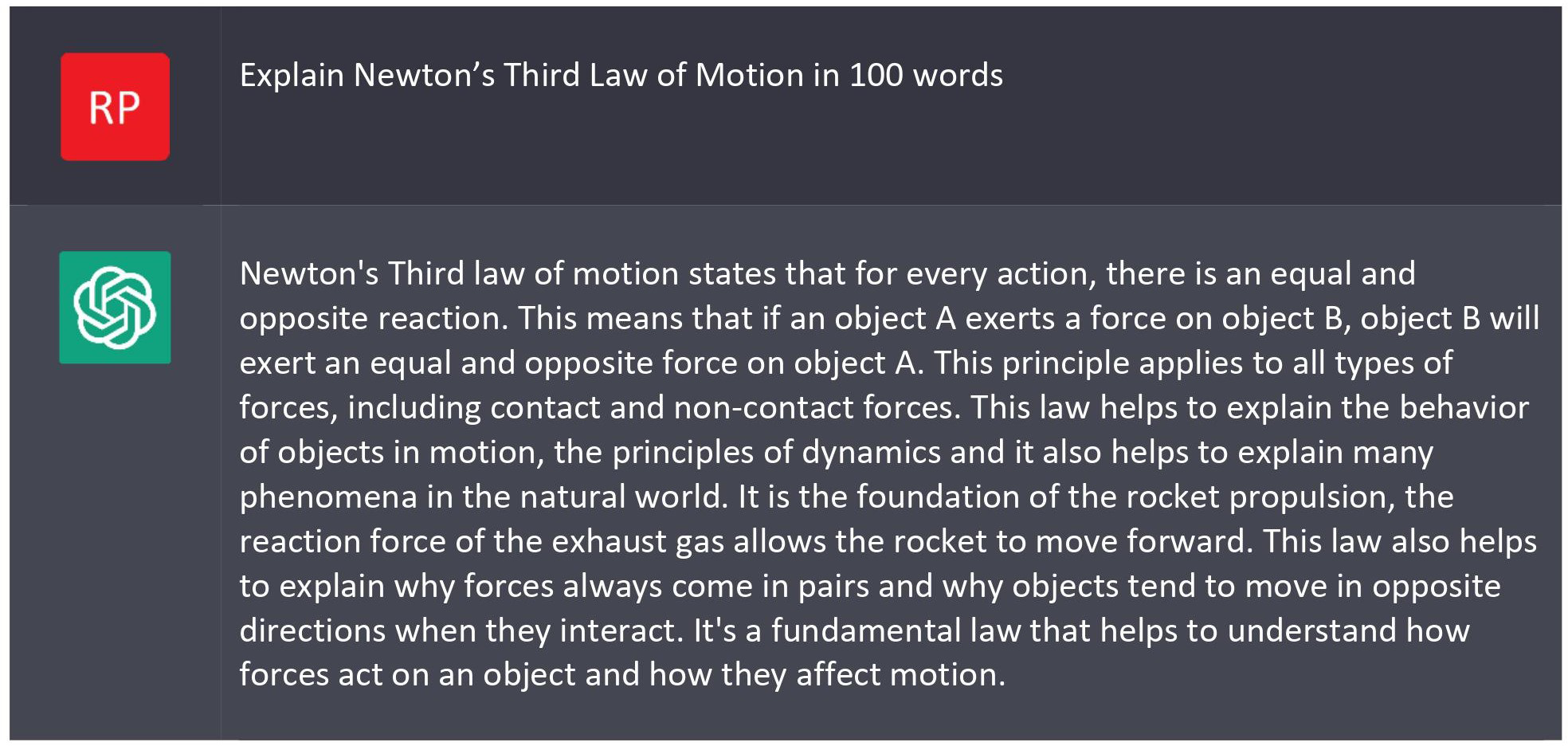

Short answer questions are common in textbooks, and also on tests. I tested ChatGPT with a simple question about Newton’s laws of motion.

This is a reasonable statement of Newton’s laws, if a bit lacklustre. It’s not really an explanation, but the distinction between “explain” and “state” often confuses our students so I’m not surprised a chatbot makes the same mistake.

Repeated requests bring different, but similar, responses (see

Appendix 1).

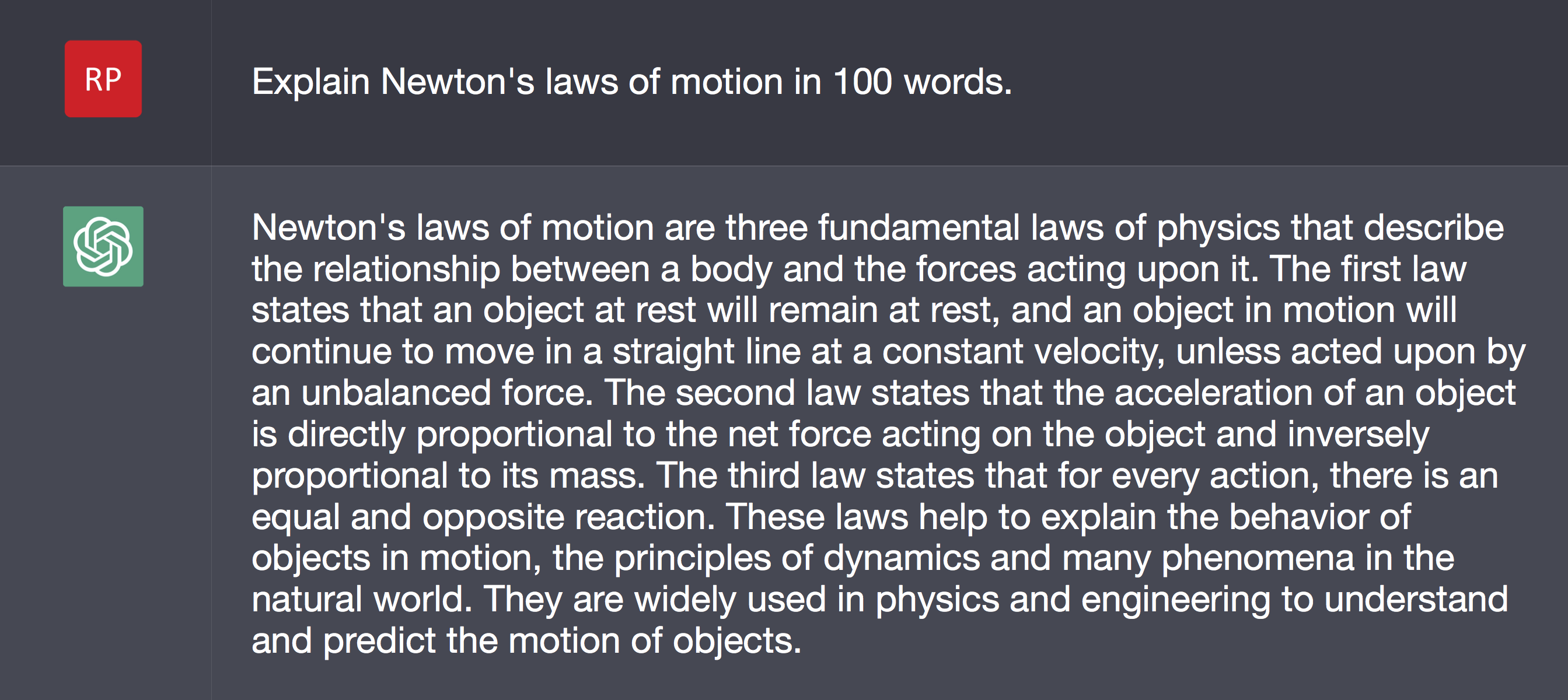

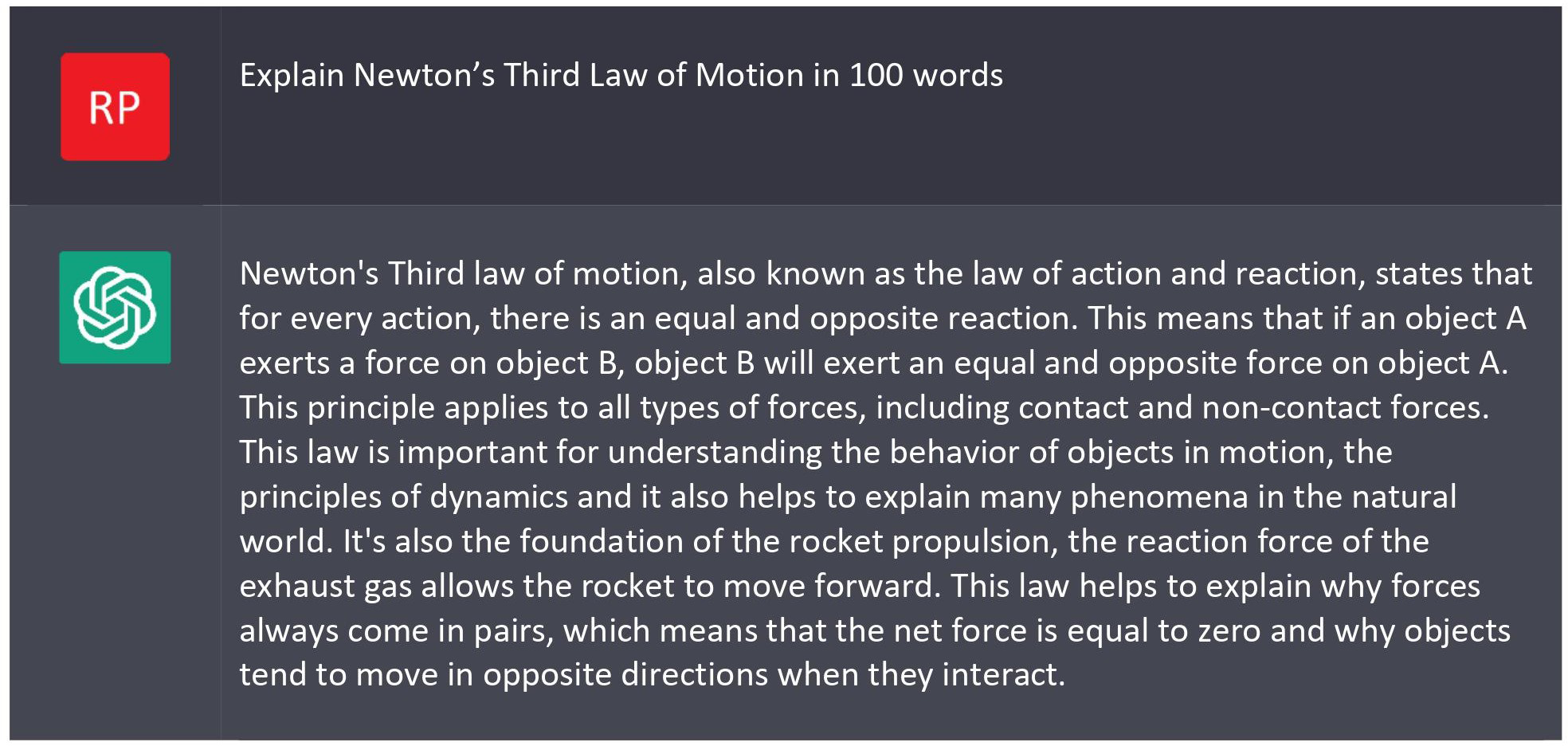

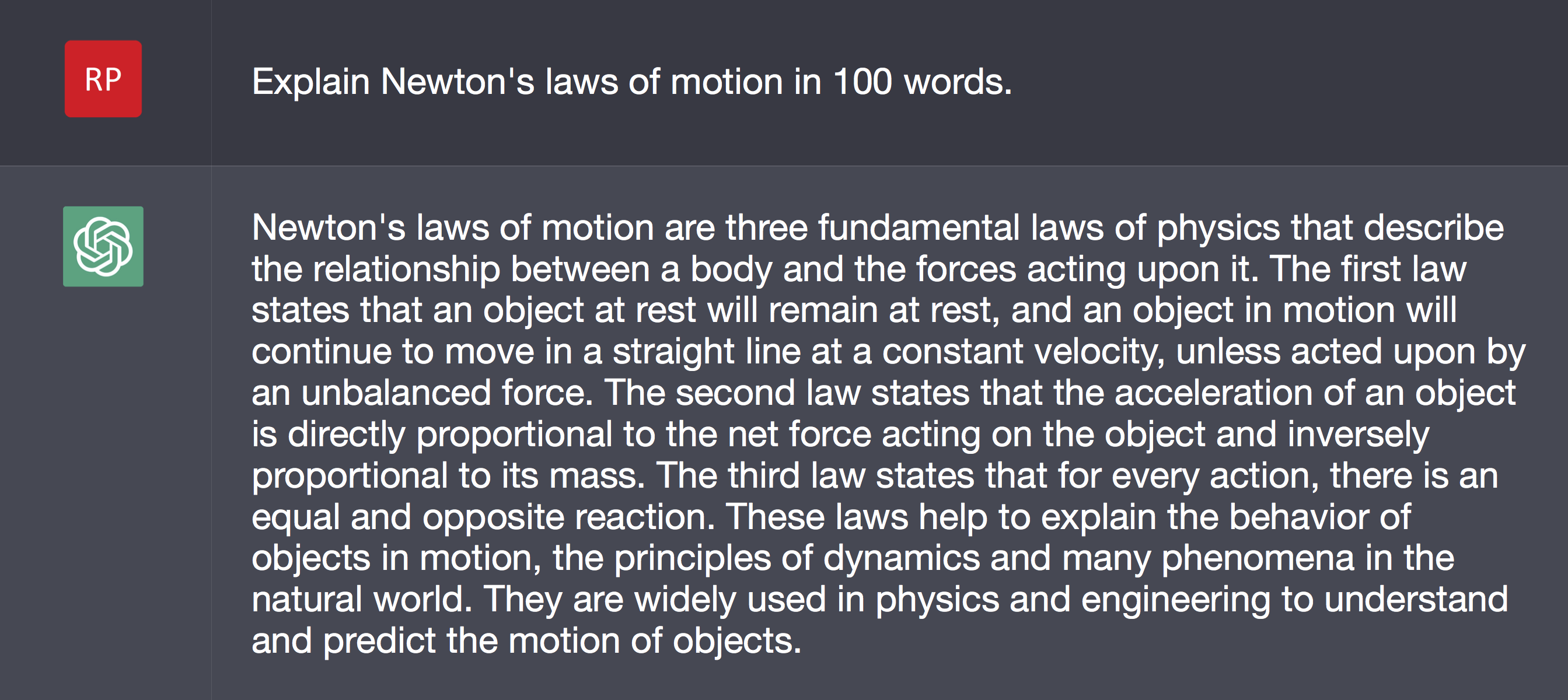

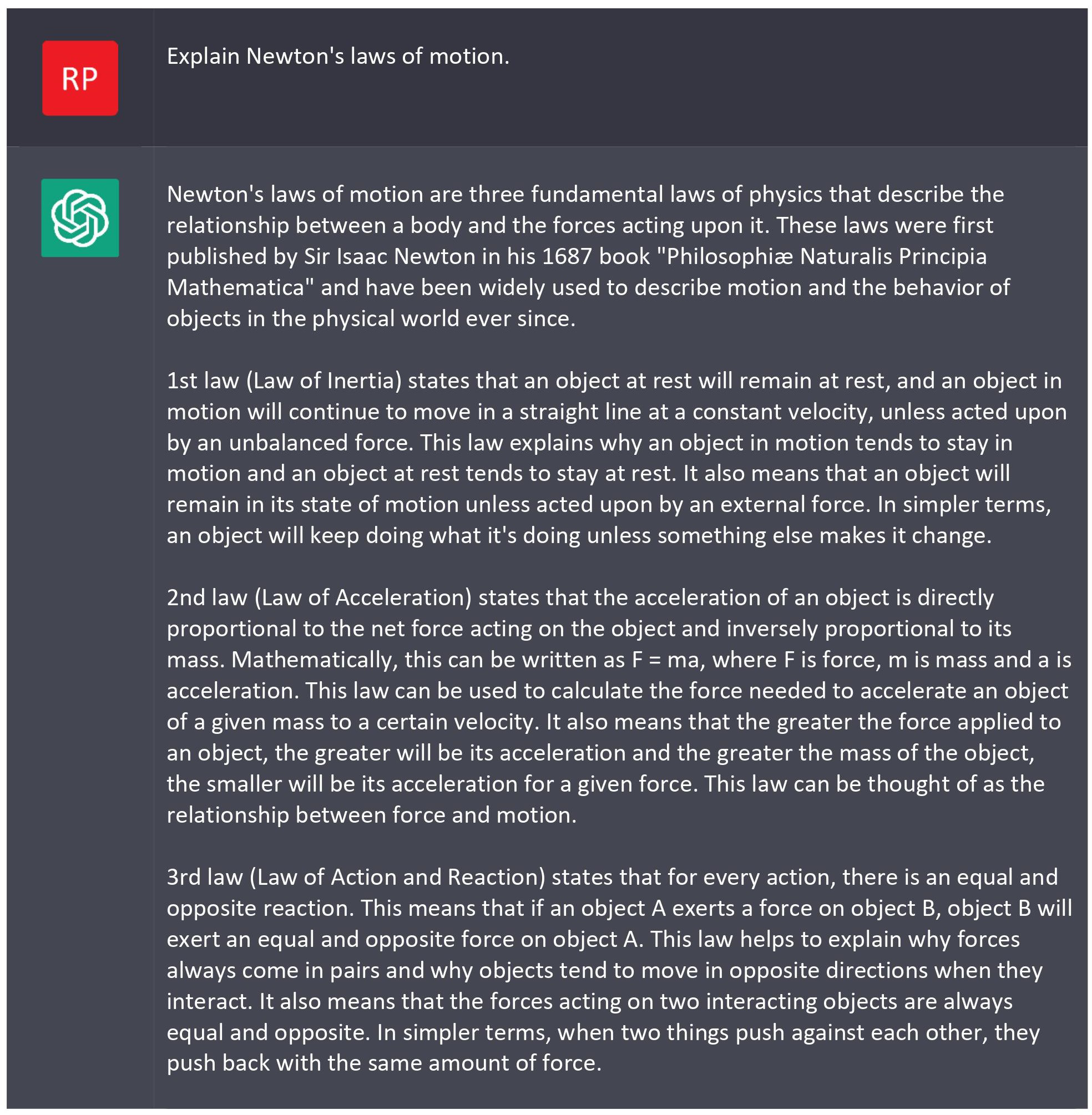

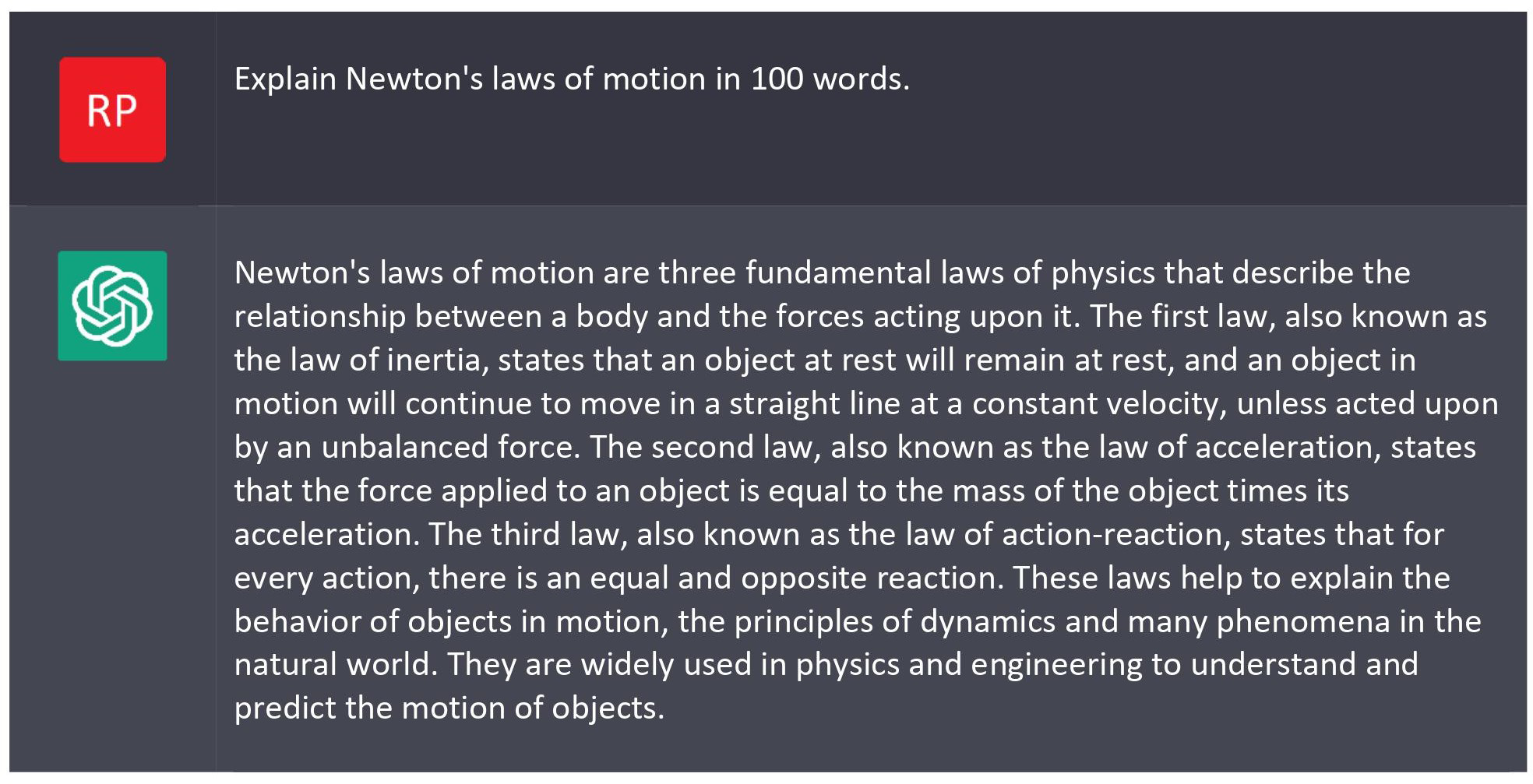

Some of the explanations are pretty long for short answers, so I tried adding a word limit of 100 words.

140 words, not 100. Clearly ChatGPT isn’t good with word count limits, although it does trend shorter than the requests without a limit. Repeated requests bring different, but similar, responses (see

Appendix 1).

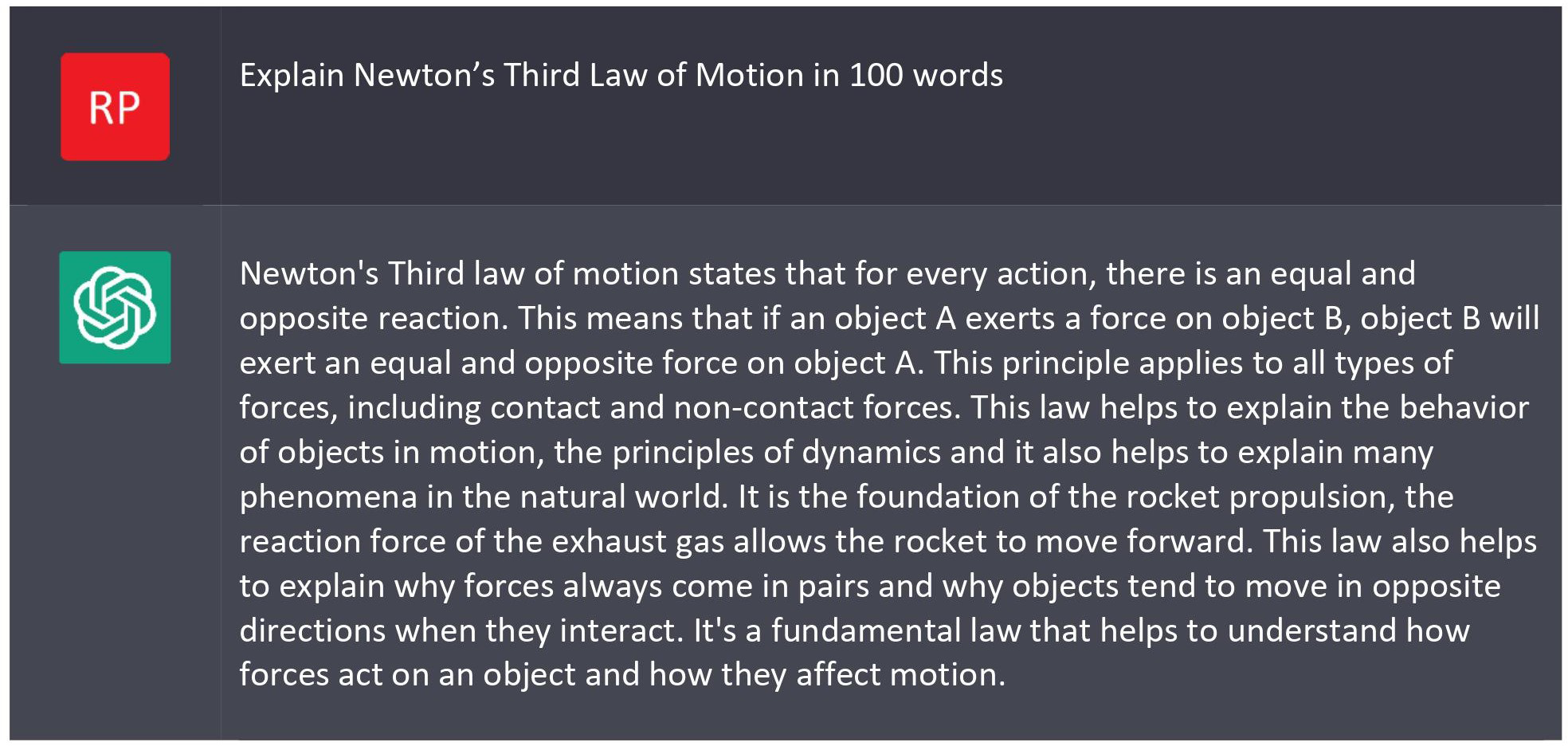

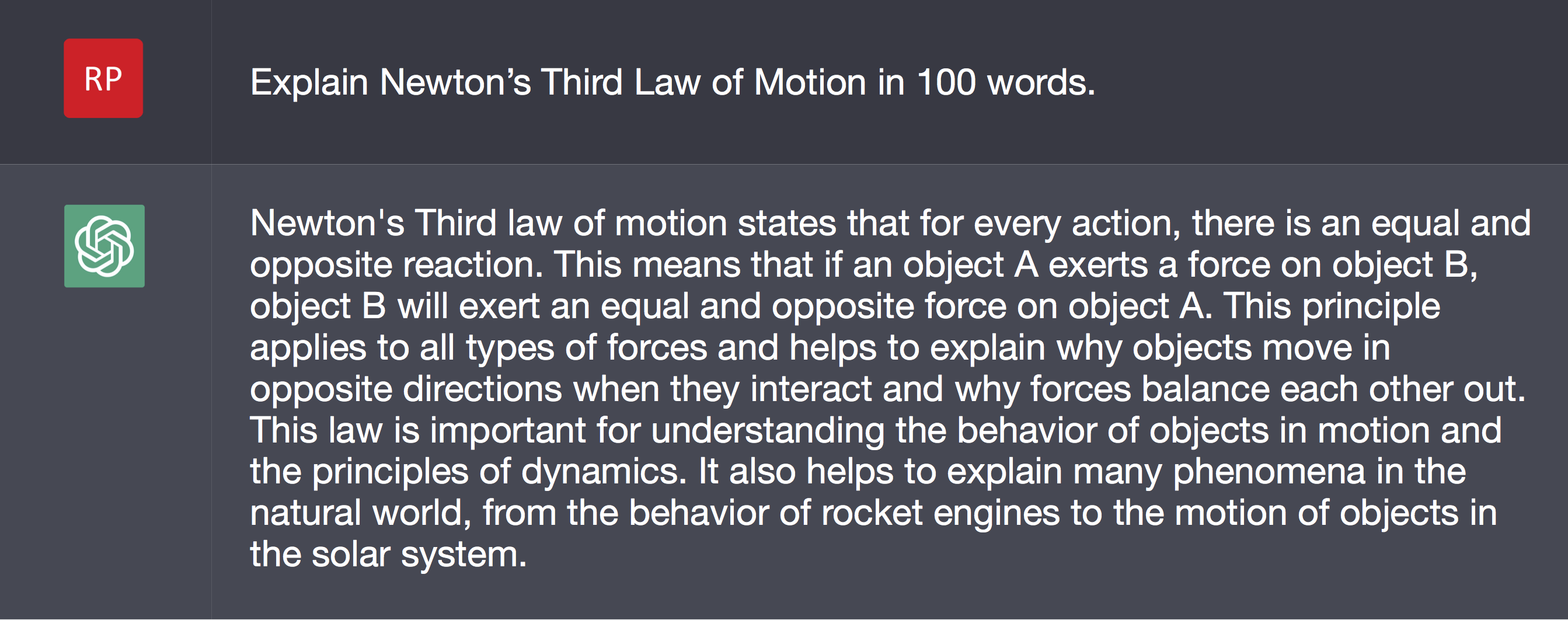

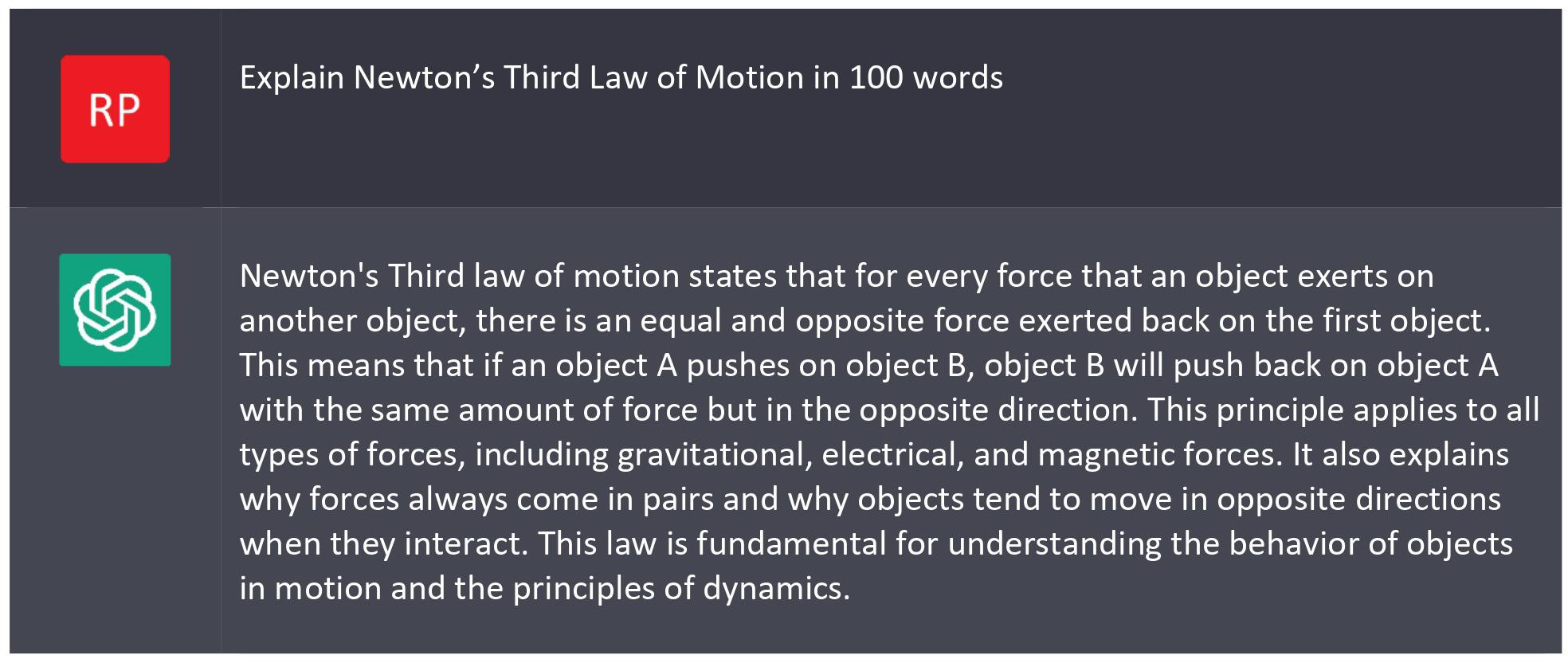

On a test we often ask students to explain one specific law or concept, so I tried being more specific.

Repeated requests bring a different, but similar, responses (see

Appendix 1).

As you can see, ChatGPT does a reasonable job of answering short answer questions as well as a typical student. It struggles a bit with keeping its responses within constraints.

How well does ChatGPT write essays?

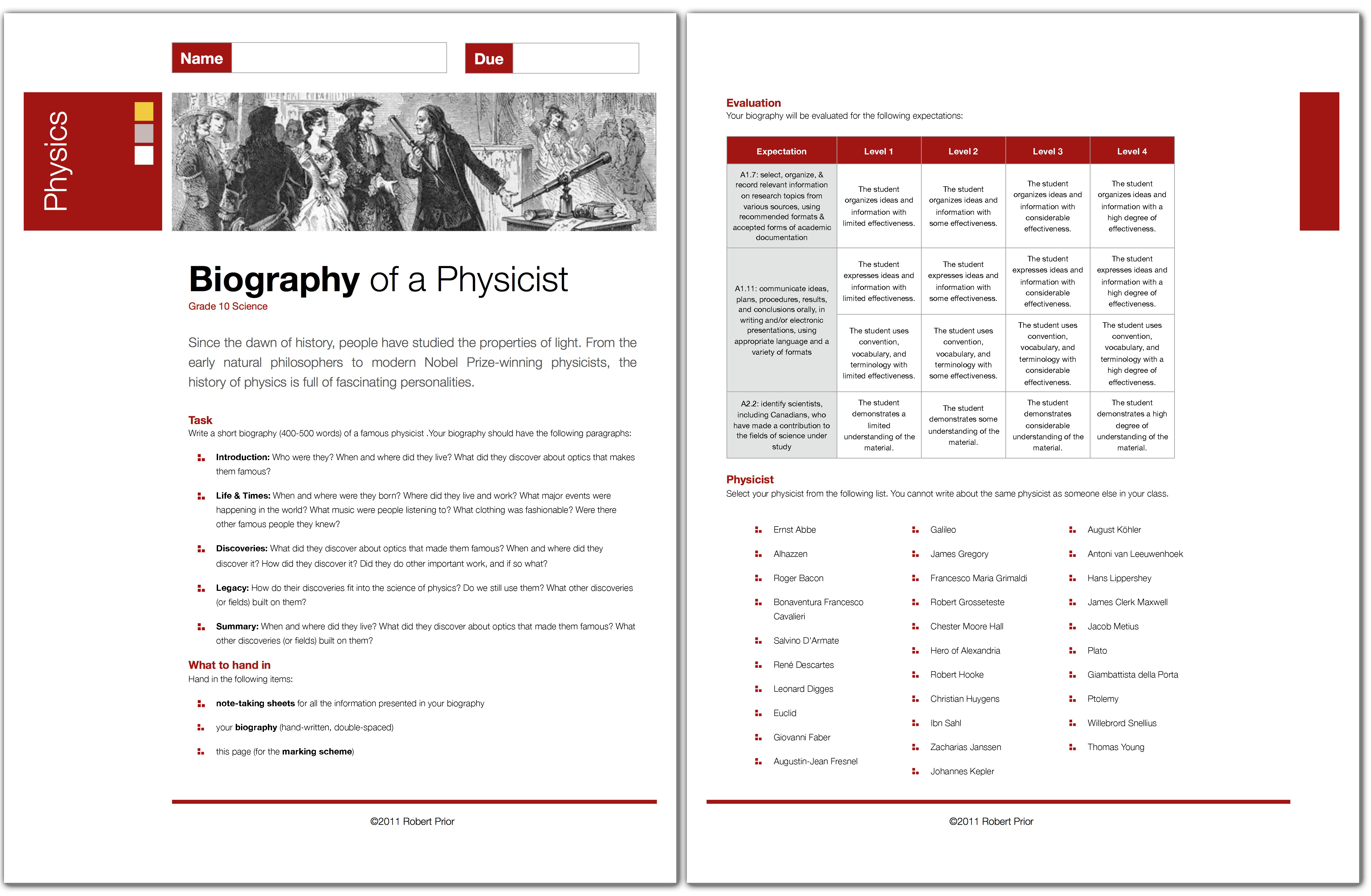

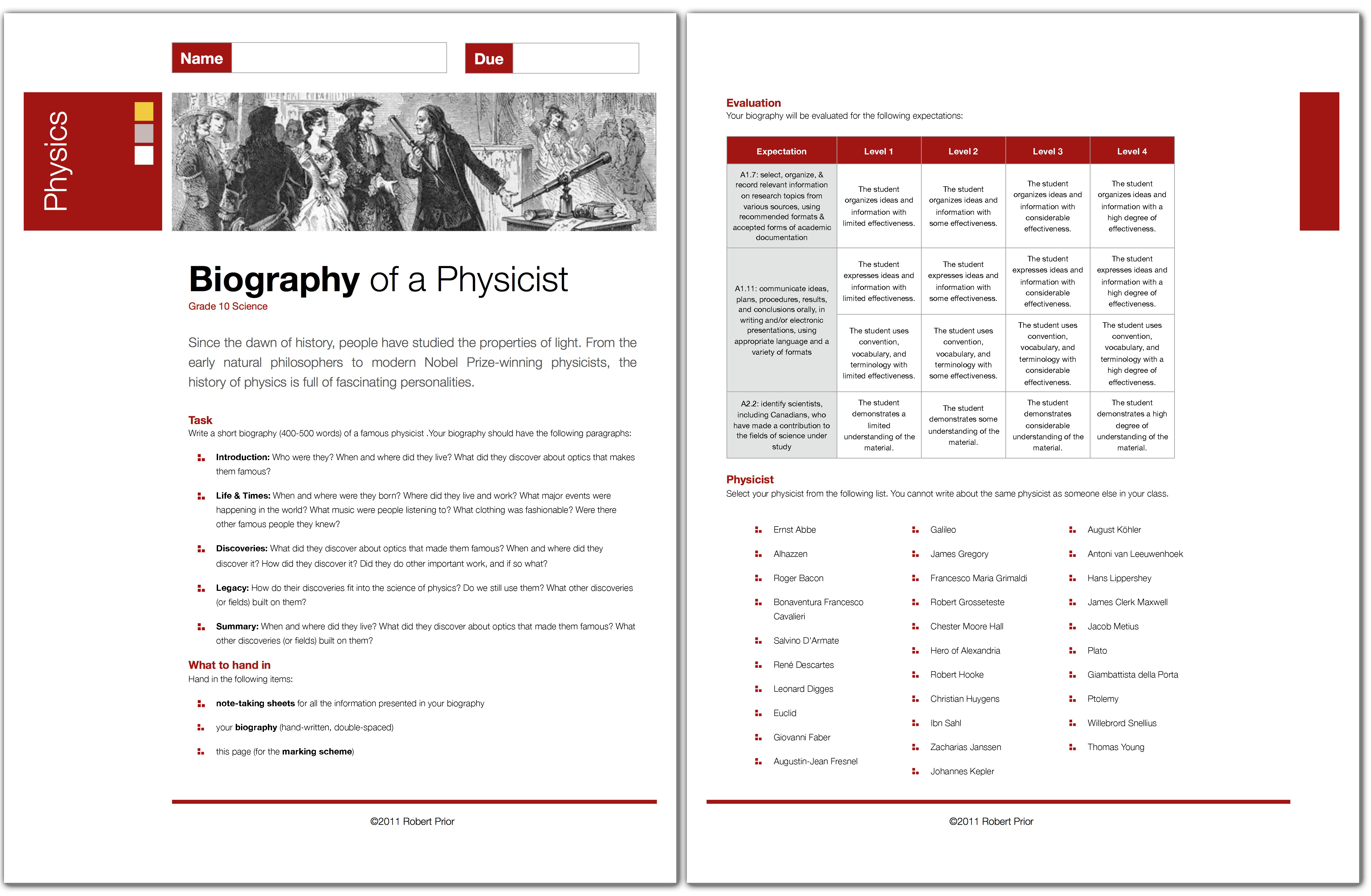

I assign short essays to my grade ten students, partly as practice for the OSSLT and partly because they don’t get much practice writing factual essays (as opposed to opinion essays) in their English classes and I think it’s a valuable skill. I use the five-paragraph format that they were taught in English.

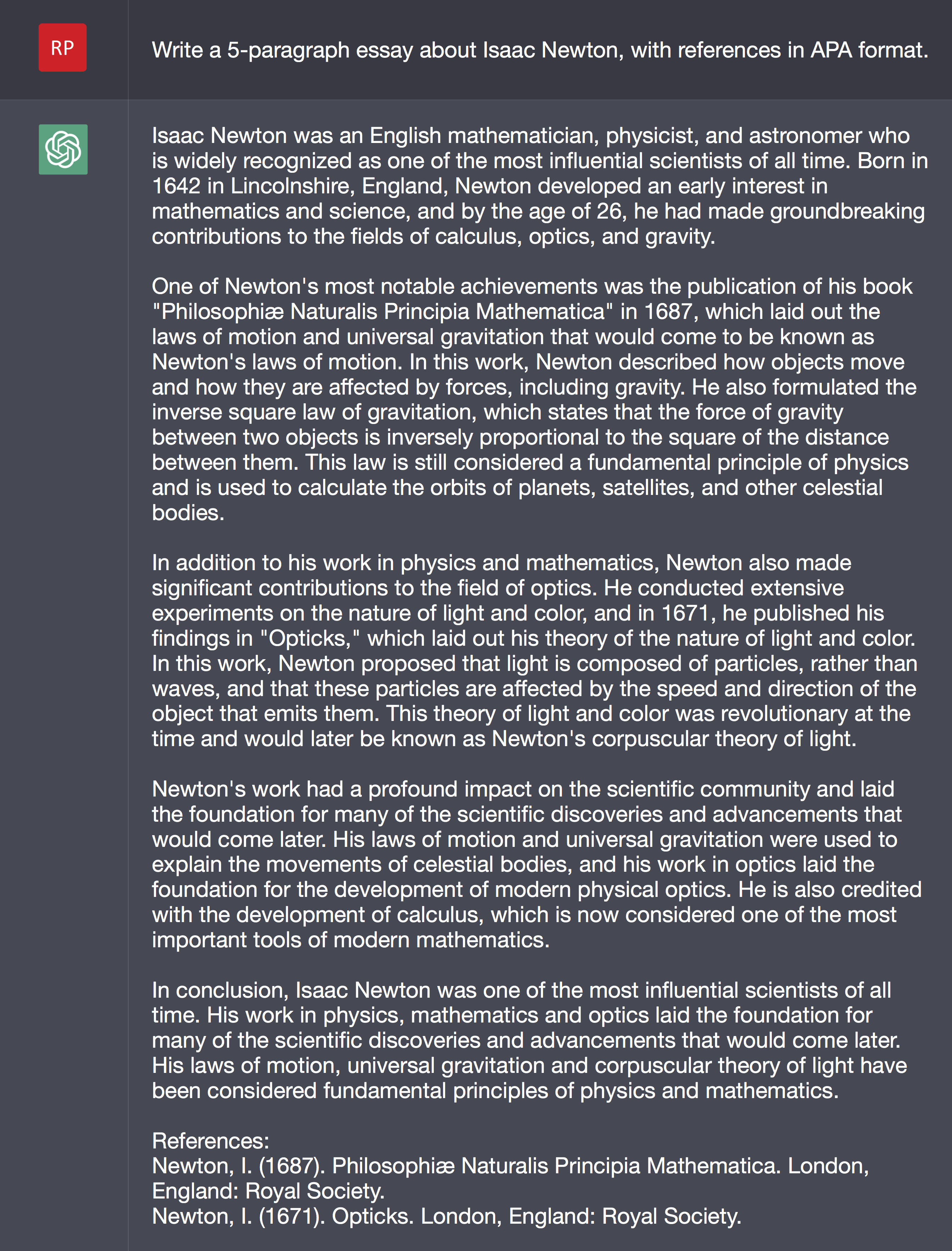

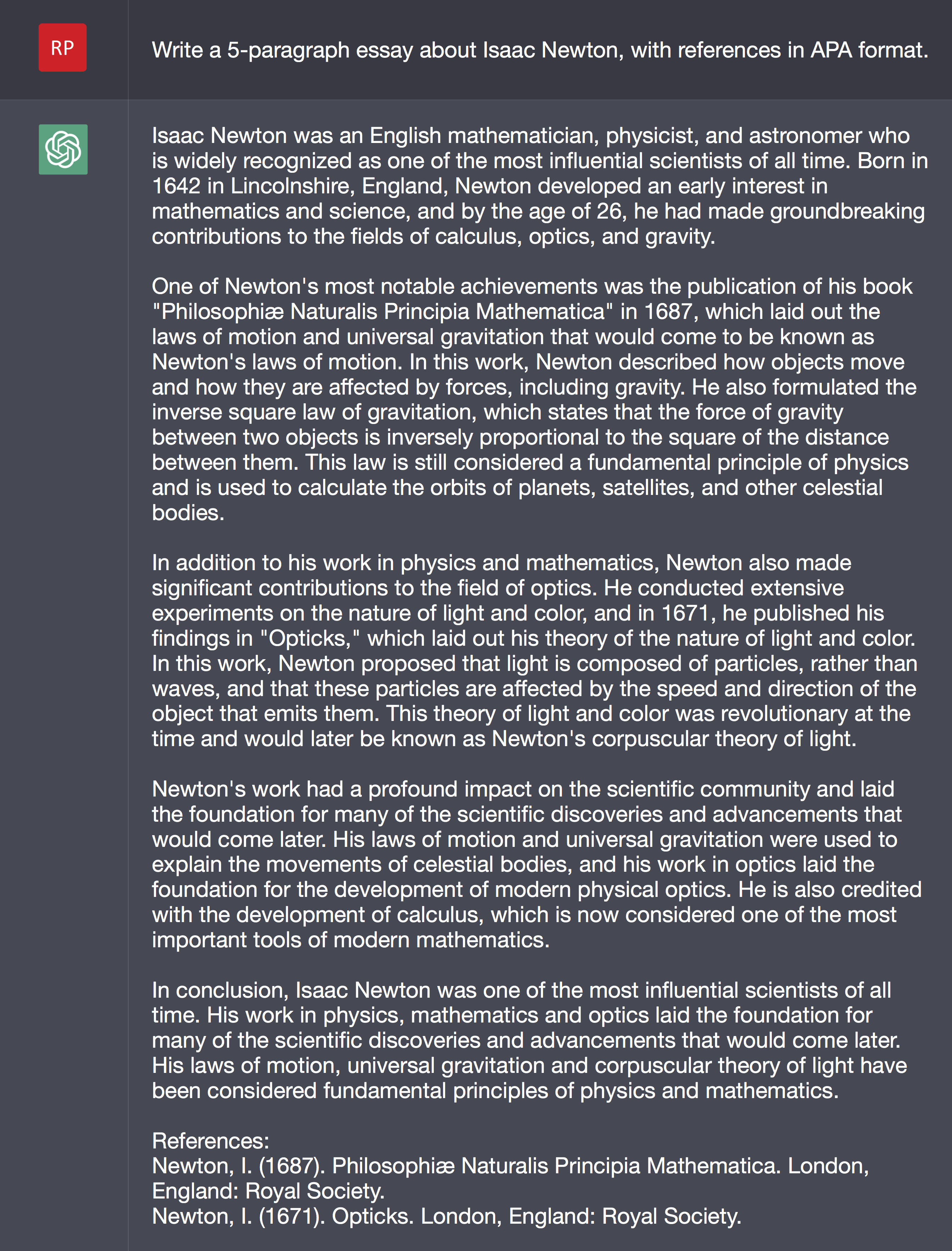

For my first attempt I just asked for a 5-paragraph essay.

I regenerated the response to see how unique it was, and got this:

As you can see, while they are similar the responses are different, although they have common phrases that could appear plagiarized if turned in at the same time. They have a similar structure, but so do most student essays.

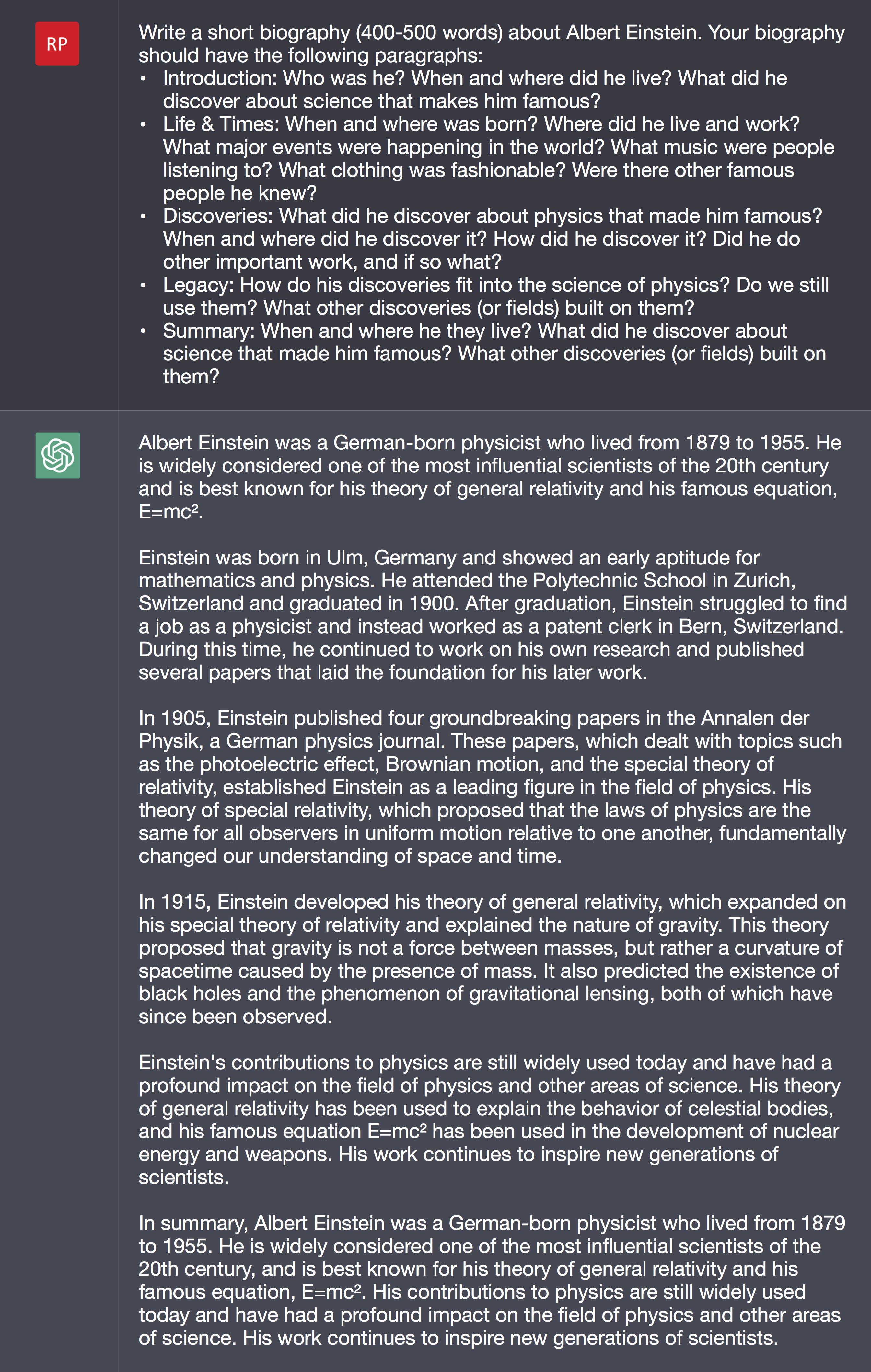

I then got more specific about the essay structure, as I do for my students.

As you can see, while it is similar to the first responses it manages to follow the requested structure quite closely.

My next test was to be as prescriptive as I am for this assignment (which is practice for the OSSLT, so following instructions is important).

The responses were about what I expected, and very similar to the earlier responses. One notable problem is that ChatGPT wasn’t able to infer the number of paragraphs from a simple listing of what each should contain. (Notice how this essay has six paragraphs!)

In addition to having an extra paragraph, this essay has all the flaws of the earlier ones. In particular, the second paragraph doesn’t place Einstein in his historical context. Despite these flaws, I have to admit that I would have given any of these essays a passing grade and wouldn’t have considered them any more plagiarized than most student essays (which often simply paraphrase source material).

Speaking of source materials, can ChatGPT manage to give references?

Well, points for going back to the original source work, but those two sources don’t include many of the biographical details included in the essay. Also, optics is apparently neither physics nor mathematics!

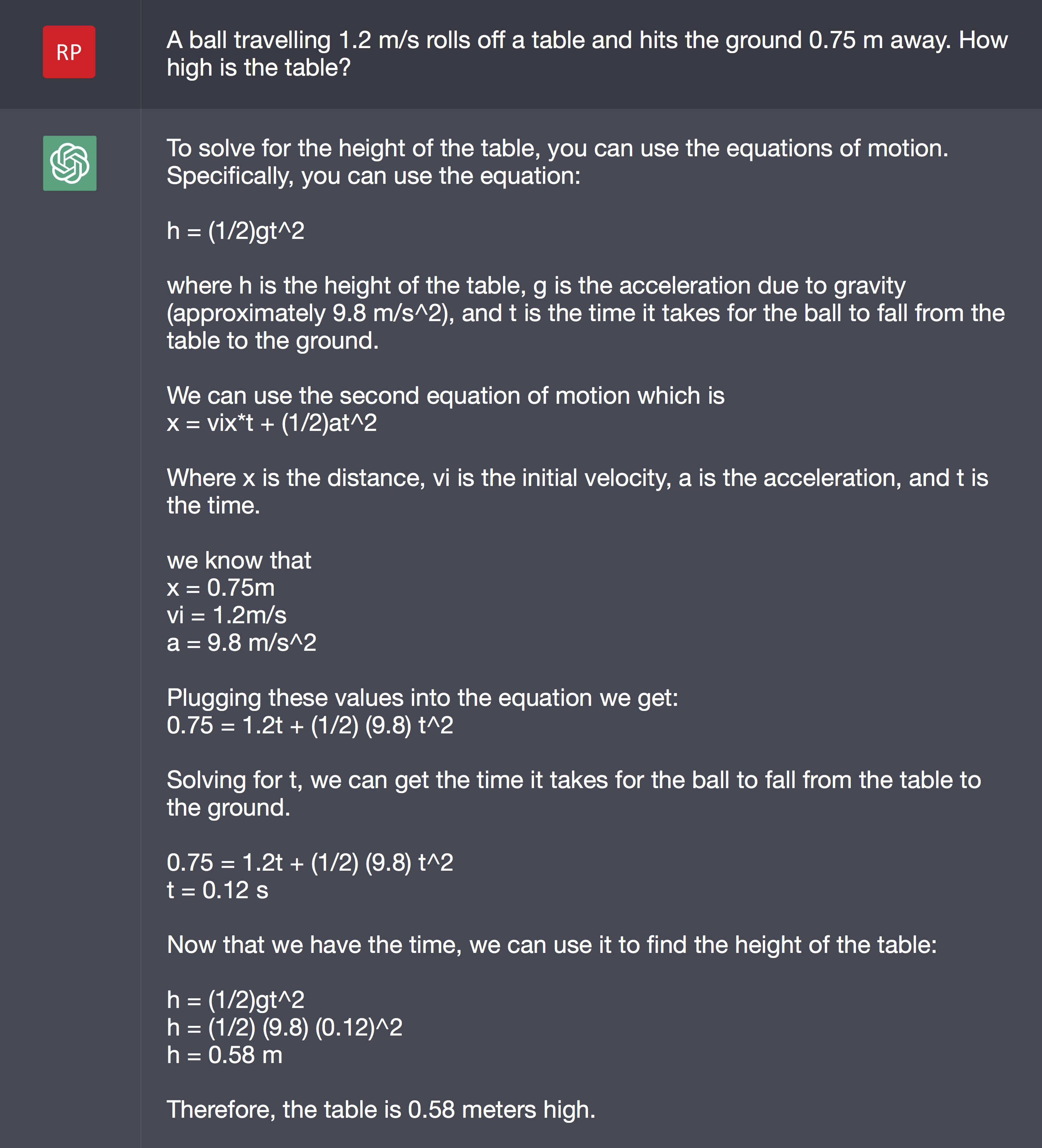

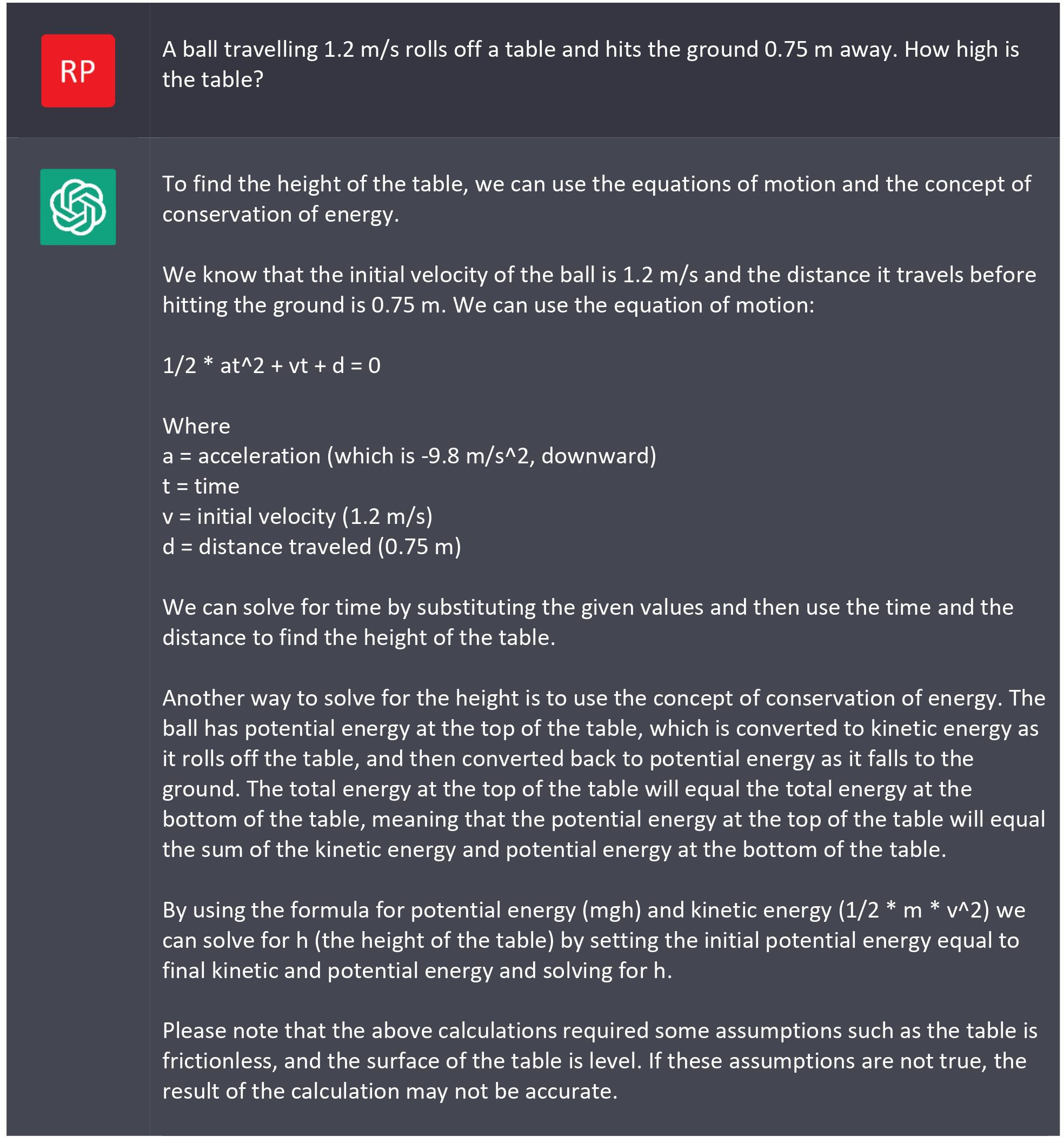

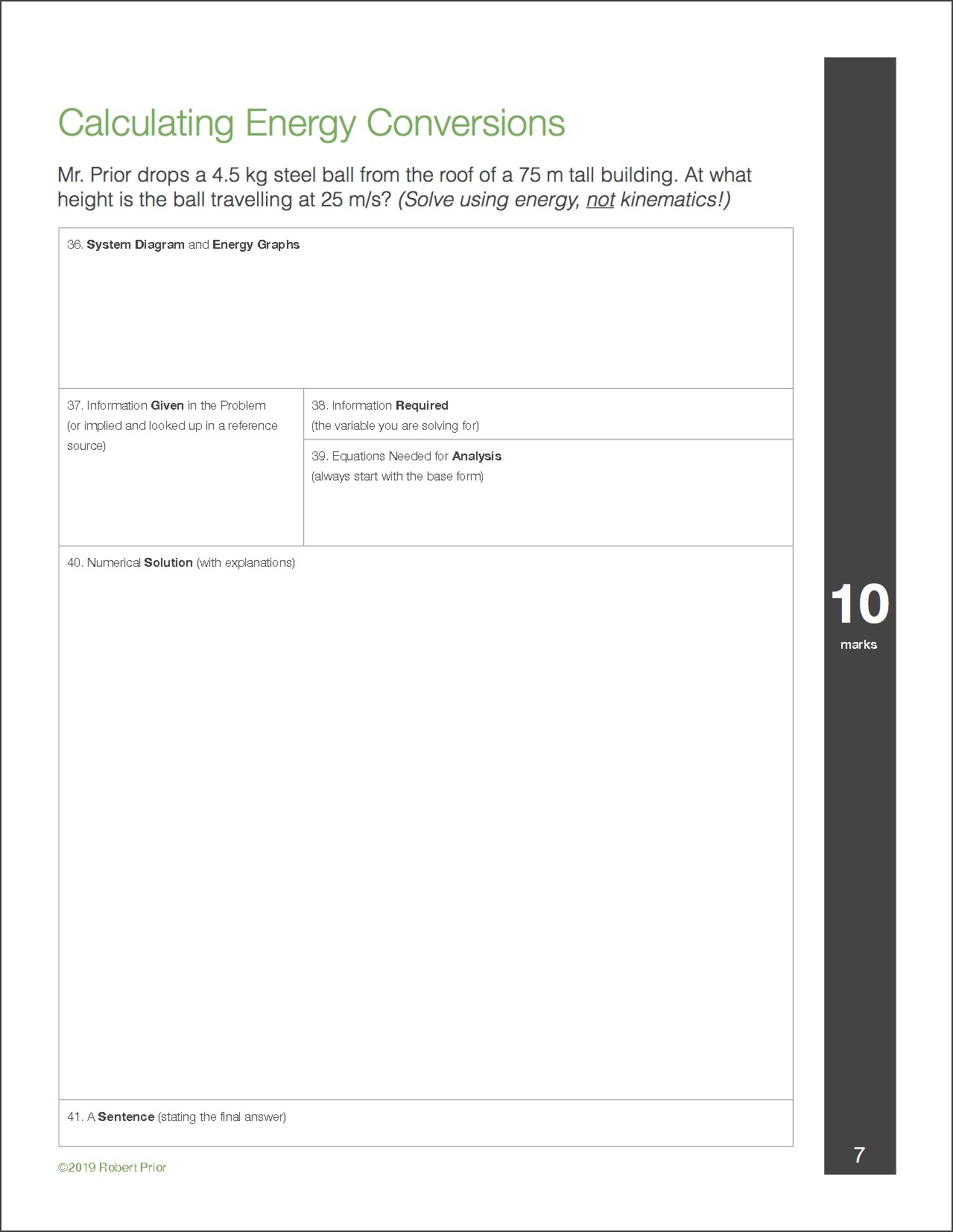

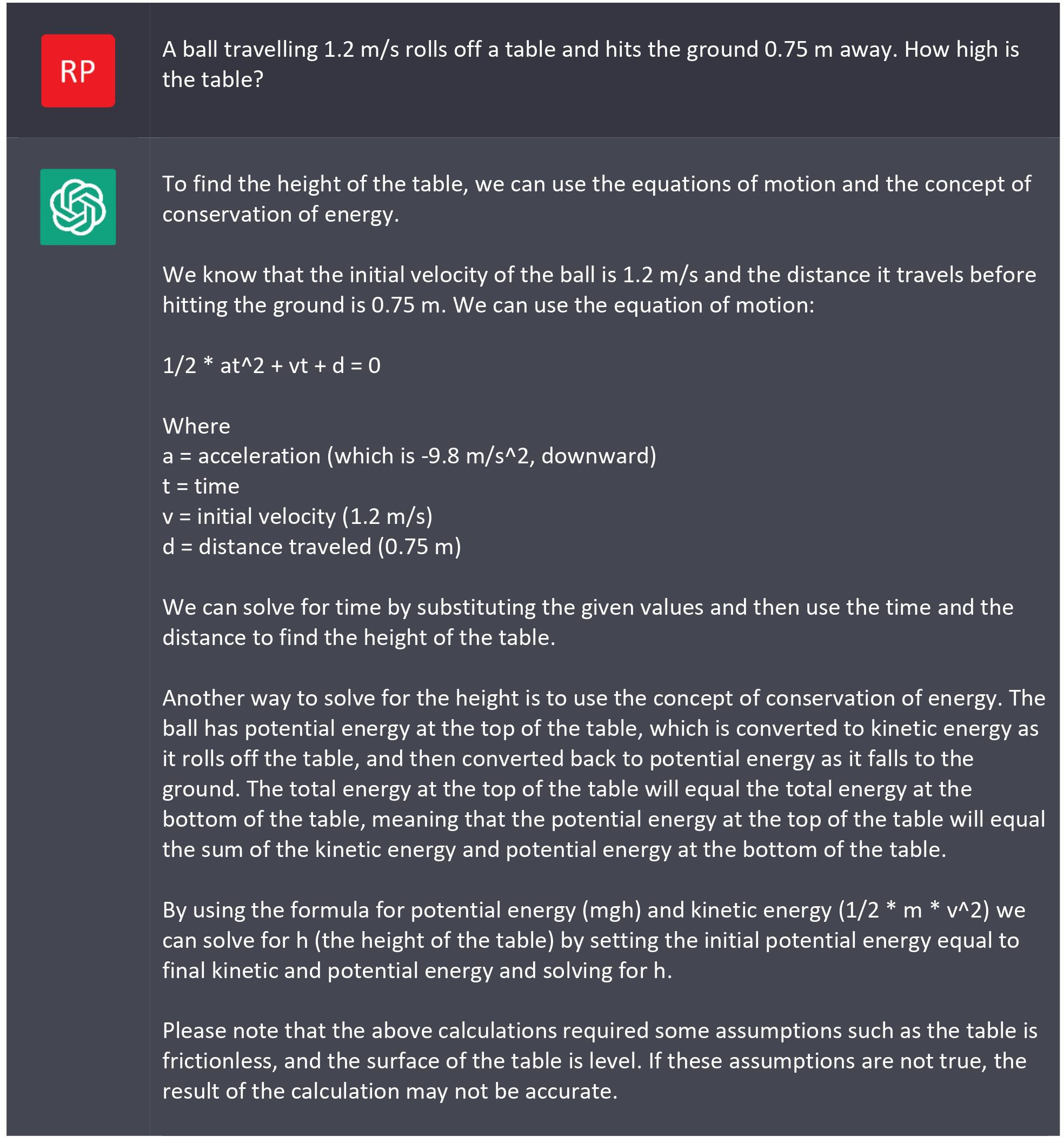

What about physics problems?

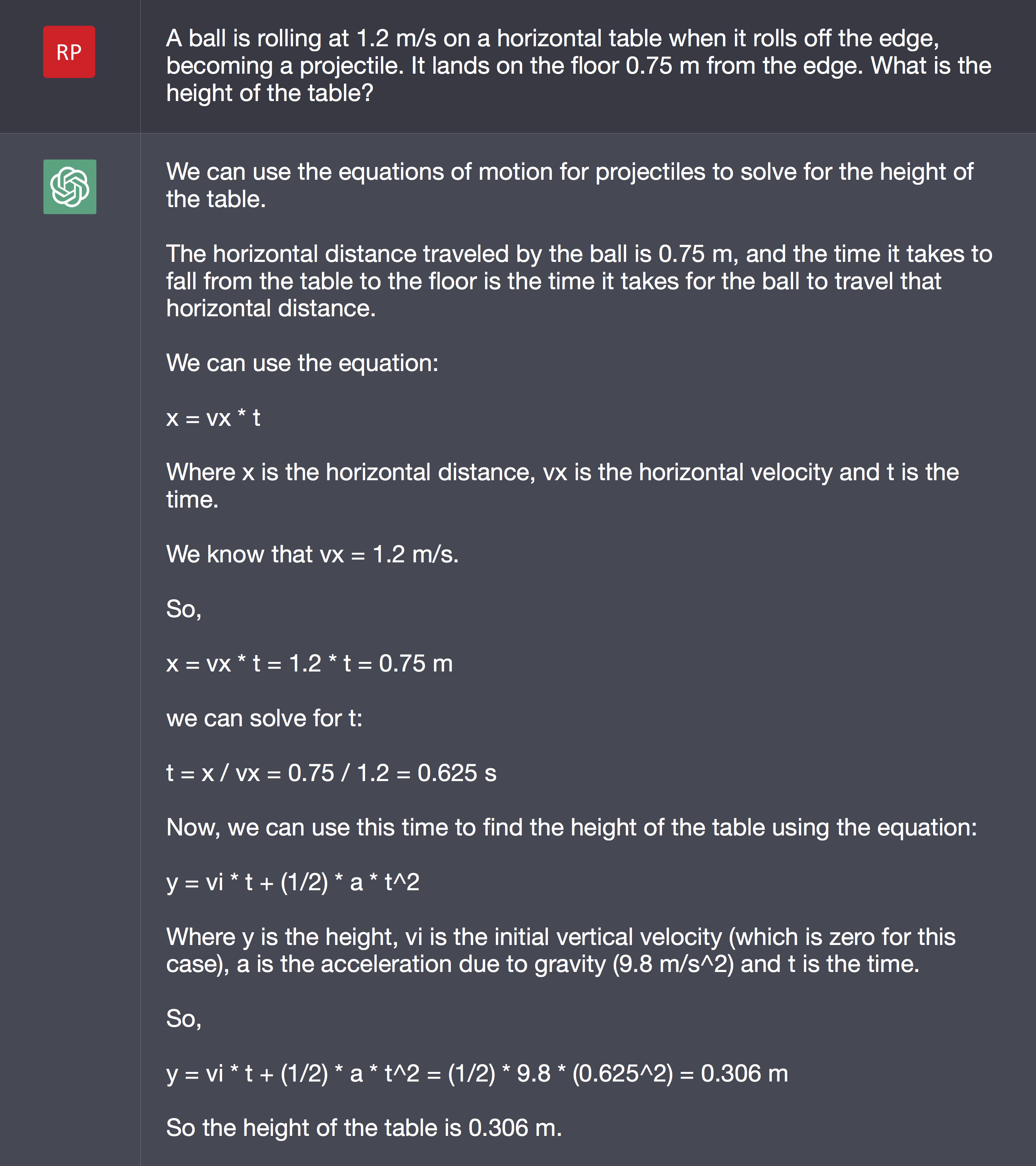

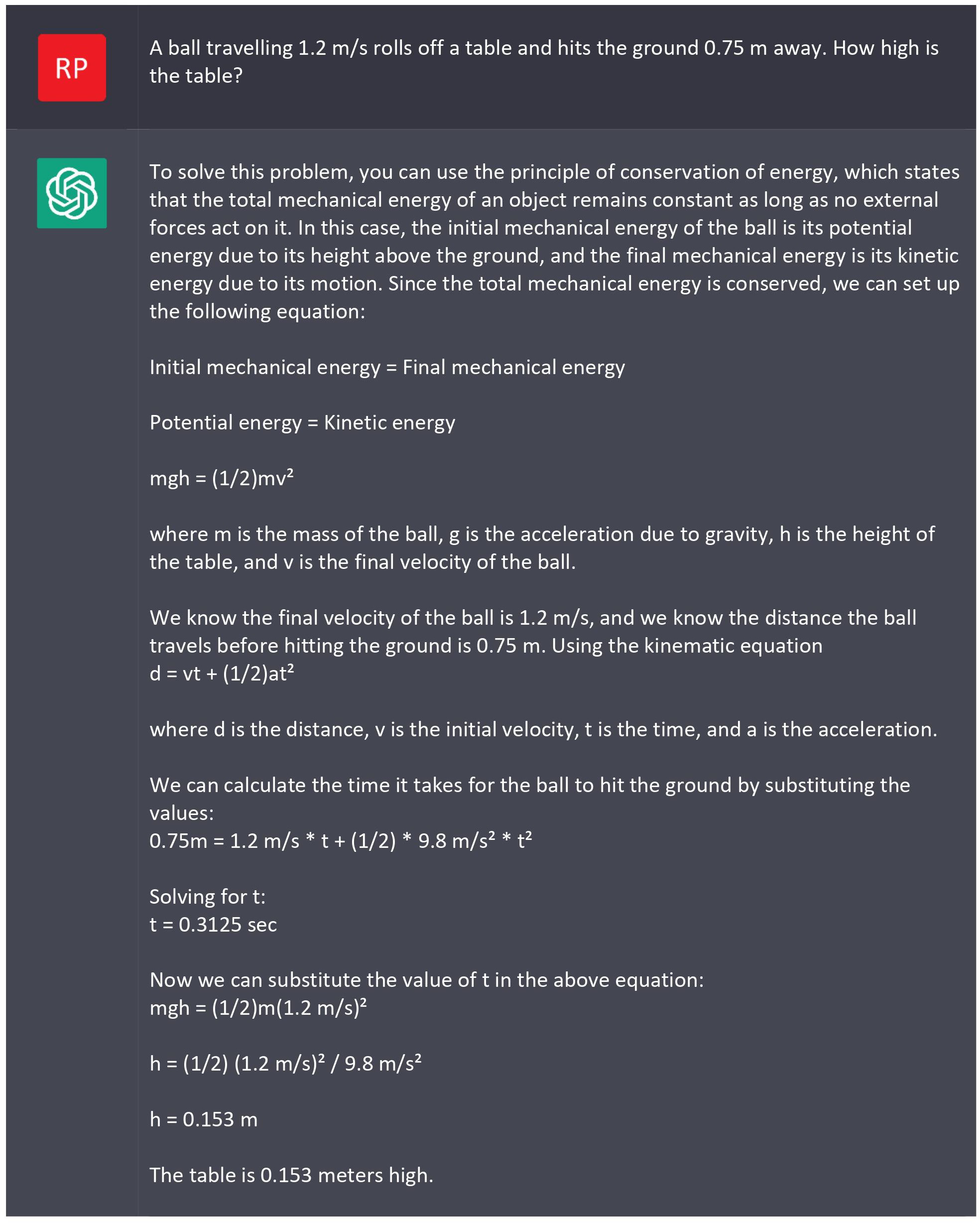

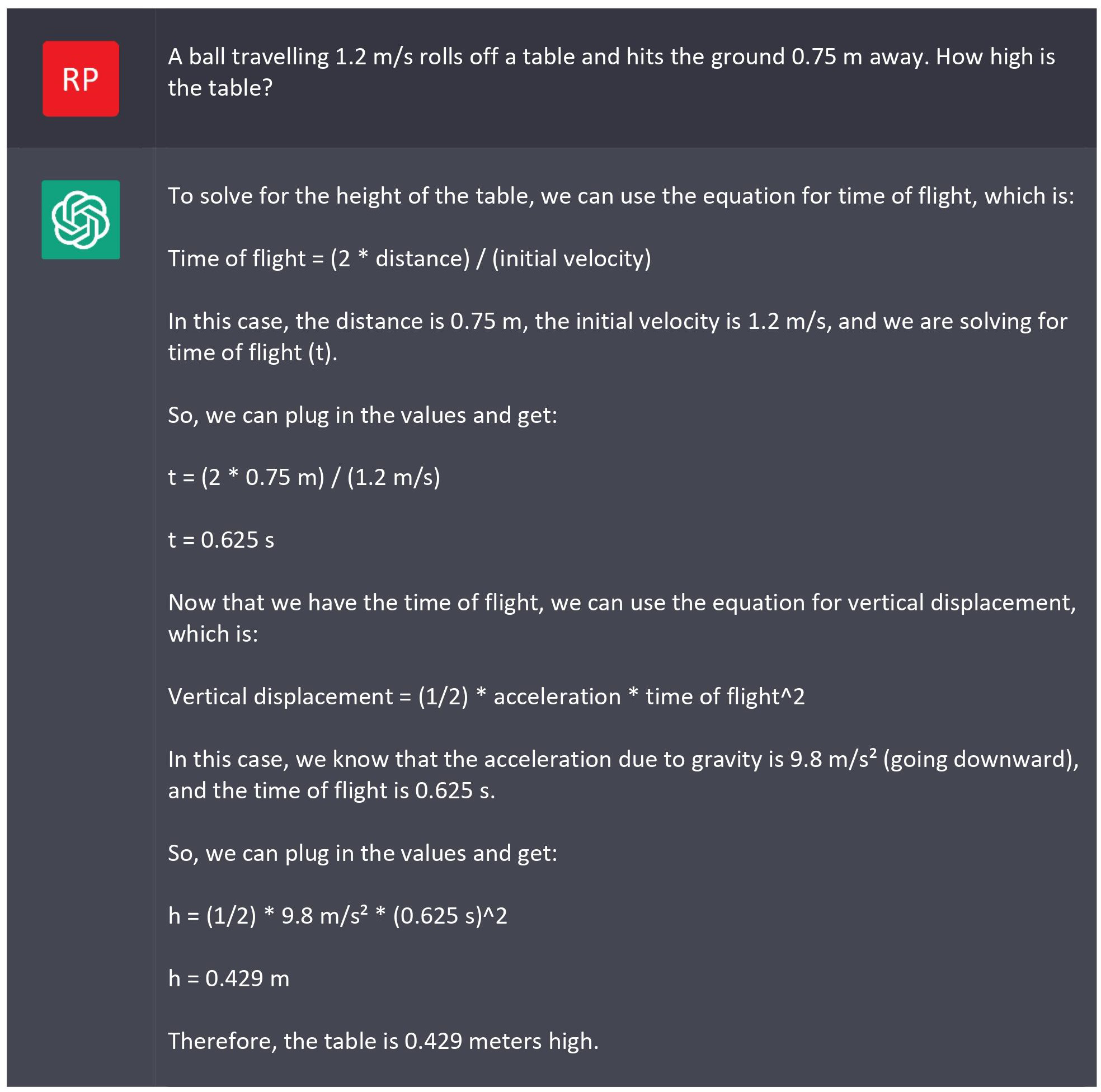

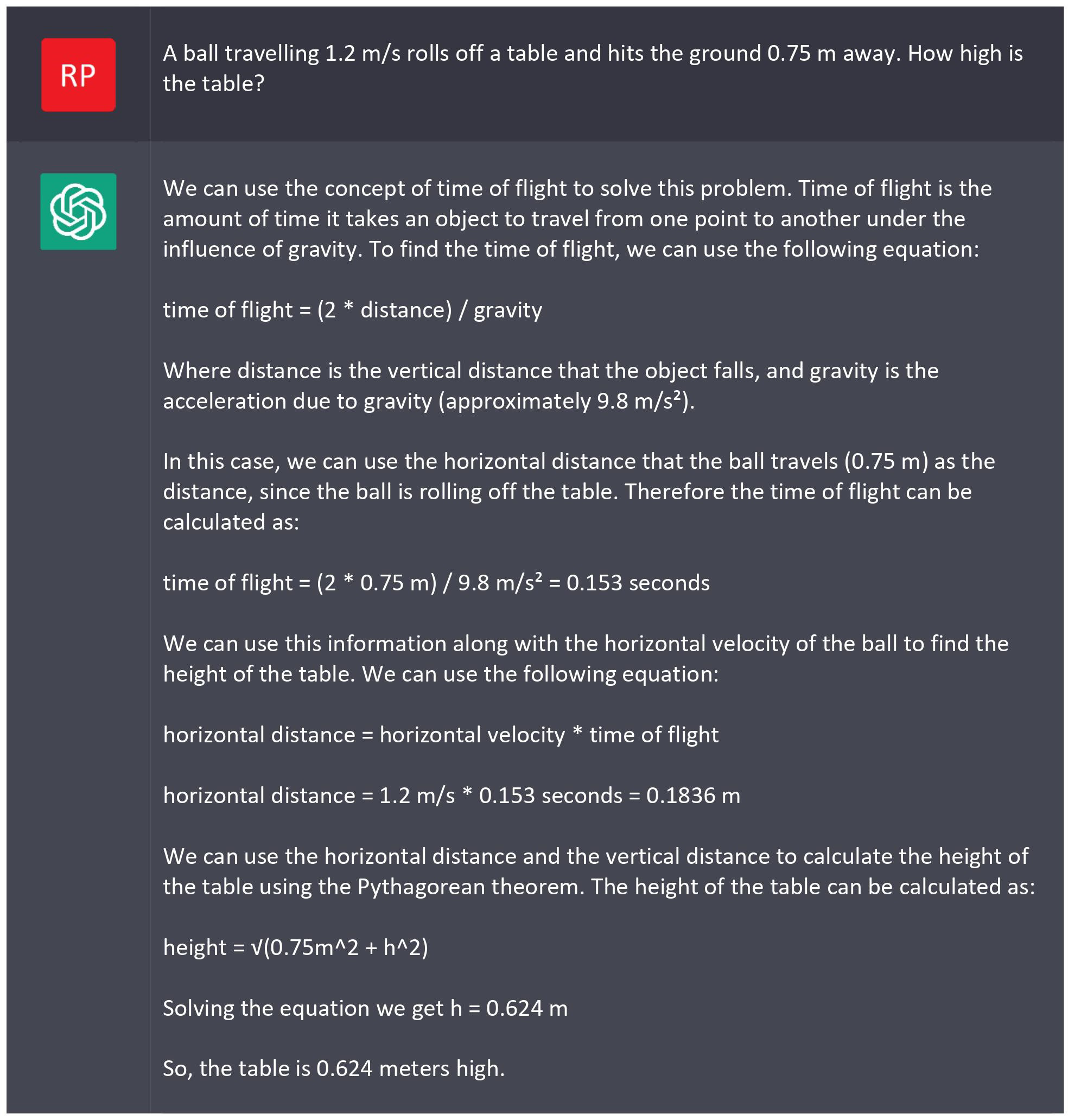

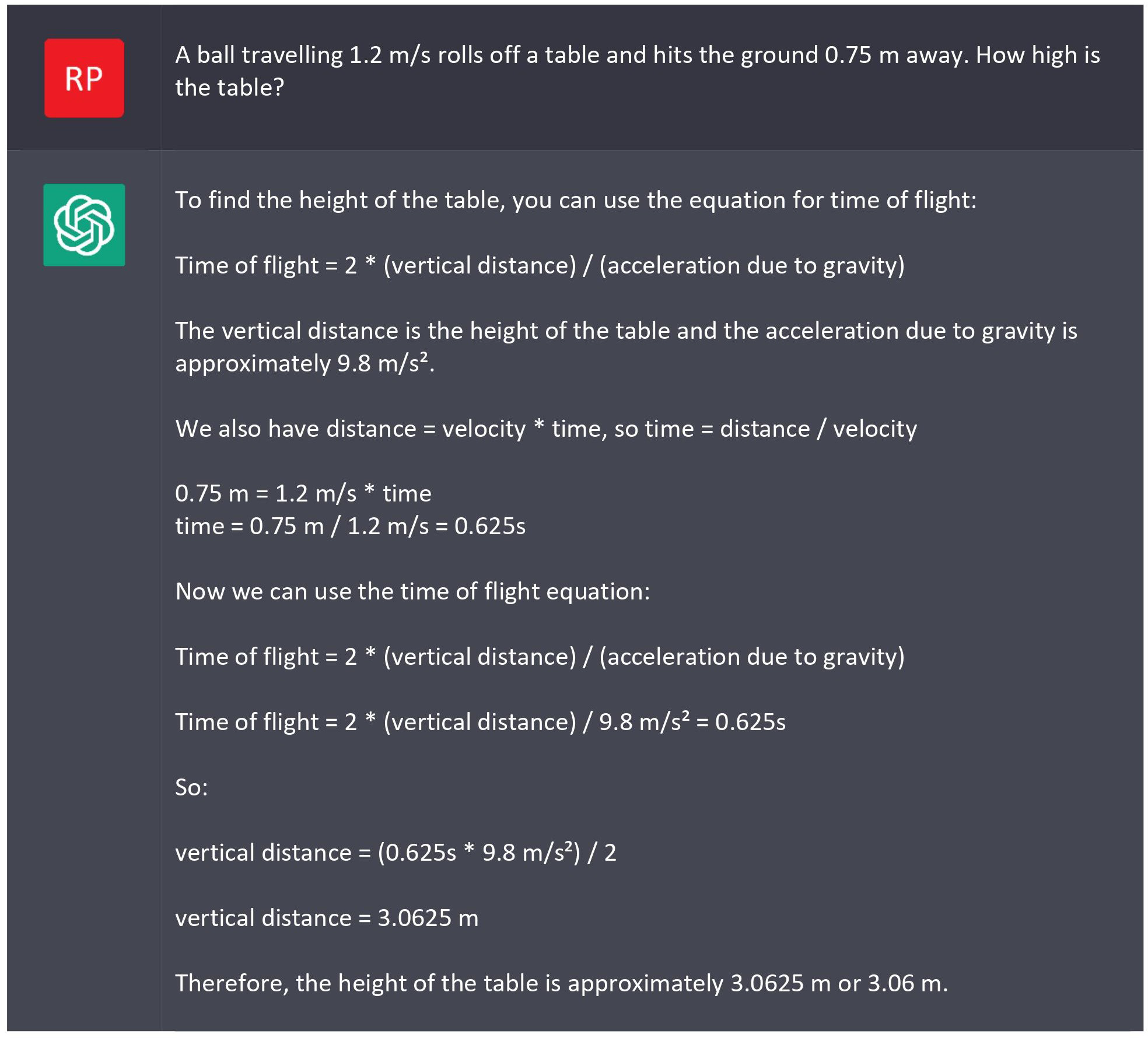

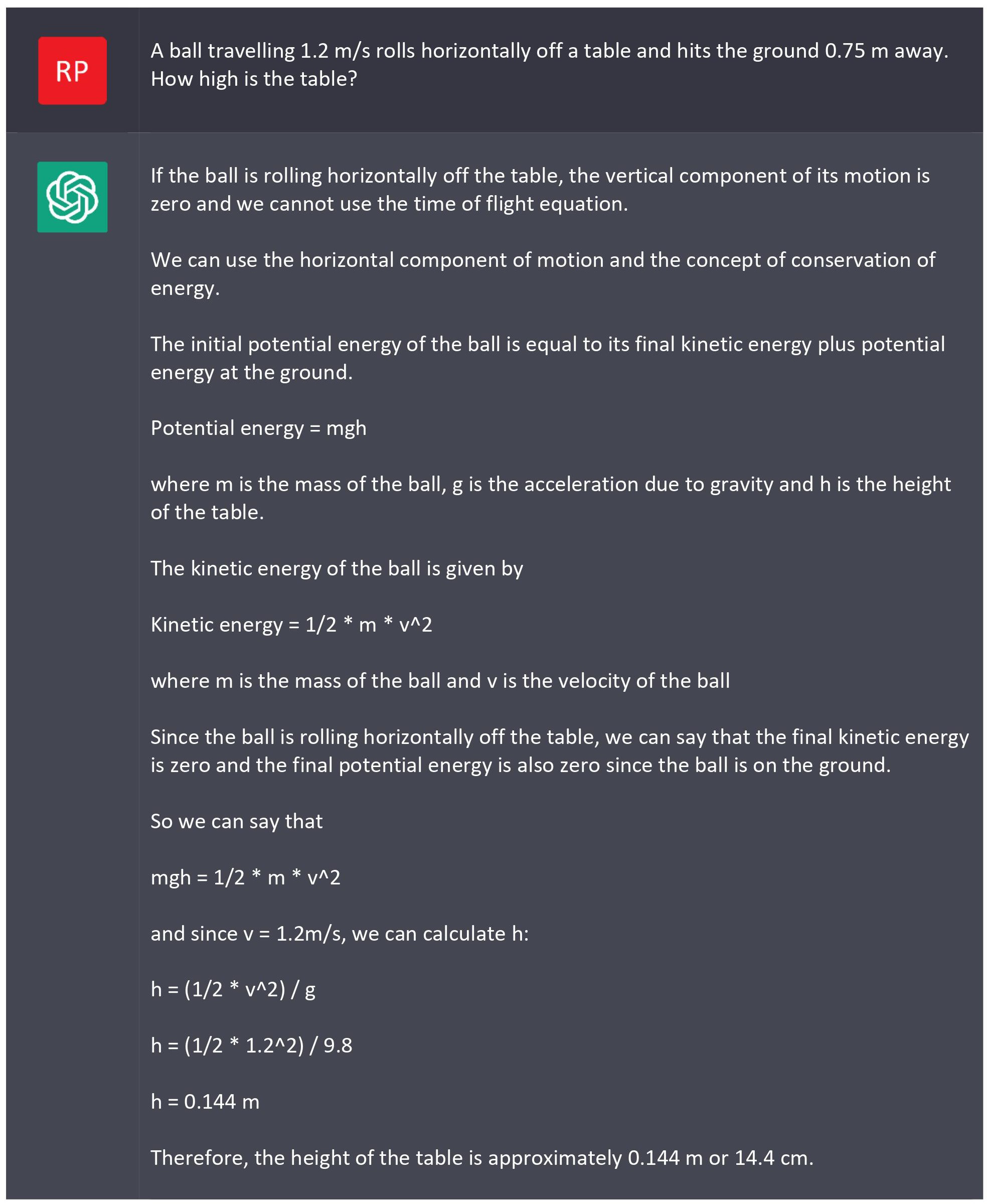

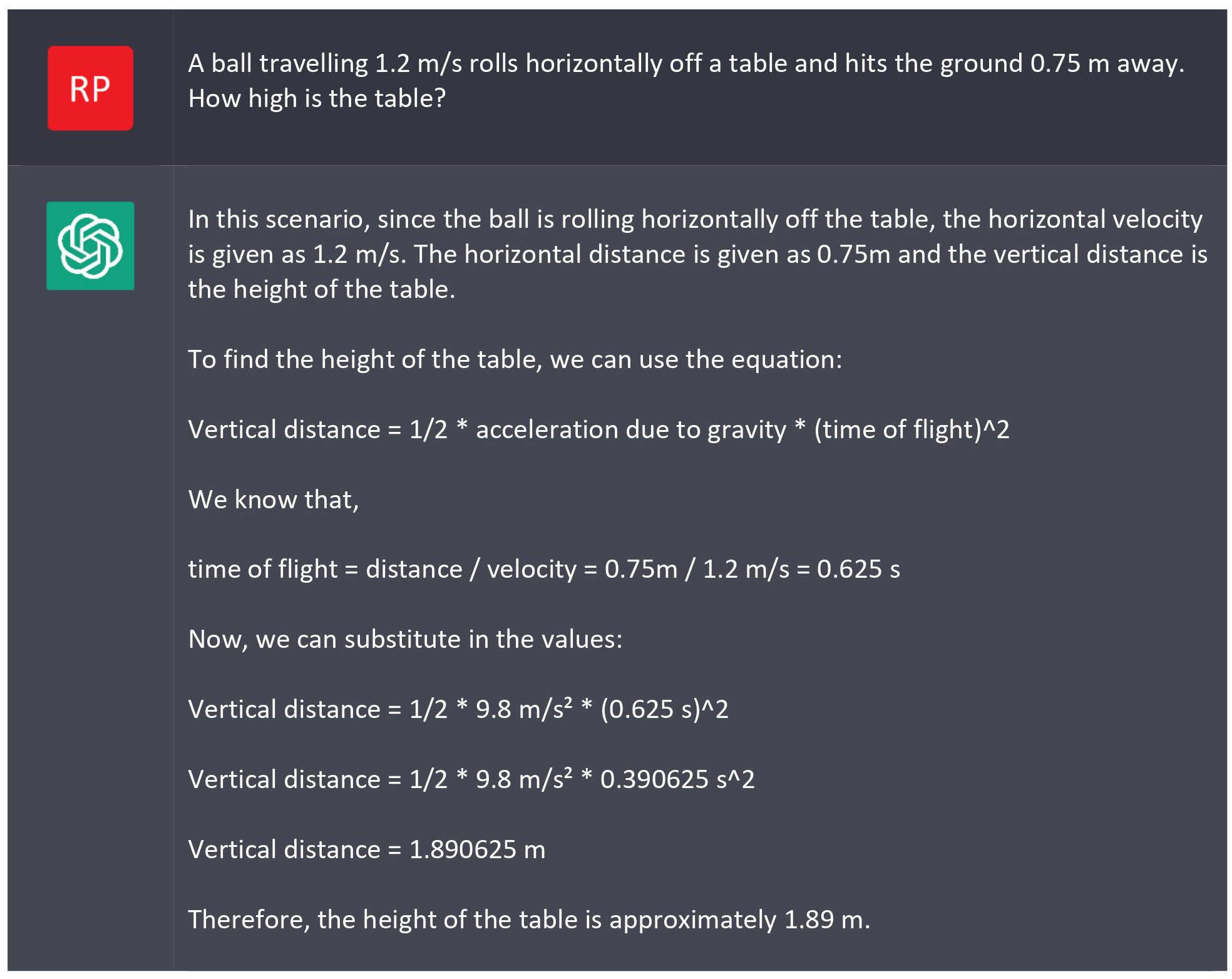

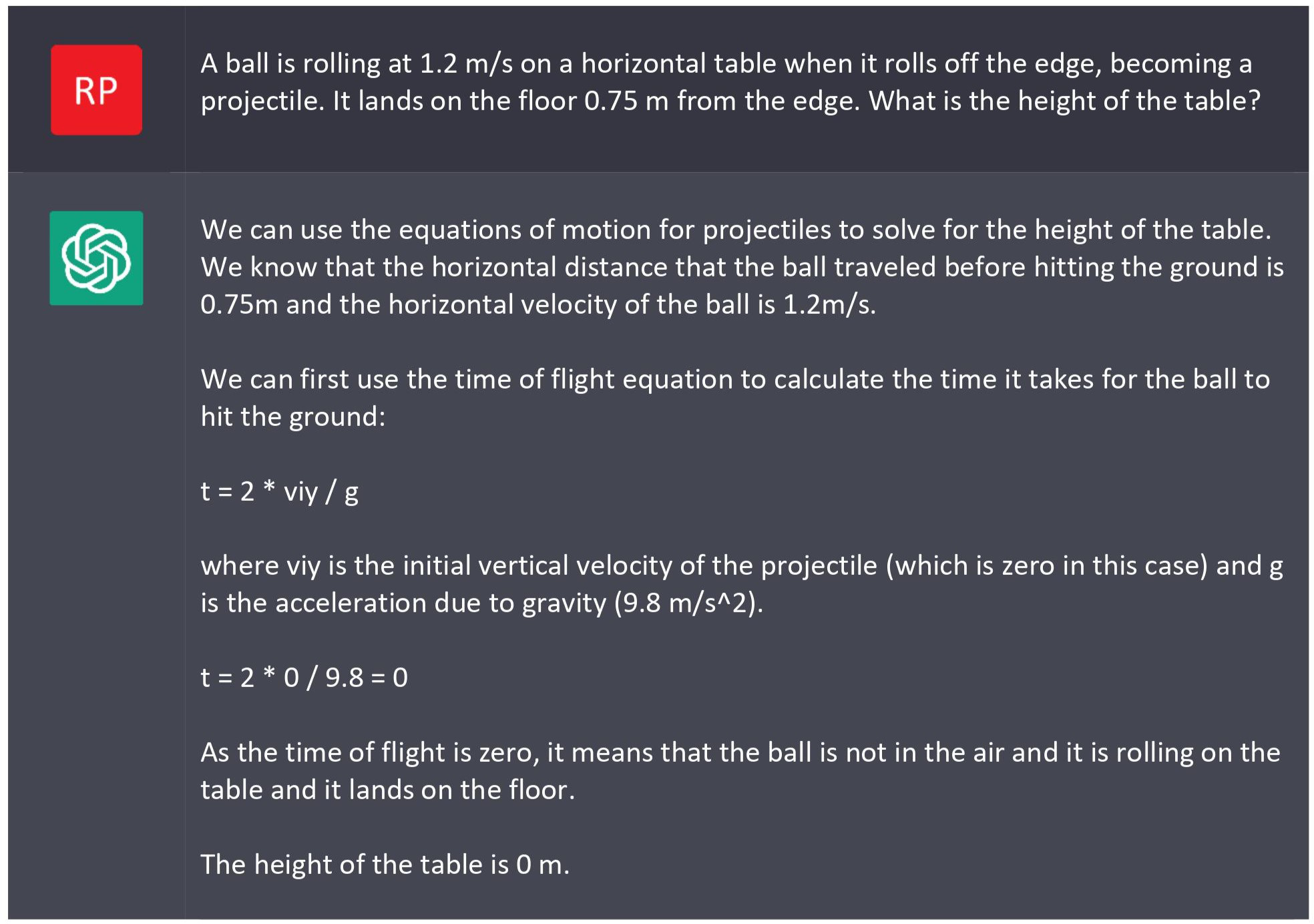

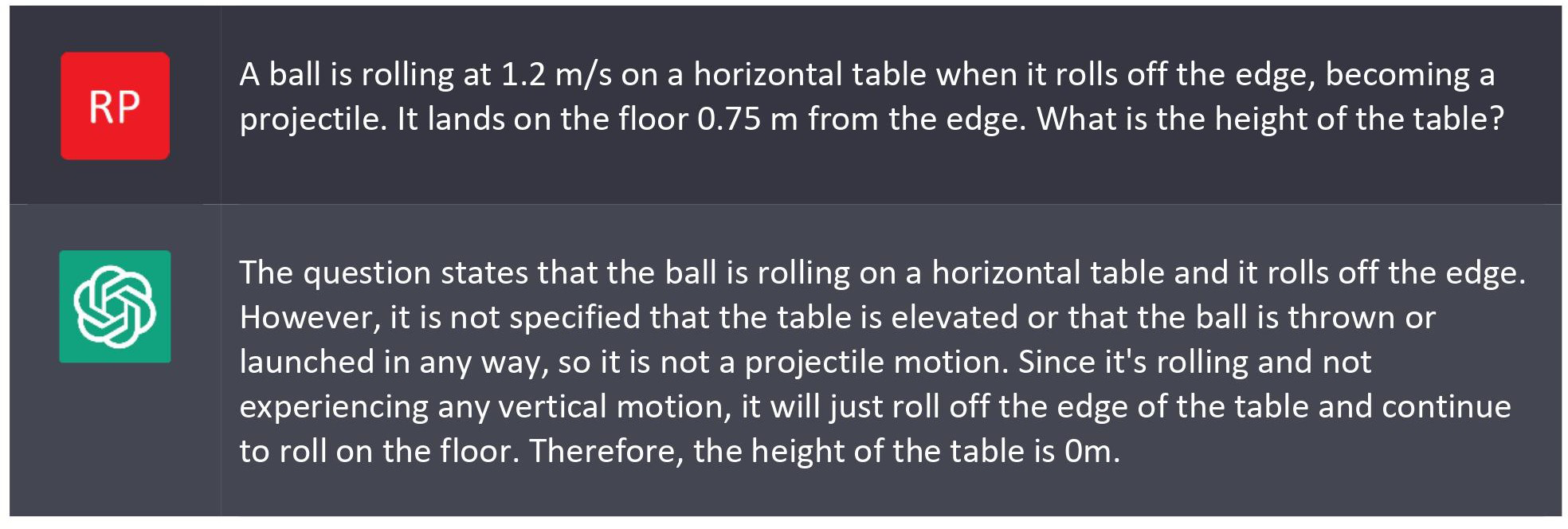

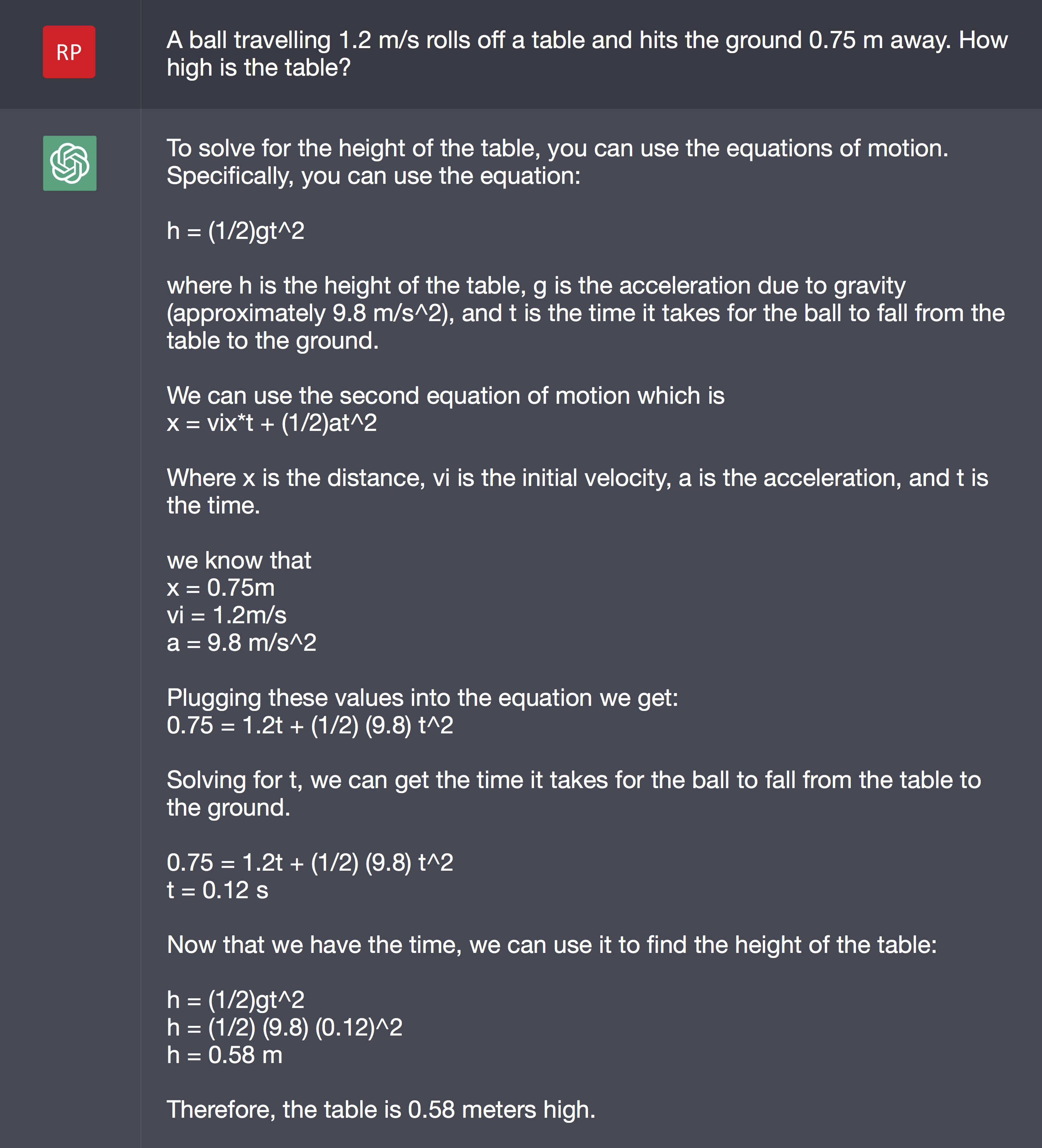

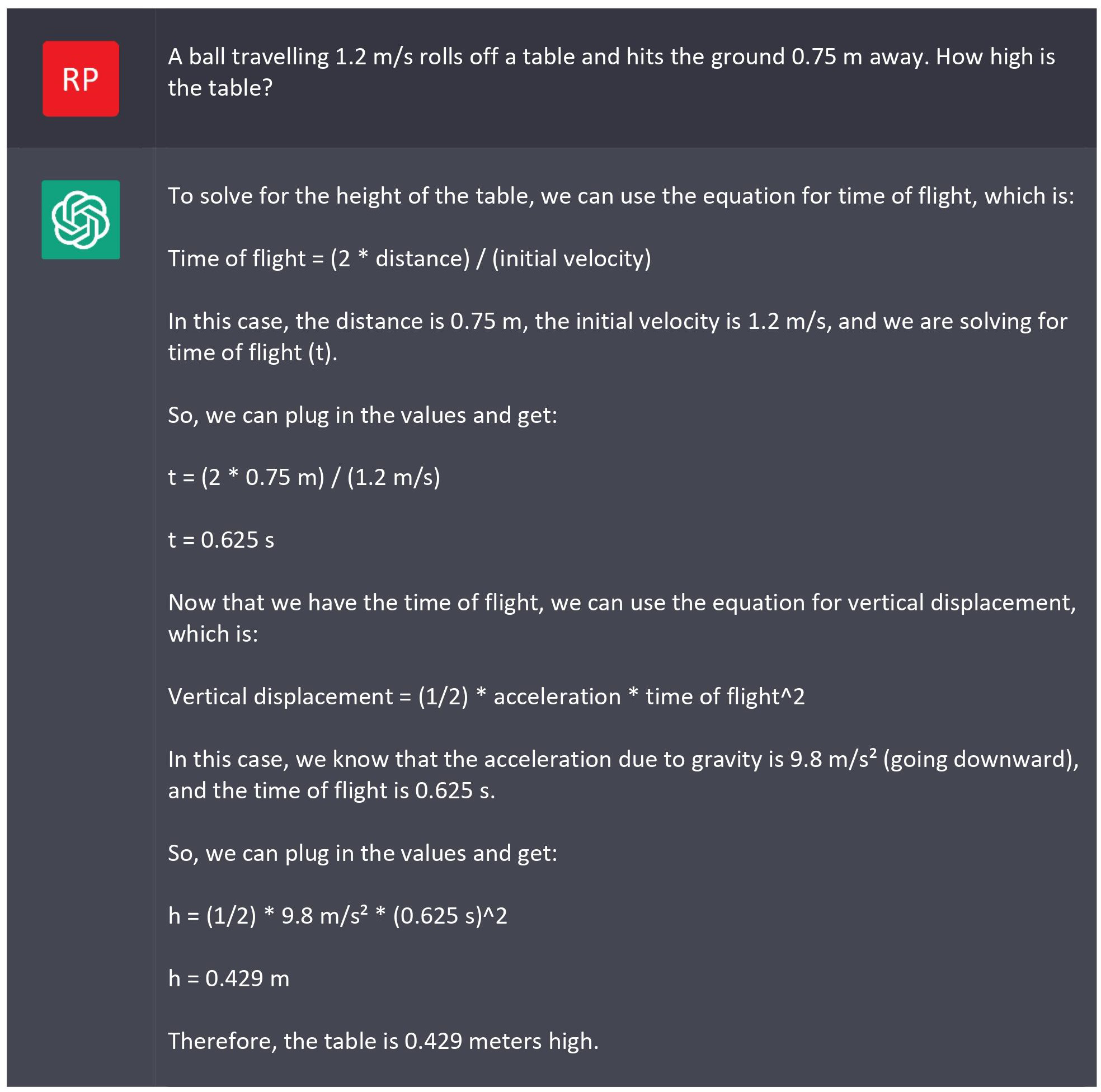

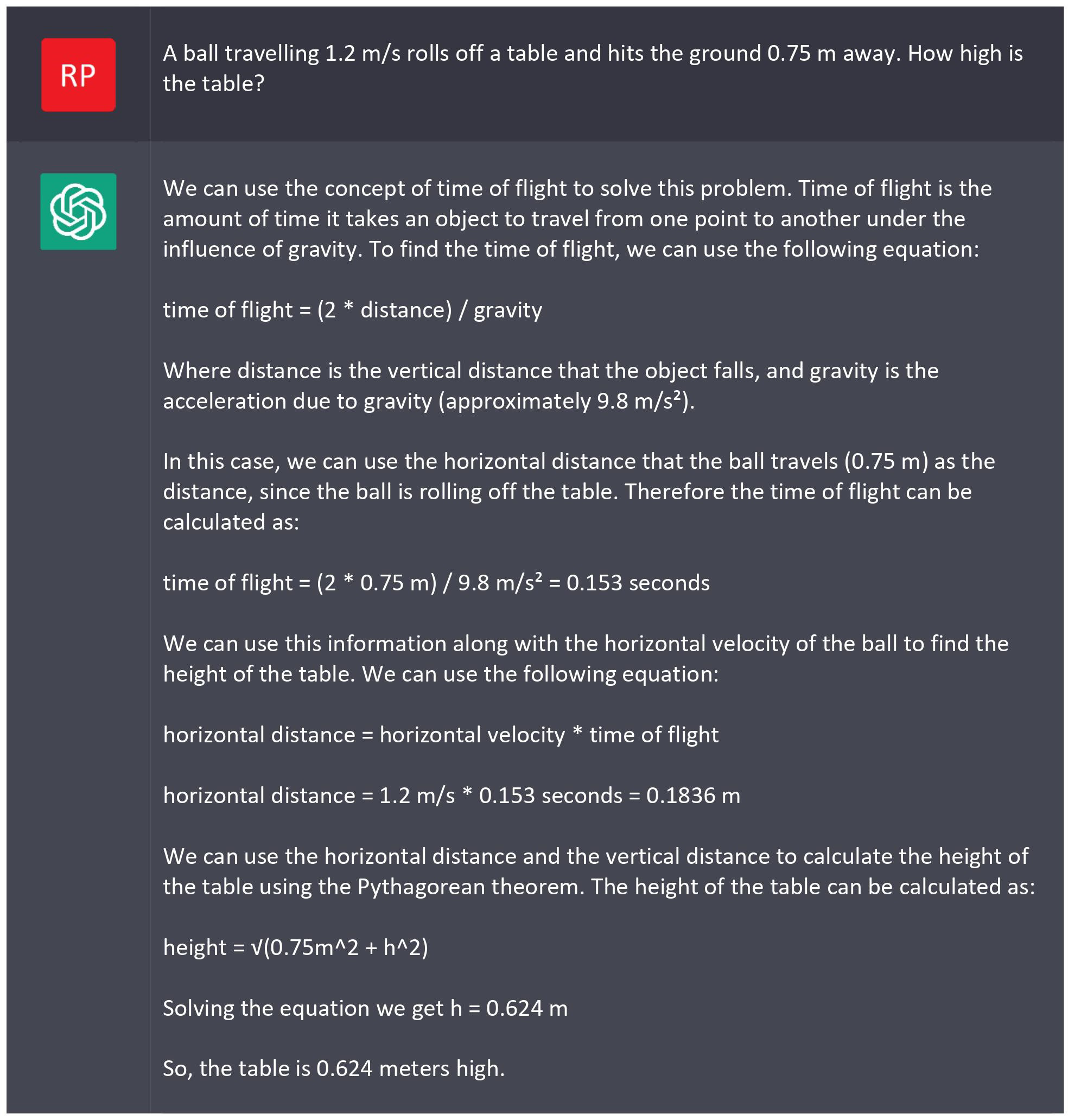

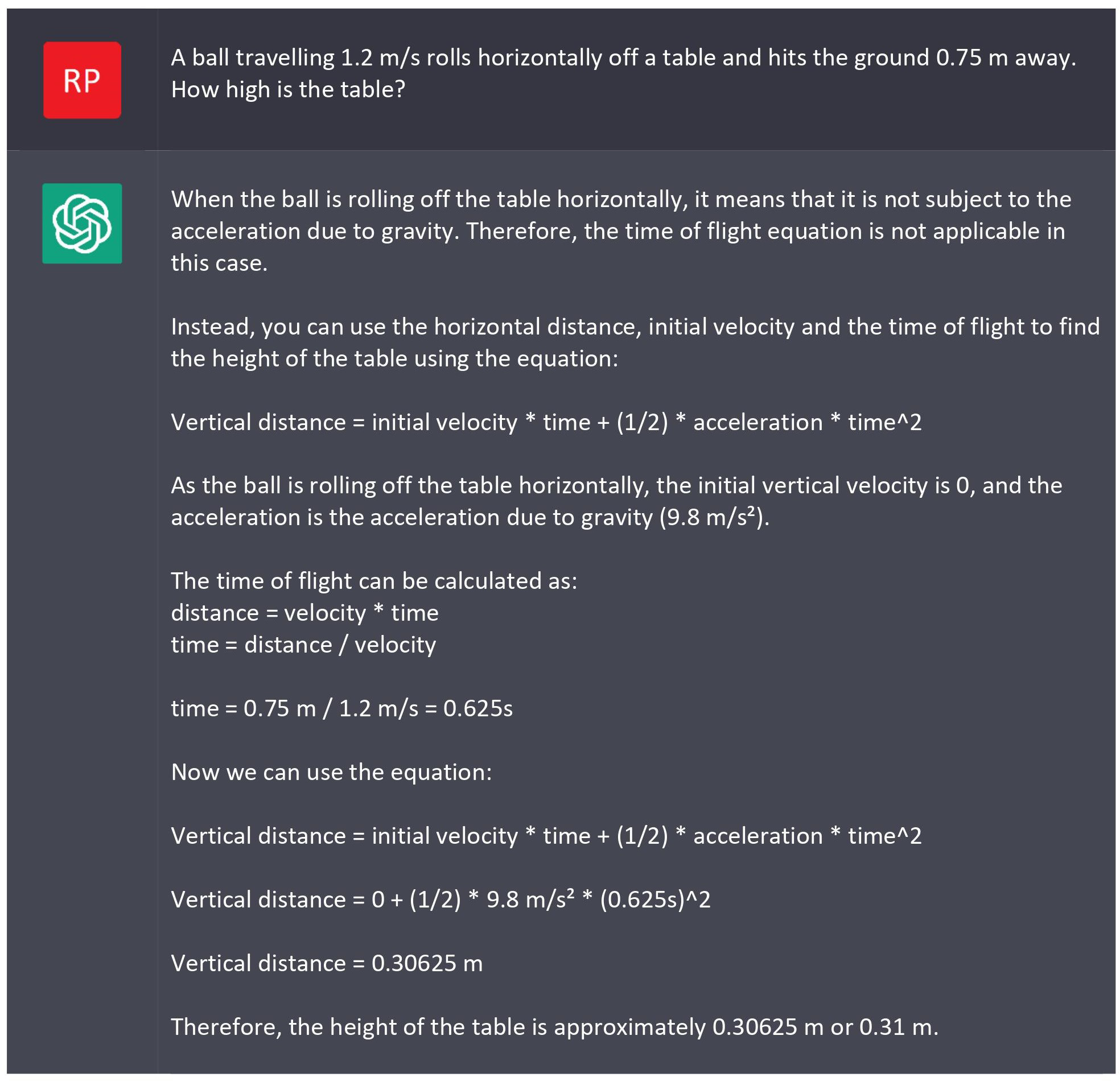

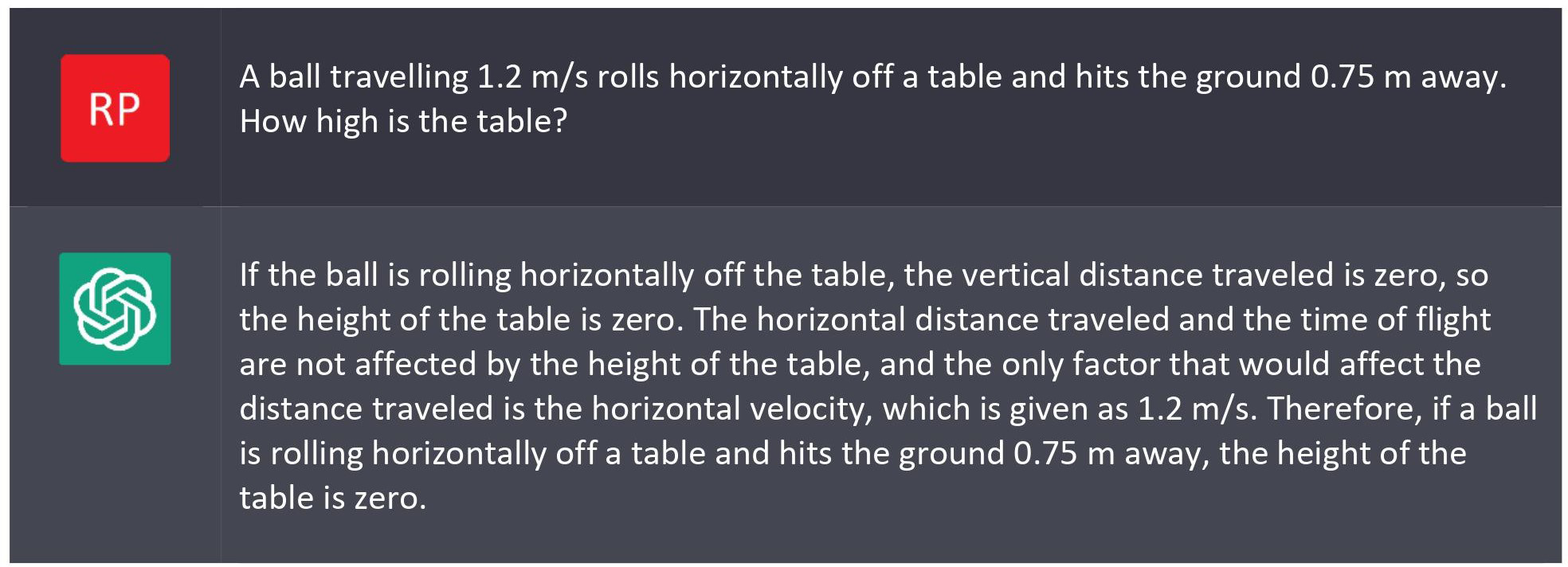

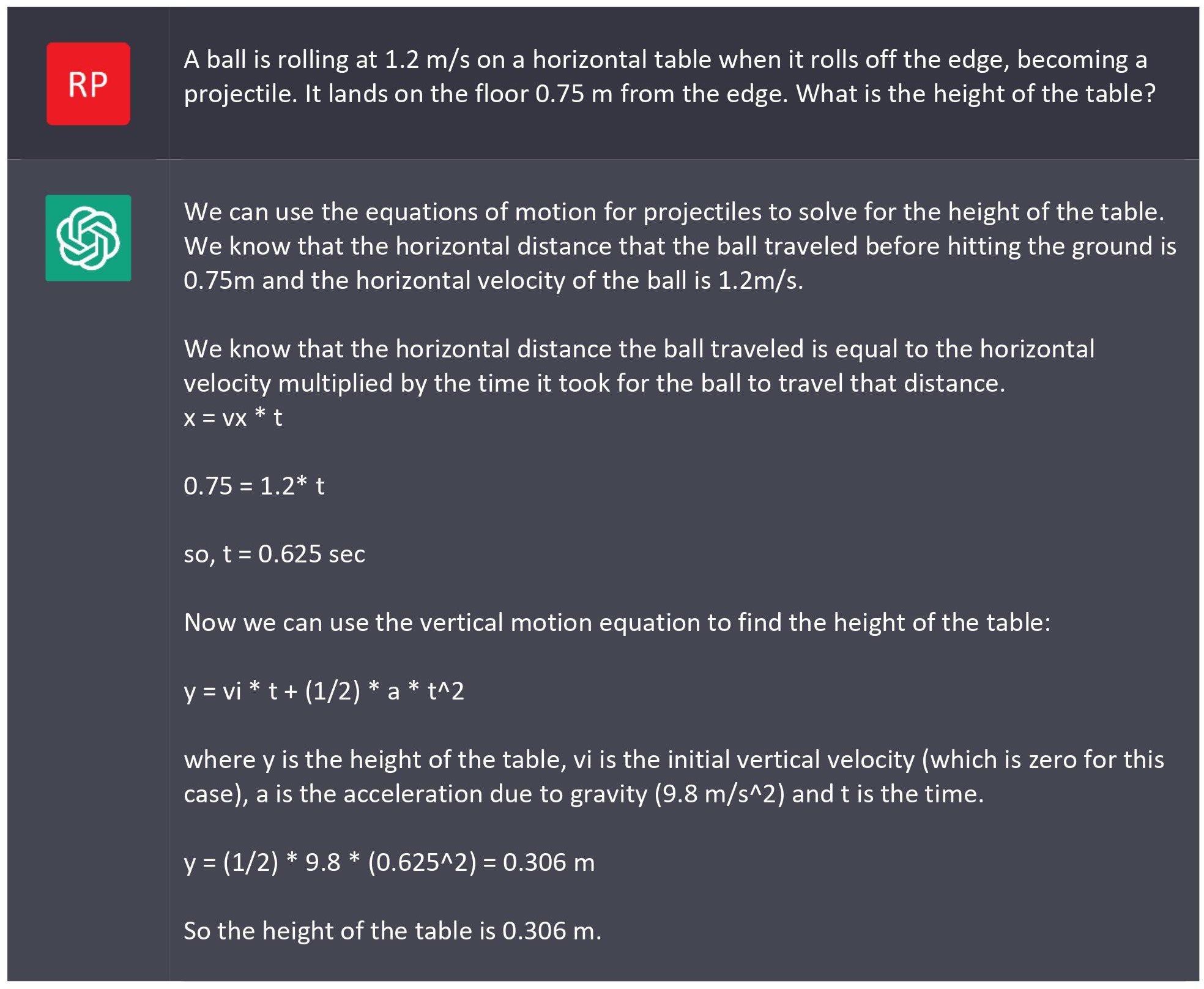

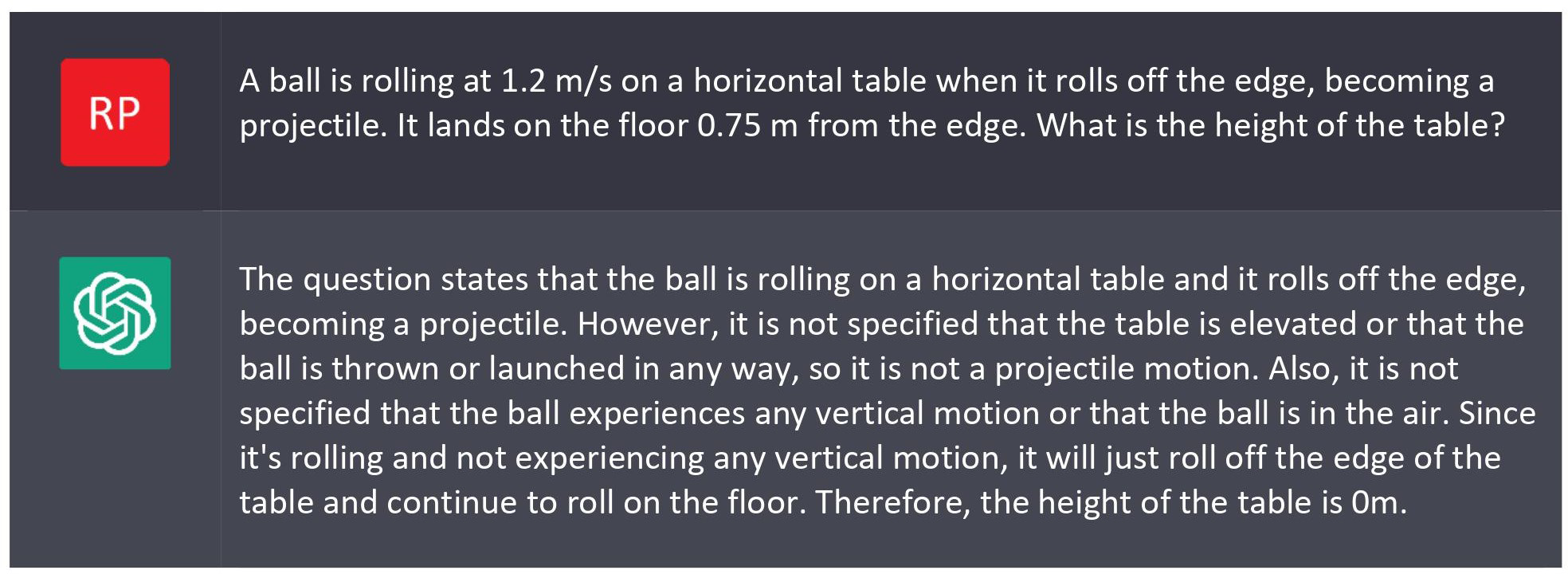

With reports that ChatGPT can actually mimic an operating system and debug computer code, it’s natural to wonder how well it handles physics problems. So I tried it out with a simple projectile problem. This problem includes some implicit information and assumptions, which ChatGPT struggled with.

Clearly the chatbot made some elementary mistakes!

I regenerated the response (see

Appendix 2) and got several different answers.

- (Incorrect) explanation but no solution.

- The table is 0.153 meters high.

- Therefore, the table is 0.429 meters high.

- So, the table is 0.624 meters high.

- Therefore, the height of the table is approximately 3.0625 m or 3.06 m.

- 6.15 m

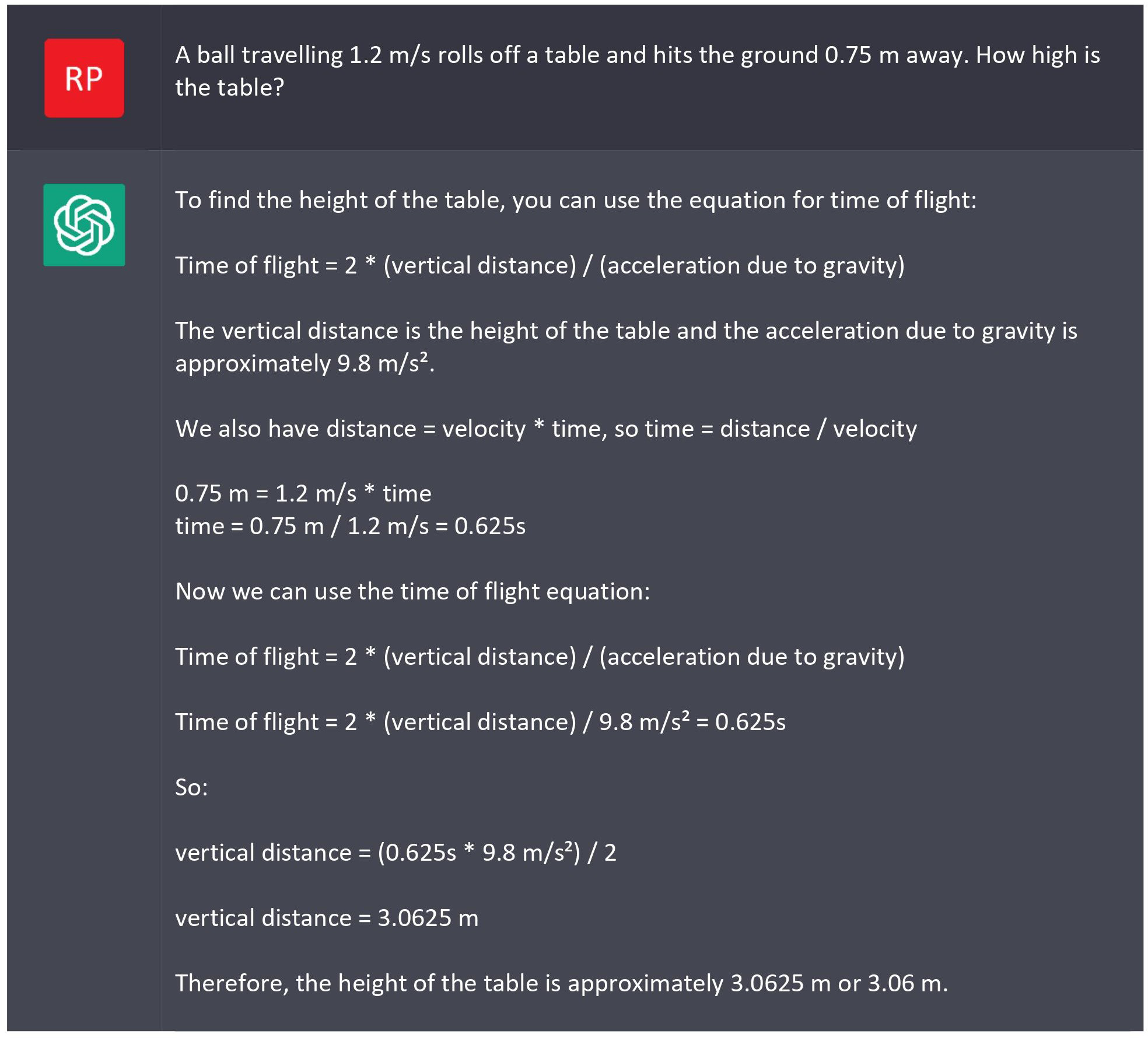

Seven responses, seven different answers. ChatGPT resembles a student looking through their equations trying to find one that fits, and plugging in numbers, rather than one who actually understands what is going on.

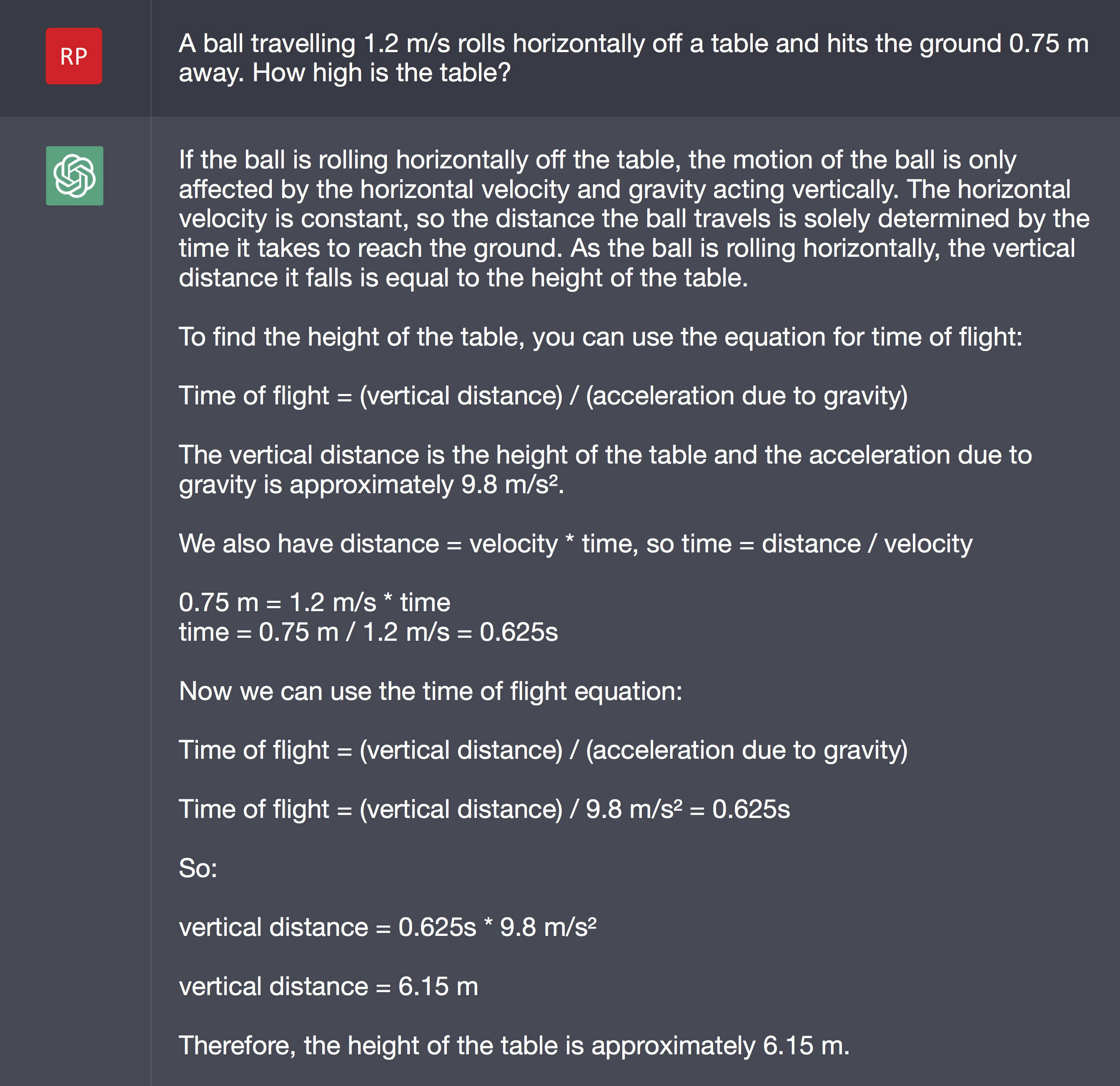

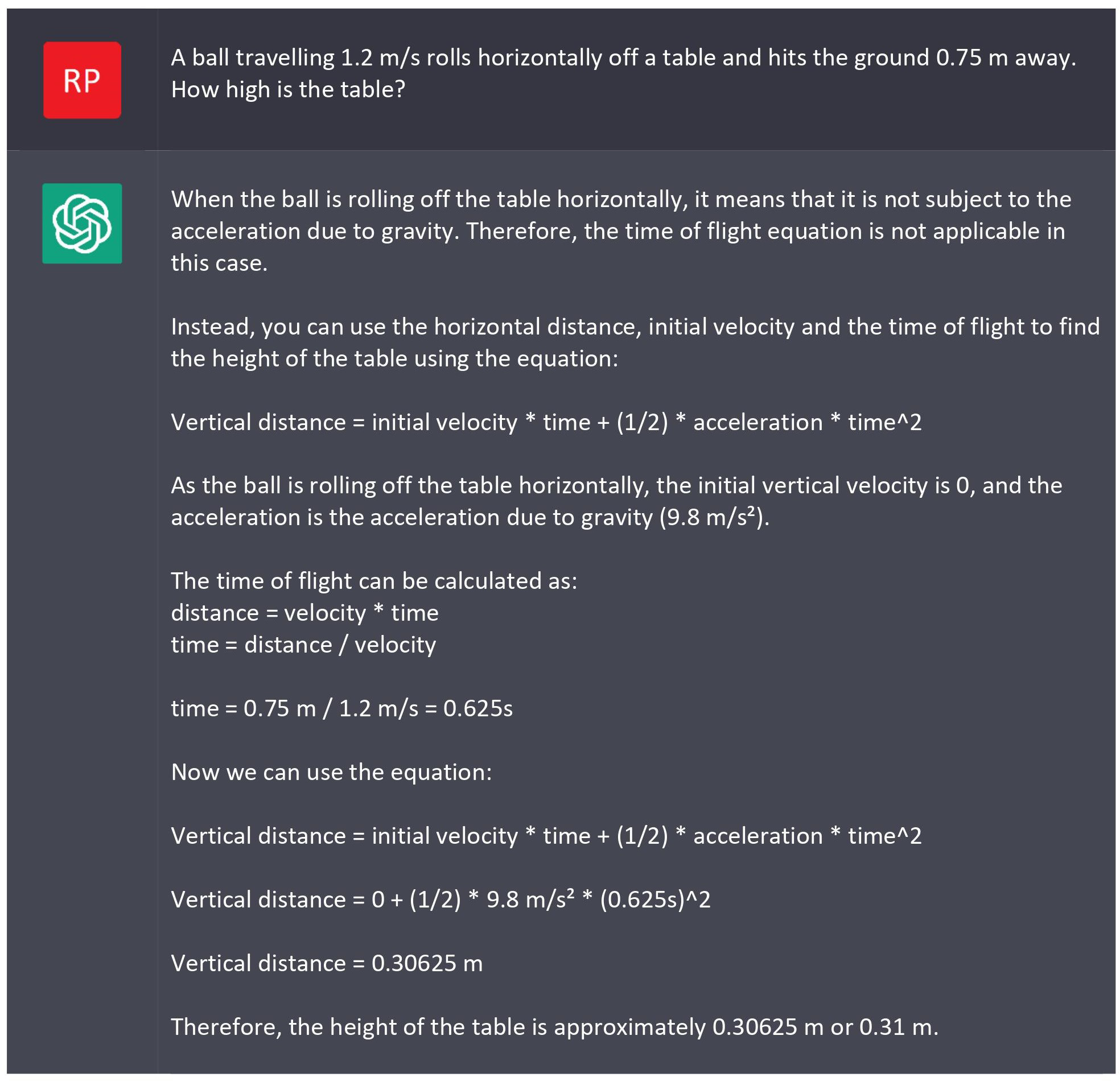

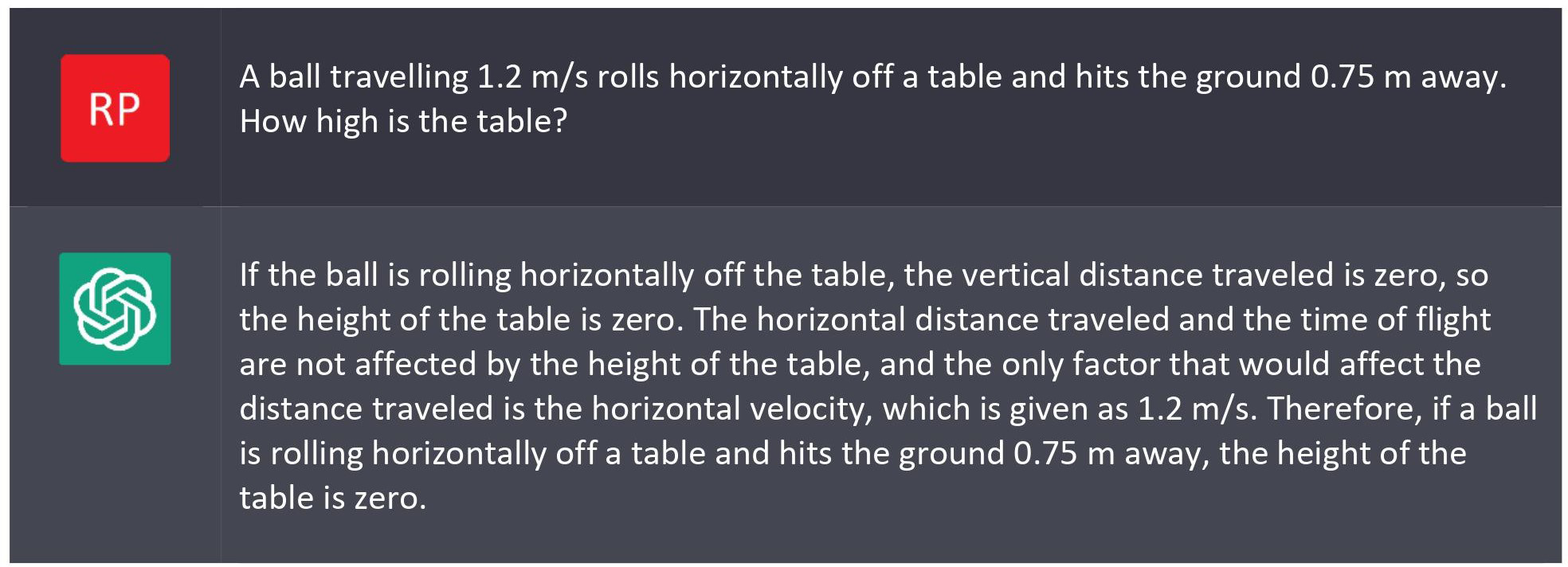

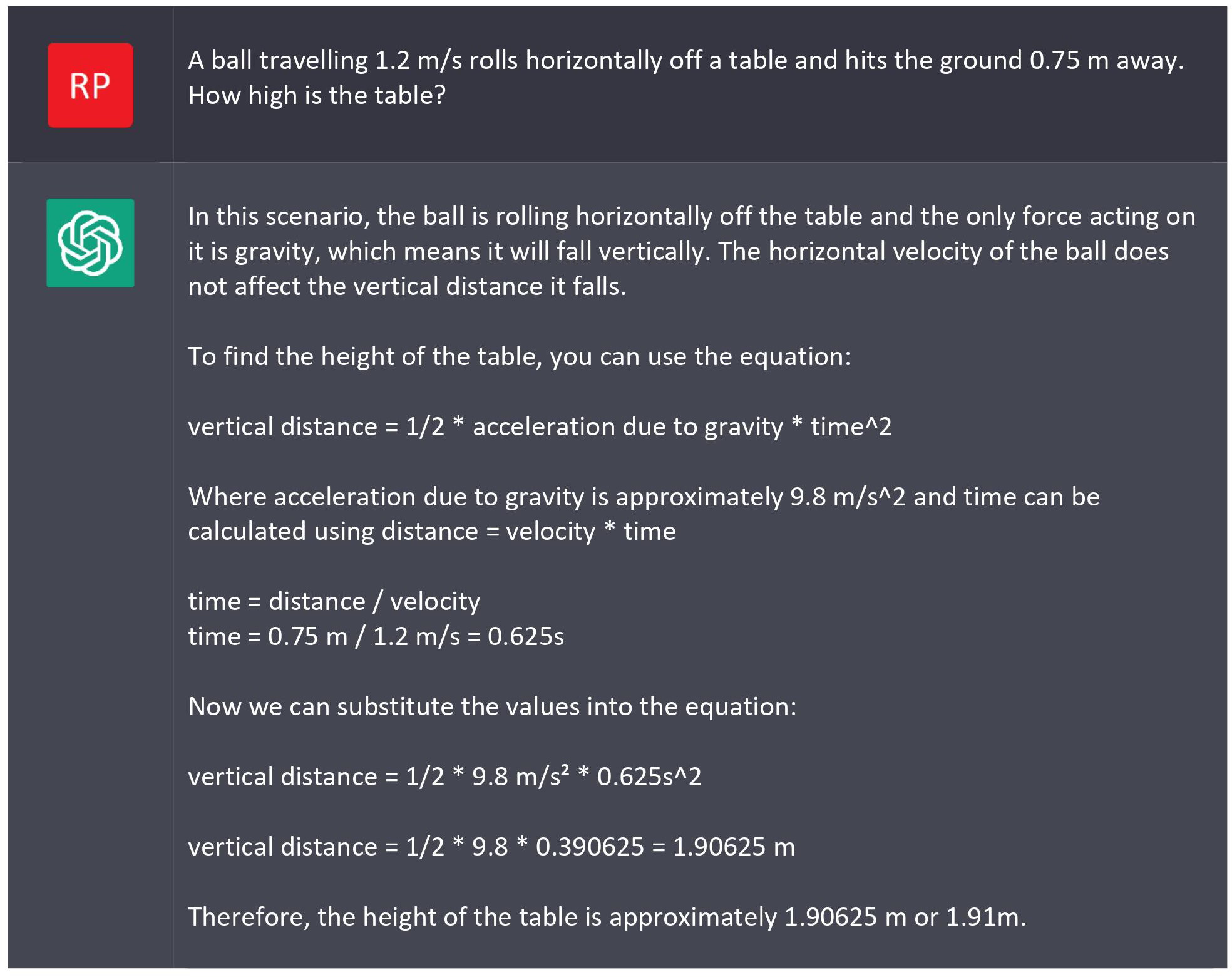

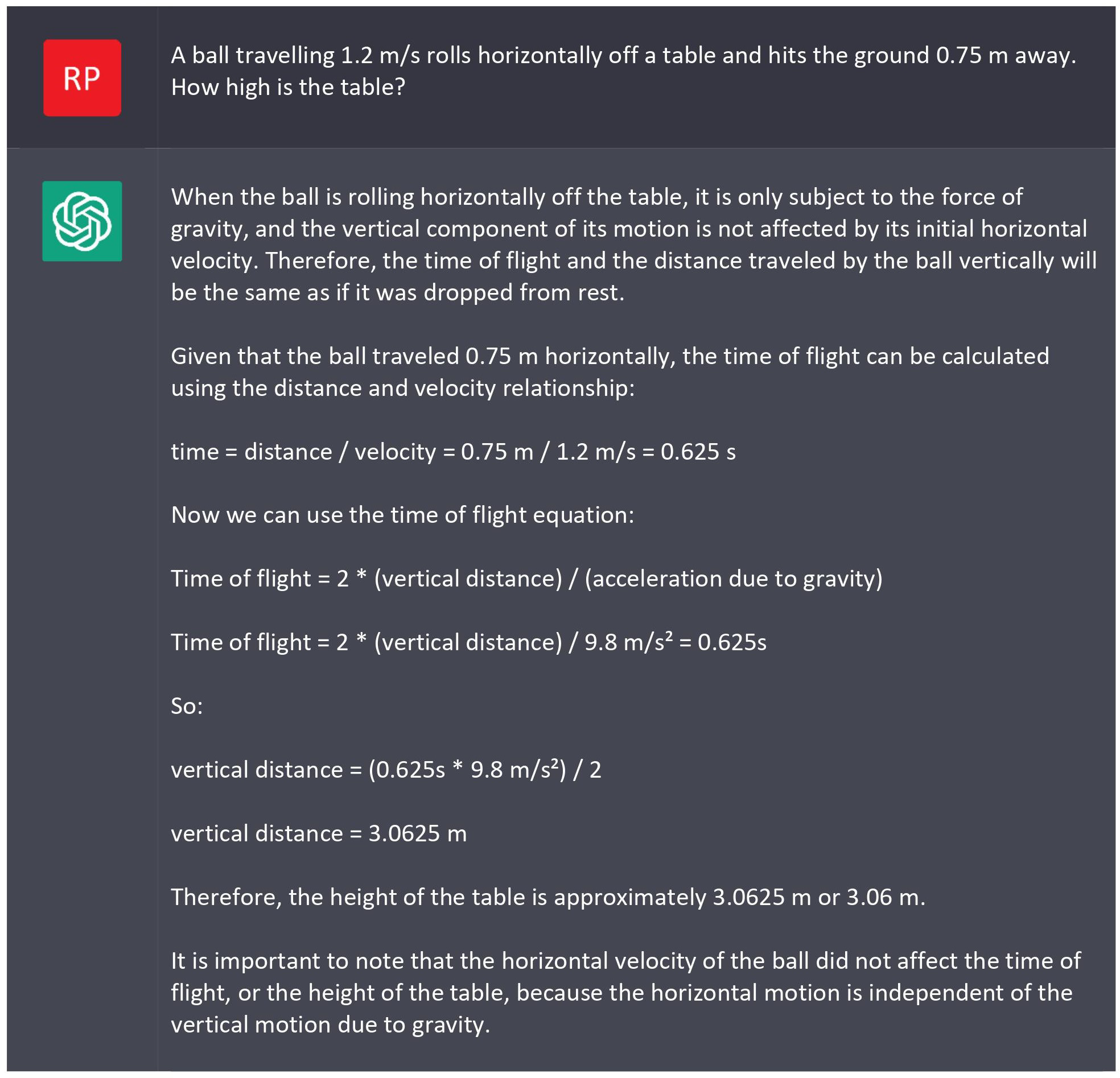

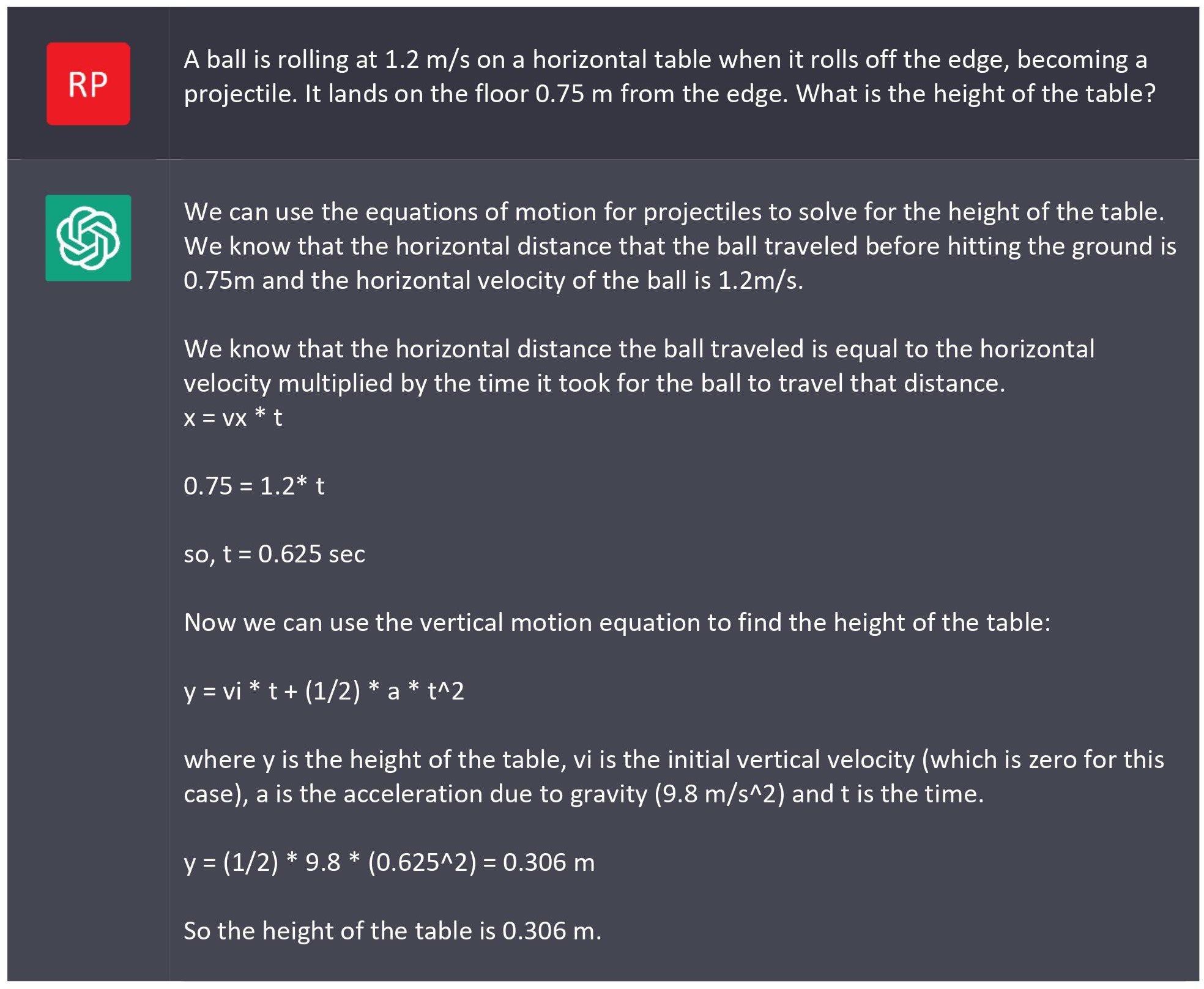

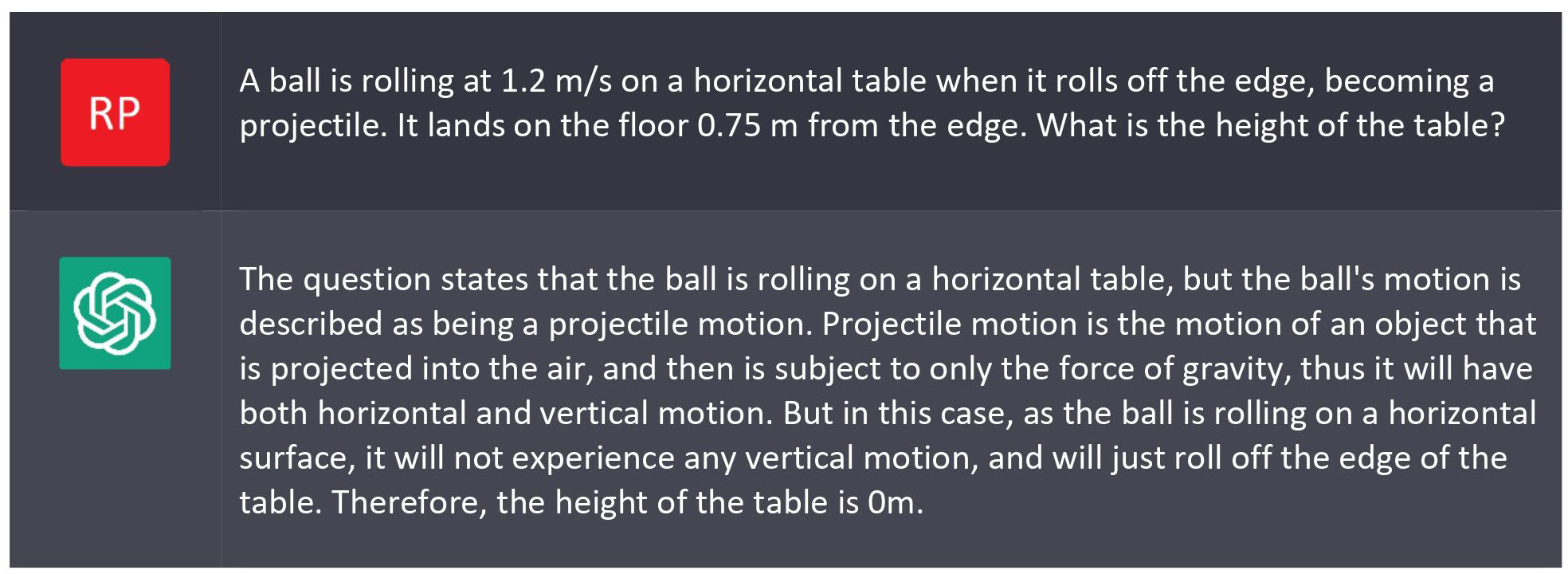

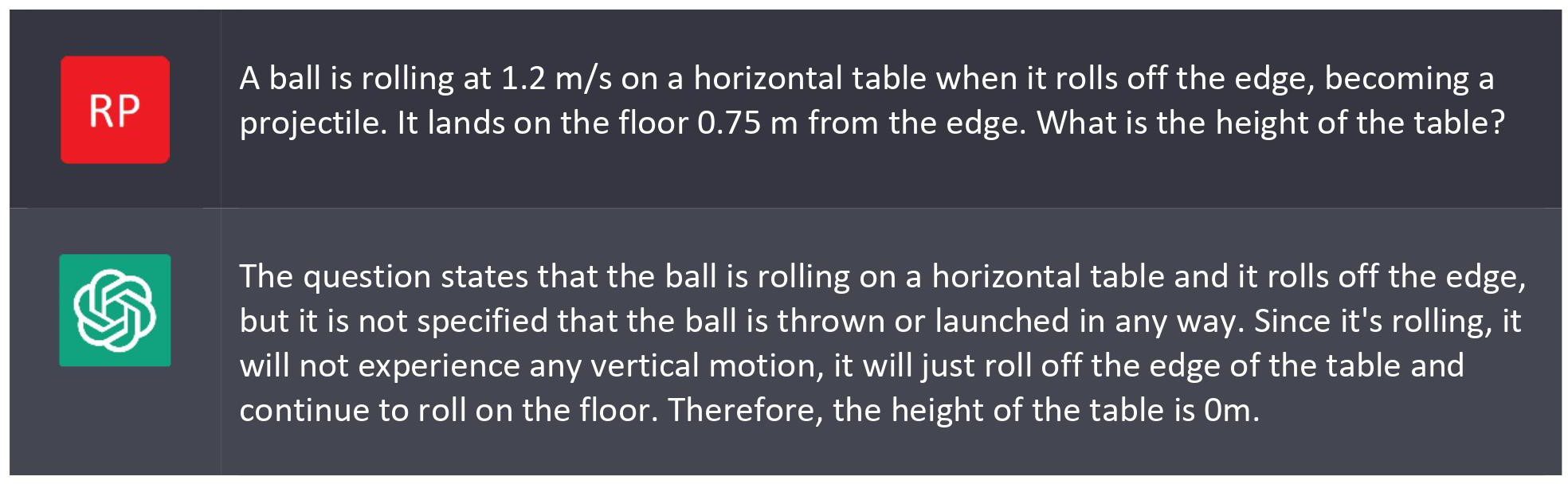

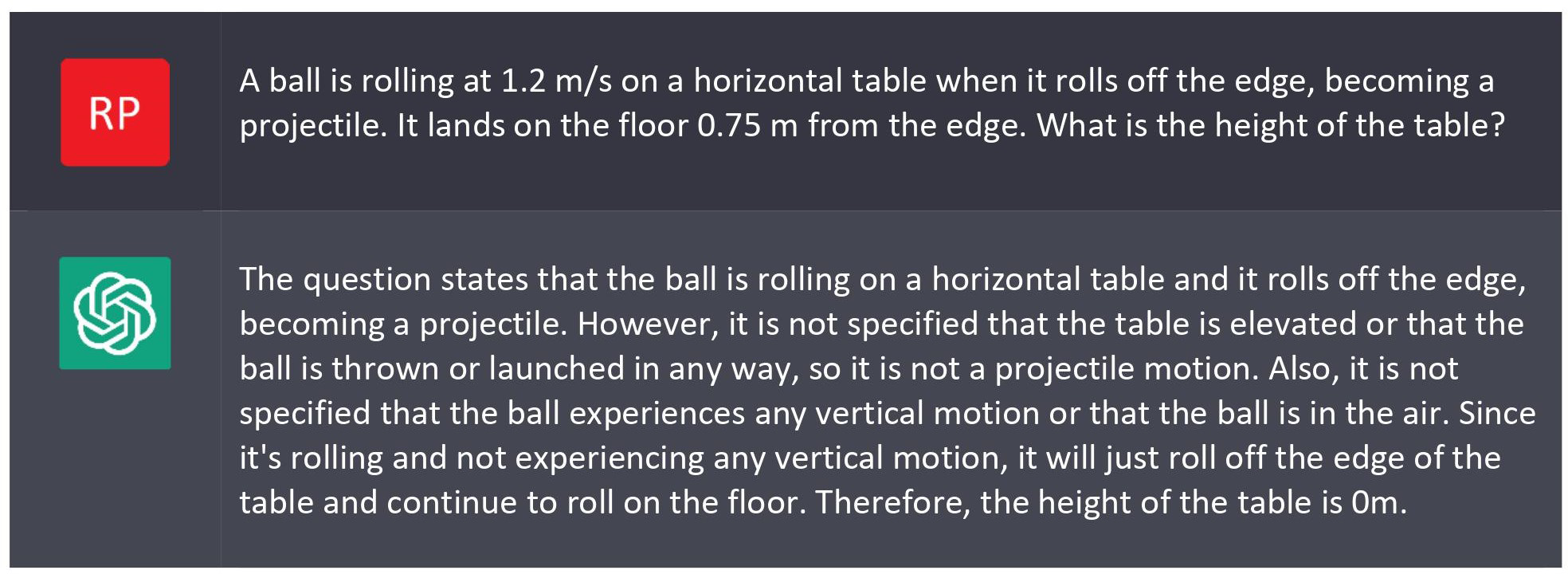

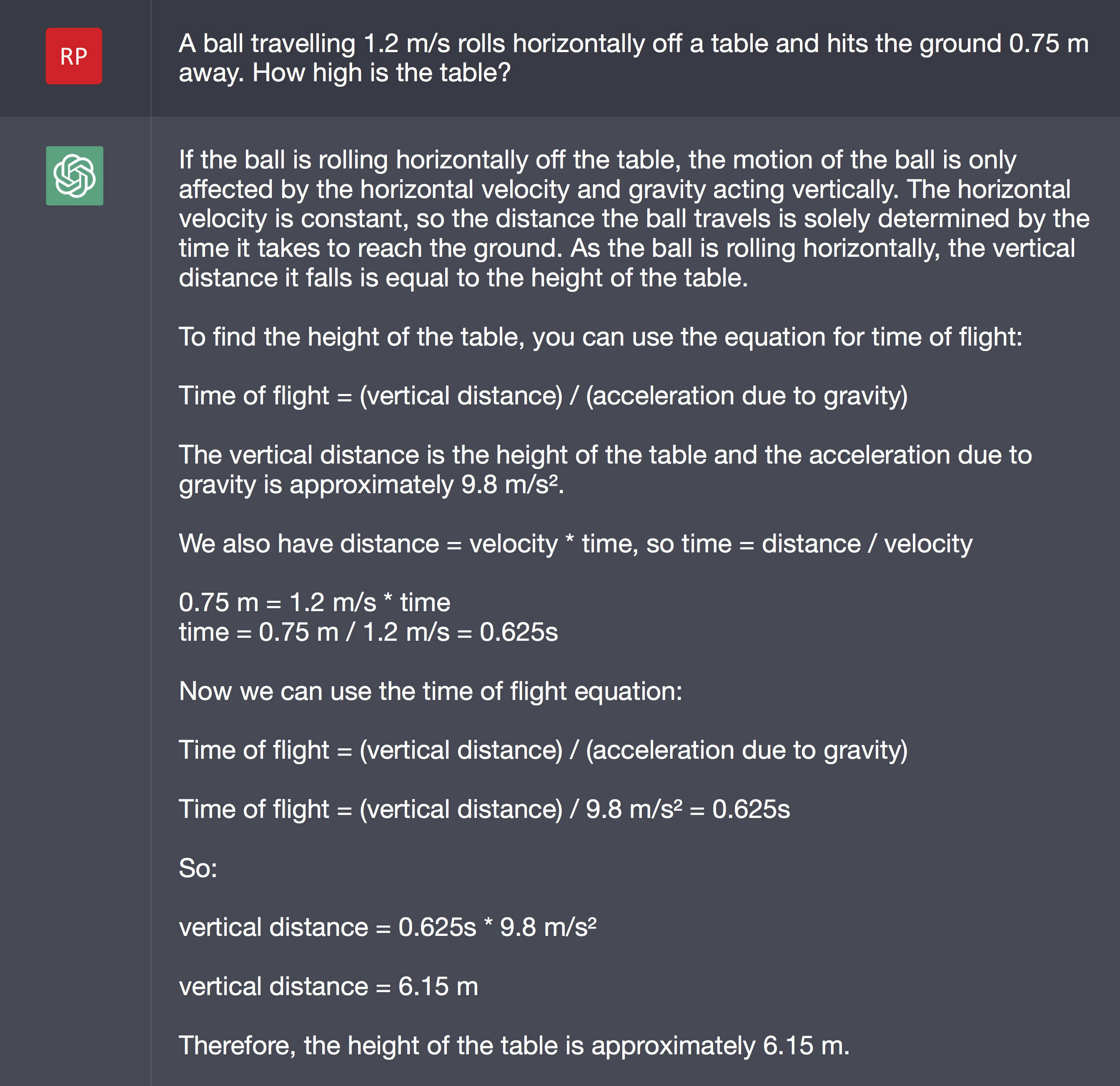

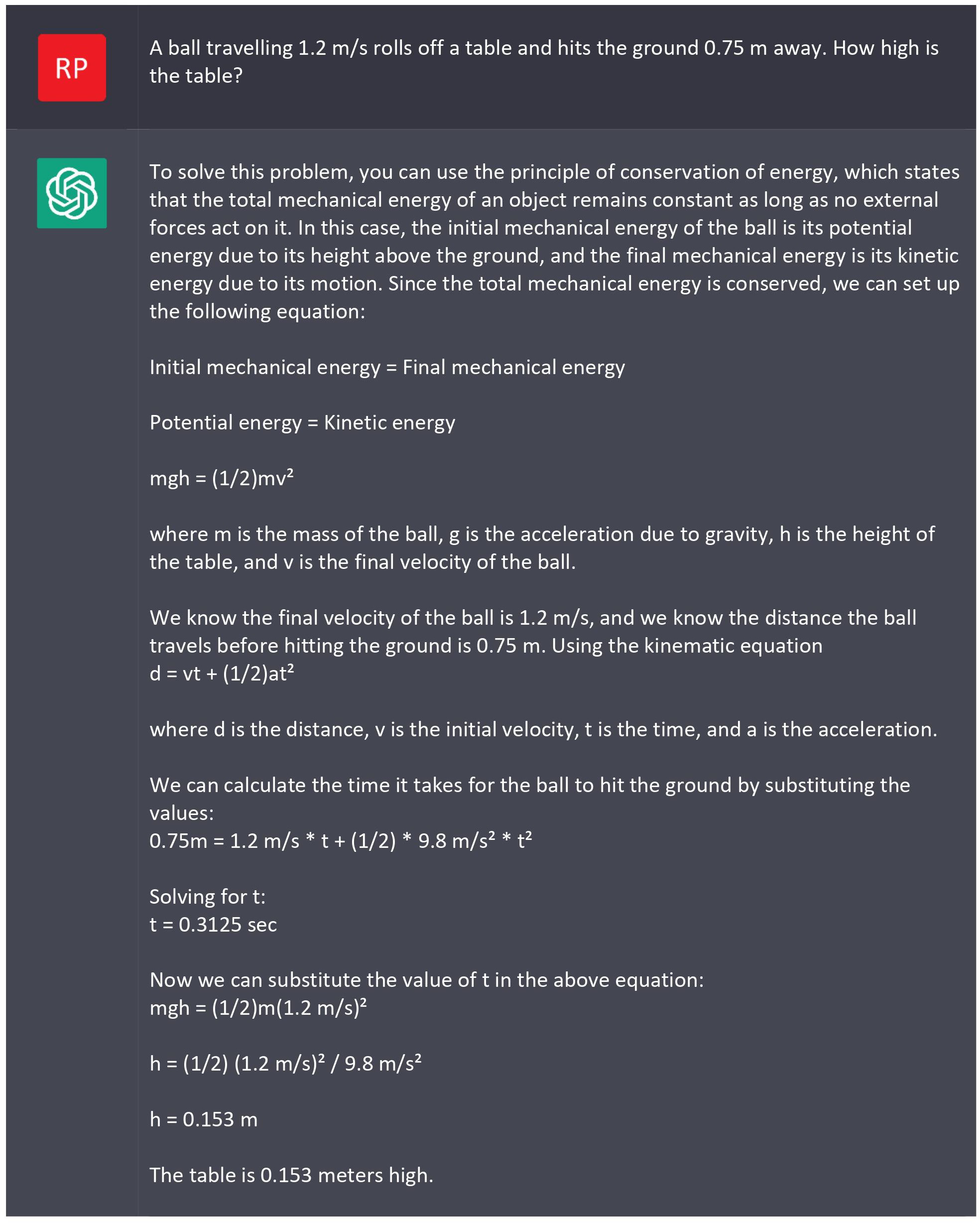

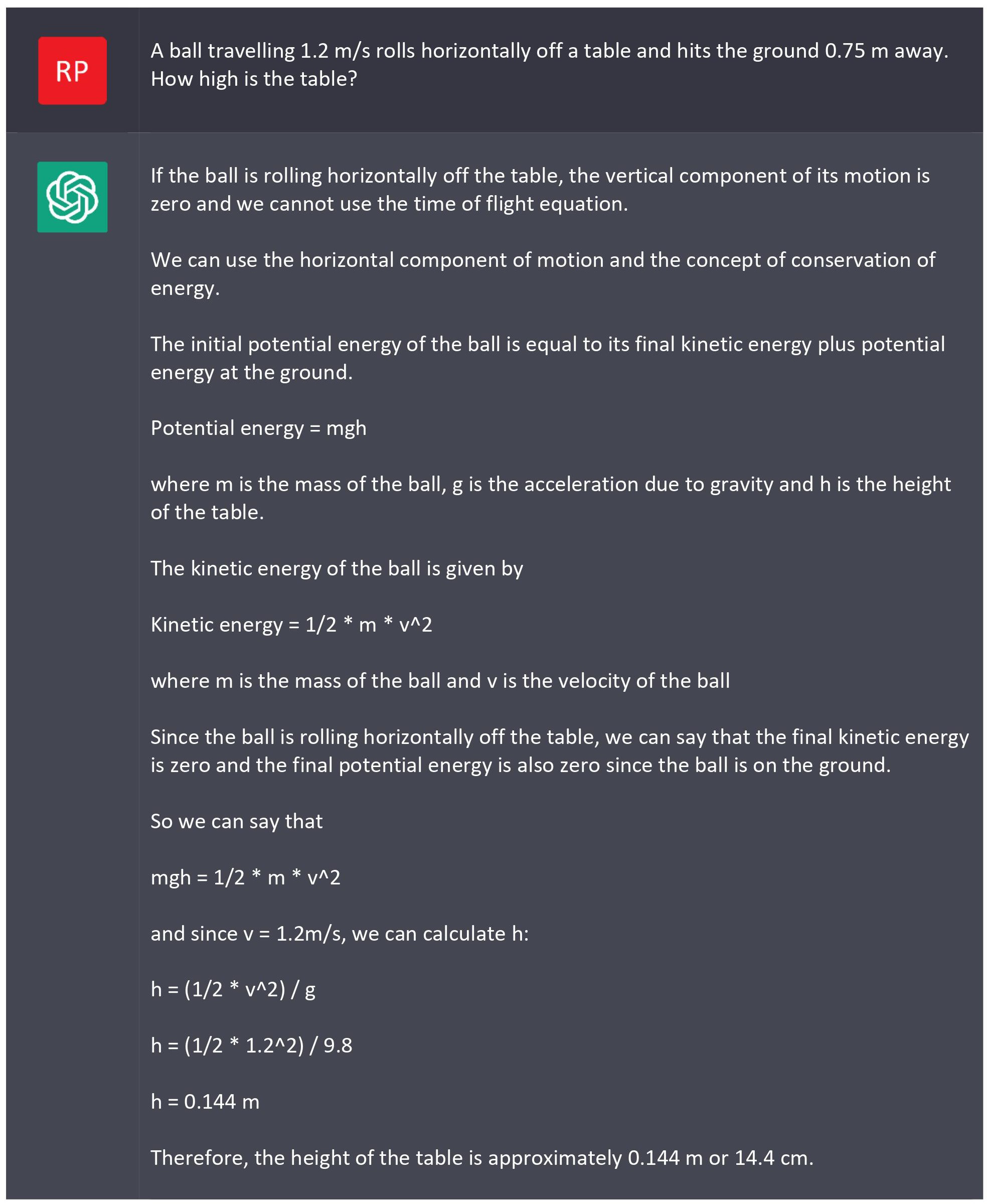

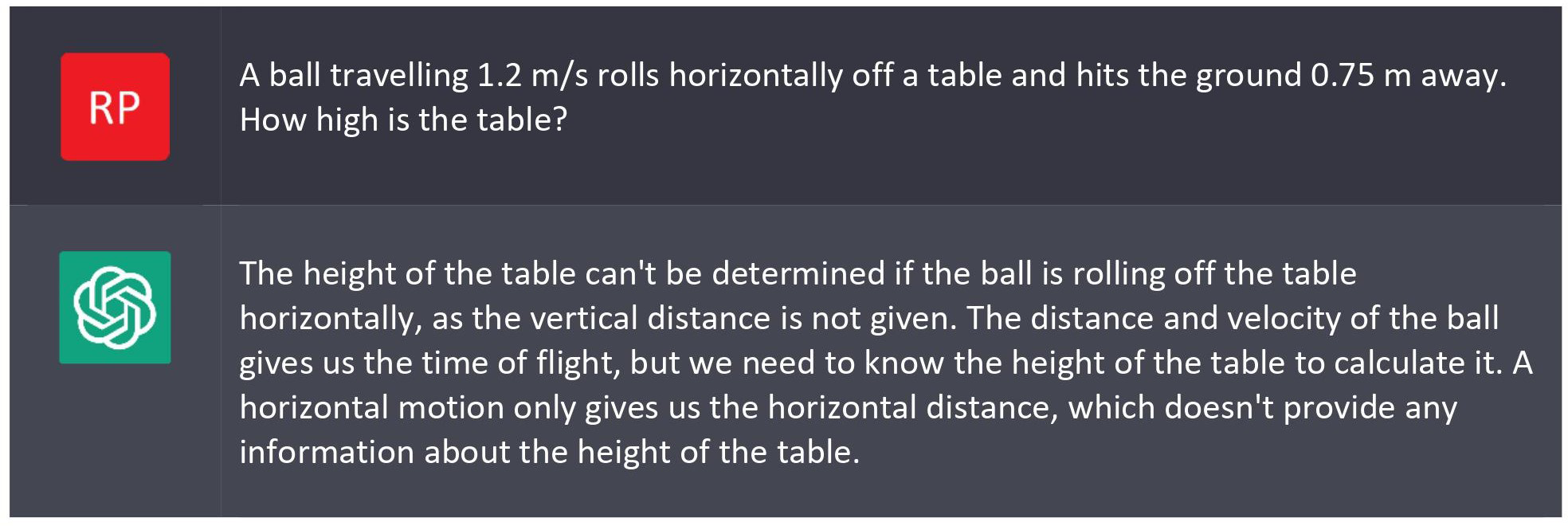

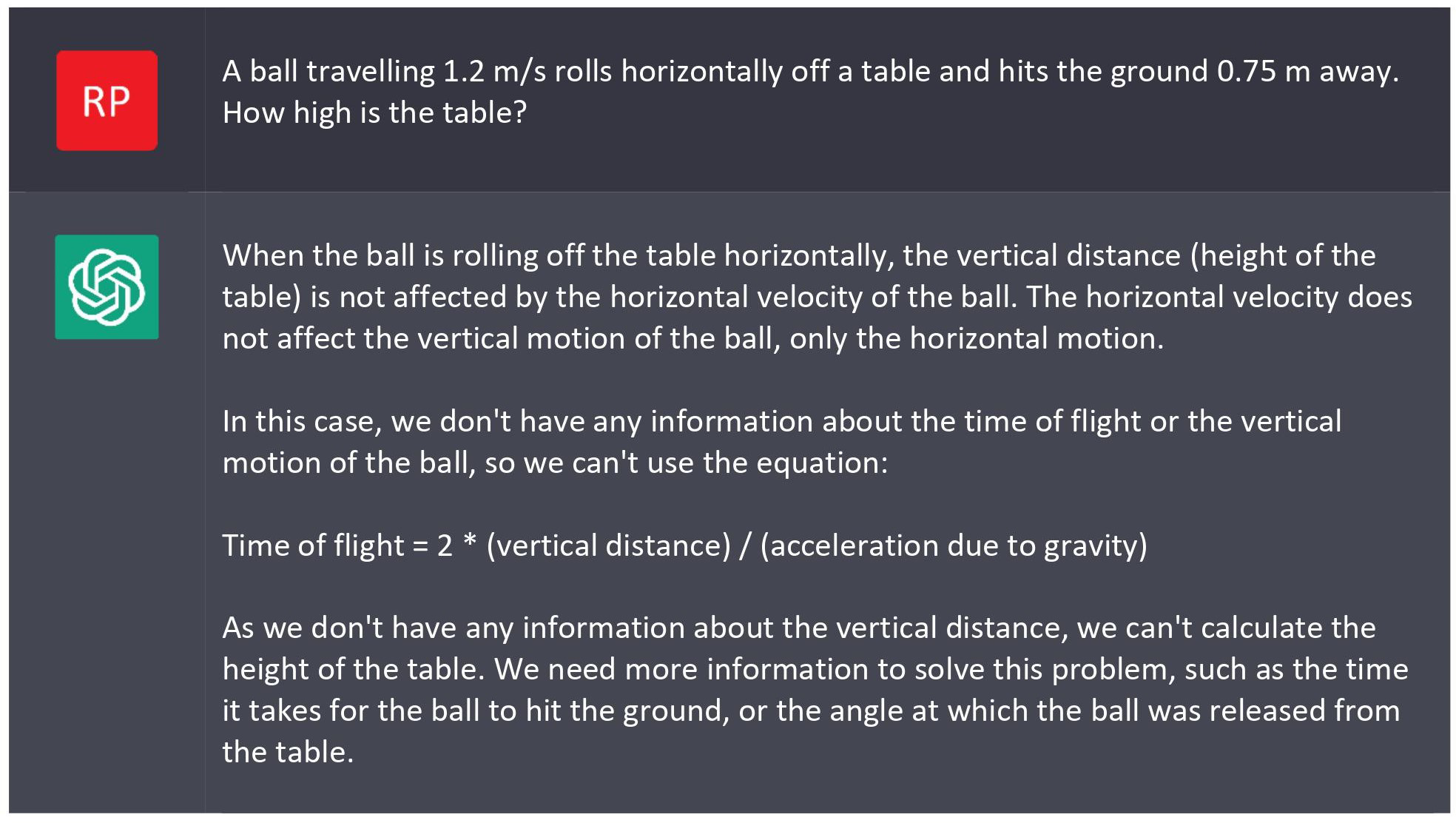

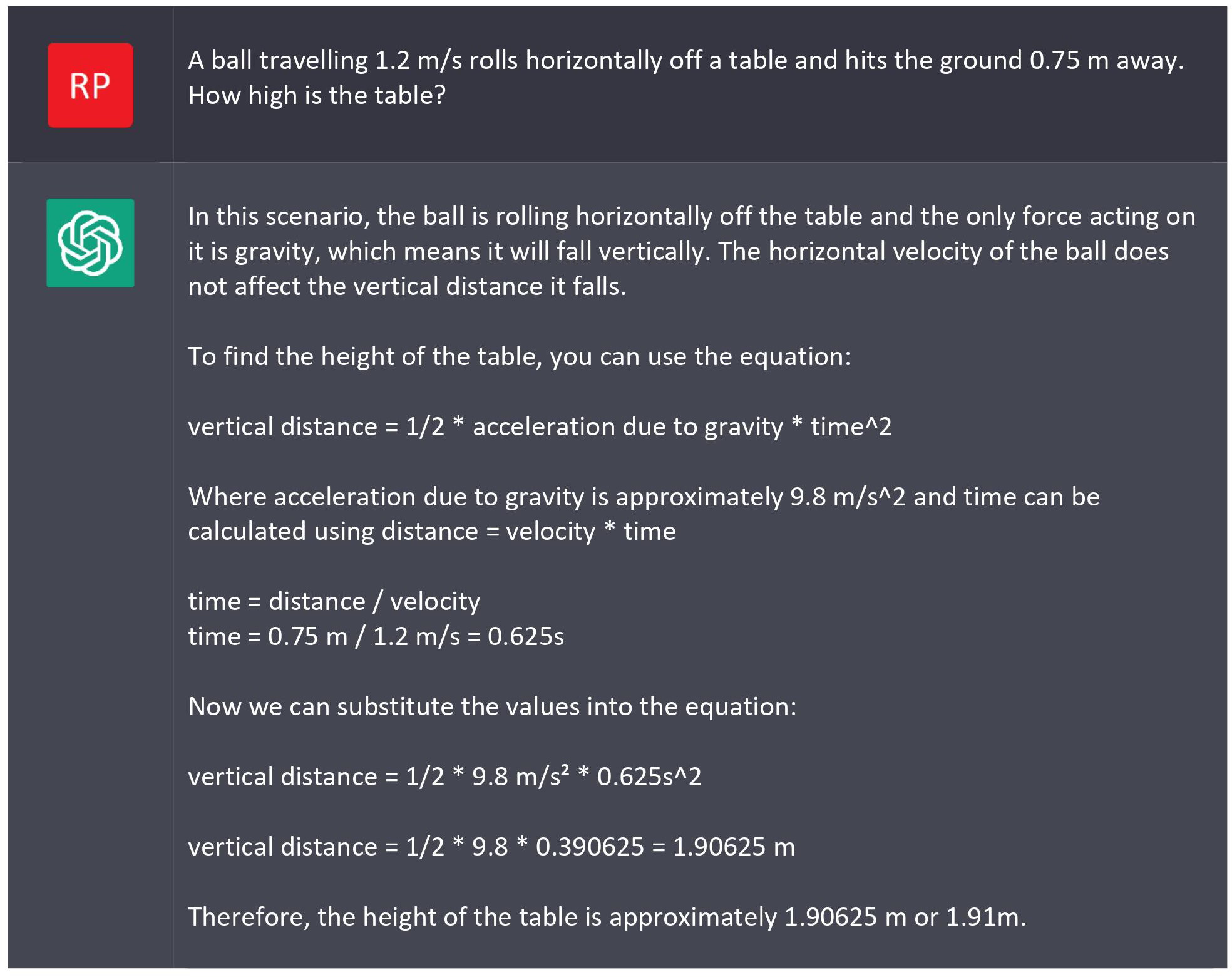

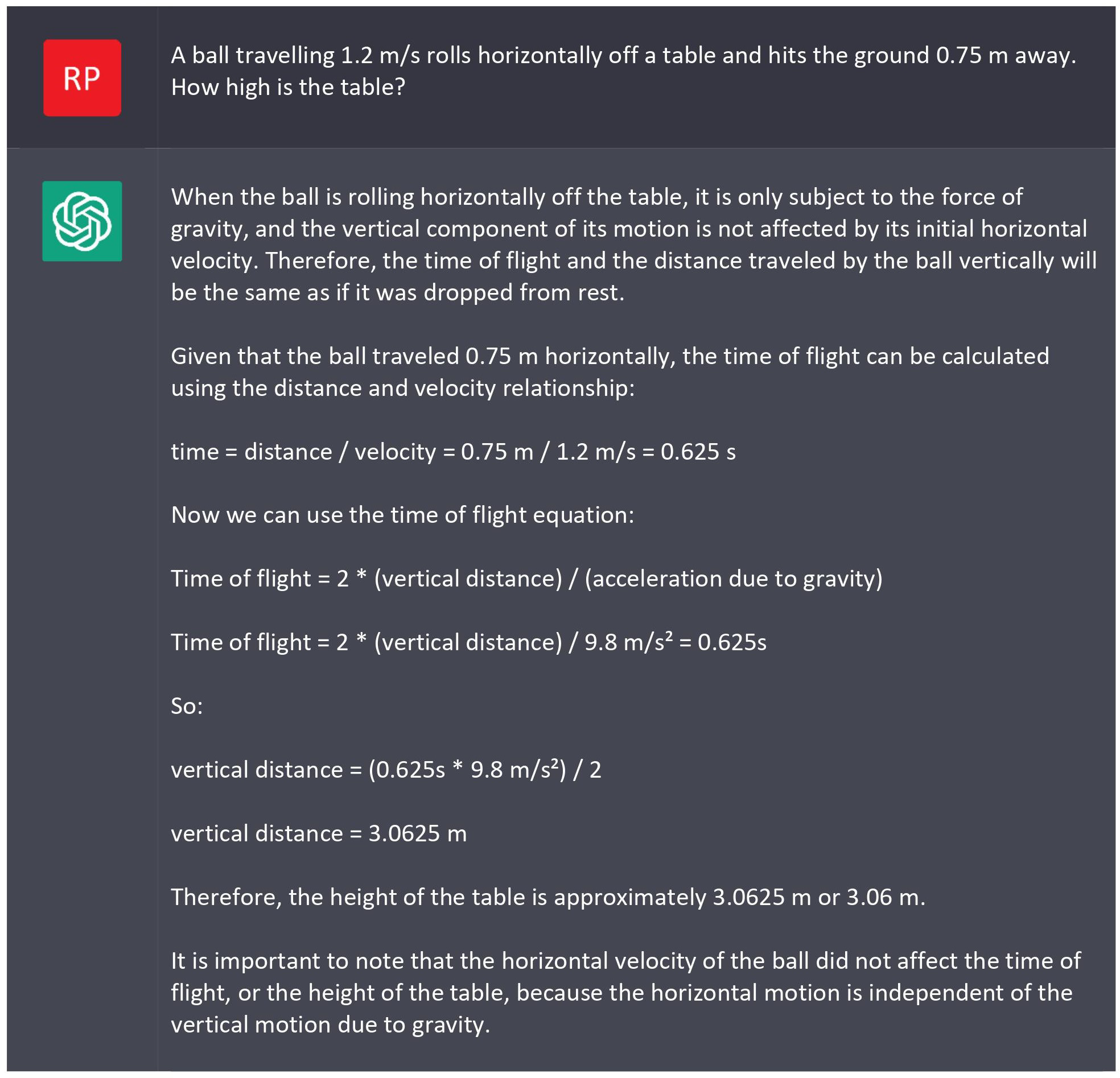

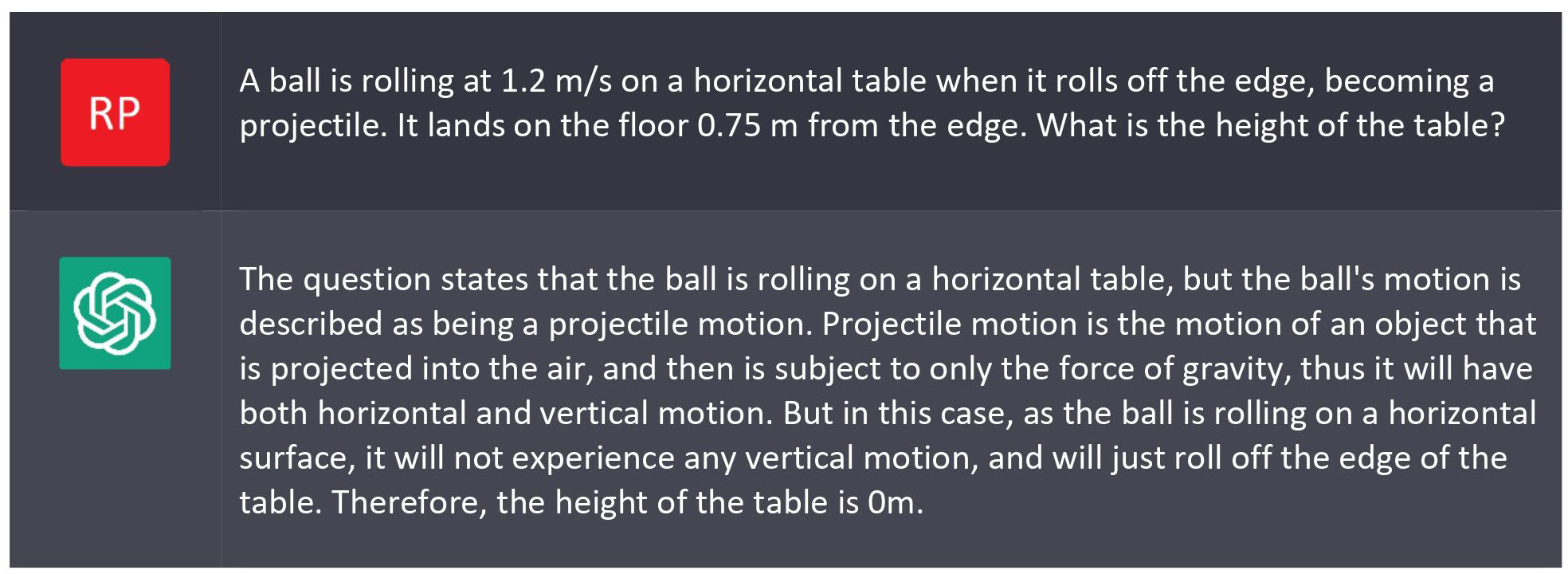

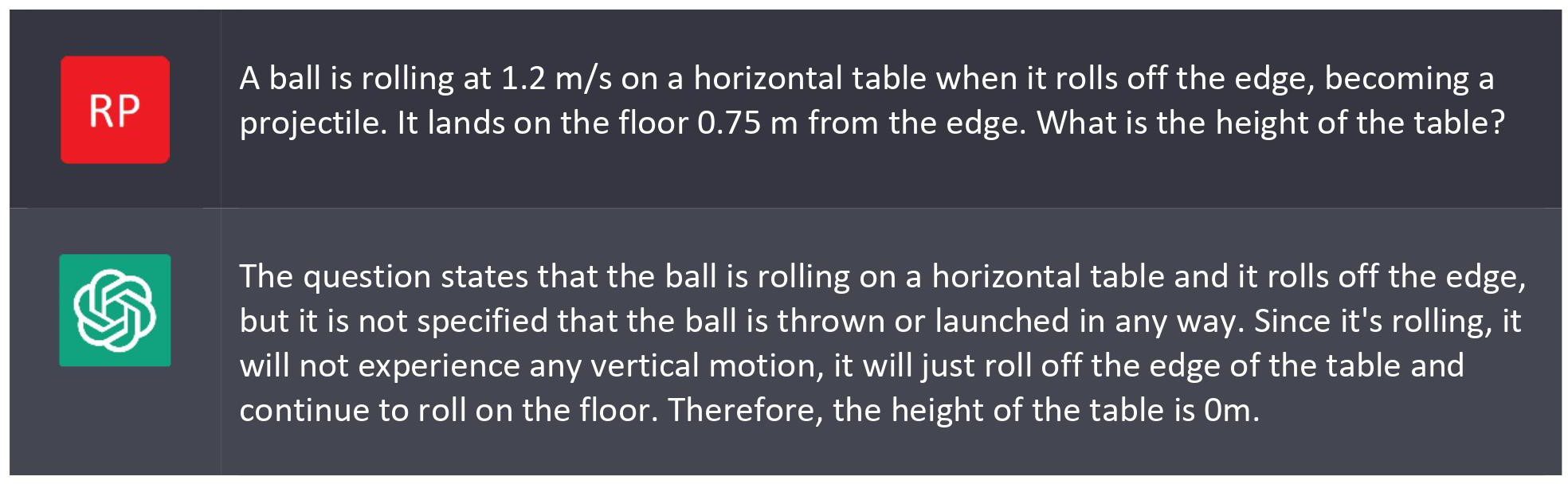

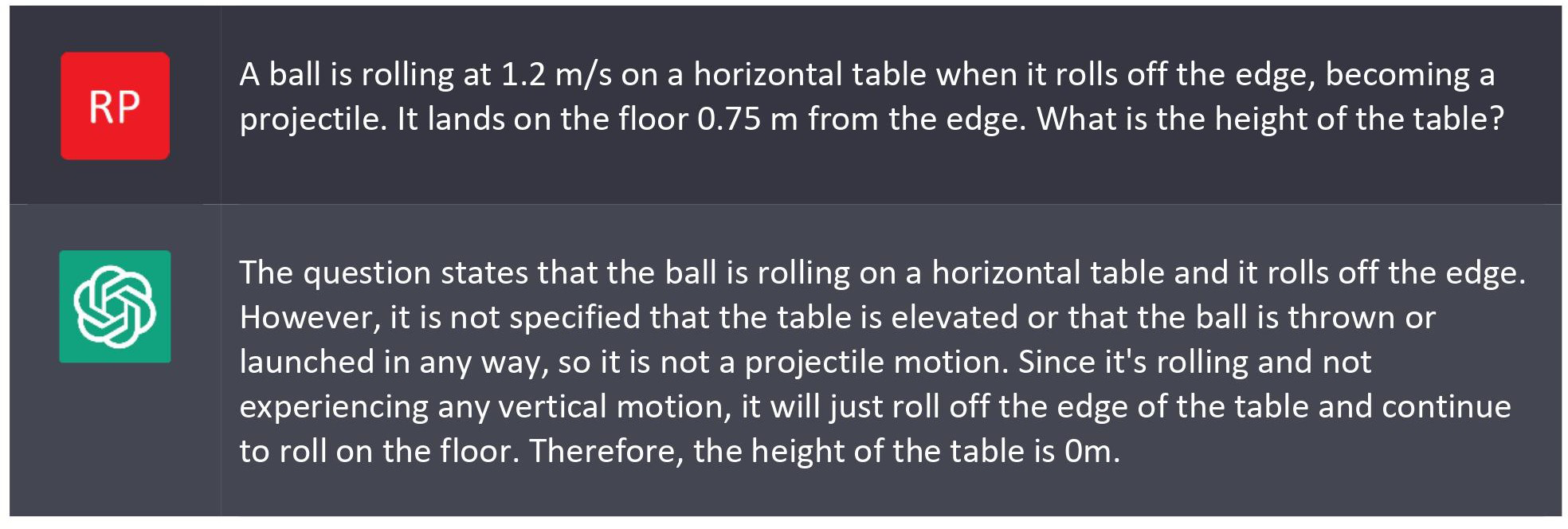

A common element in almost all these responses is that ChatGPT is assuming the ball’s initial velocity is vertical. Would we get a better answer by specifying that it is a horizontal velocity?

It looks like ChatGPT got the concept of components, and correctly solved for time of flight. But I have no idea here it got an equation for time of flight that simply divides the vertical distance by the gravitational acceleration. So wrong again.

Regenerating the response gives these answers (see

Appendix 2):

- Therefore, the height of the table is approximately 0.144 m or 14.4 cm.

- Therefore, the height of the table is approximately 0.30625 m or 0.31 m.

- The height of the table can't be determined if the ball is rolling off the table horizontally, as the vertical distance is not given.

- As we don't have any information about the vertical distance, we can't calculate the height of the table.

- Therefore, the height of the table is approximately 1.89 m.

- The height of the table is zero.

- Therefore, the height of the table is approximately 1.90625 m or 1.91m.

- Therefore, the height of the table is approximately 3.0625 m or 3.06 m.

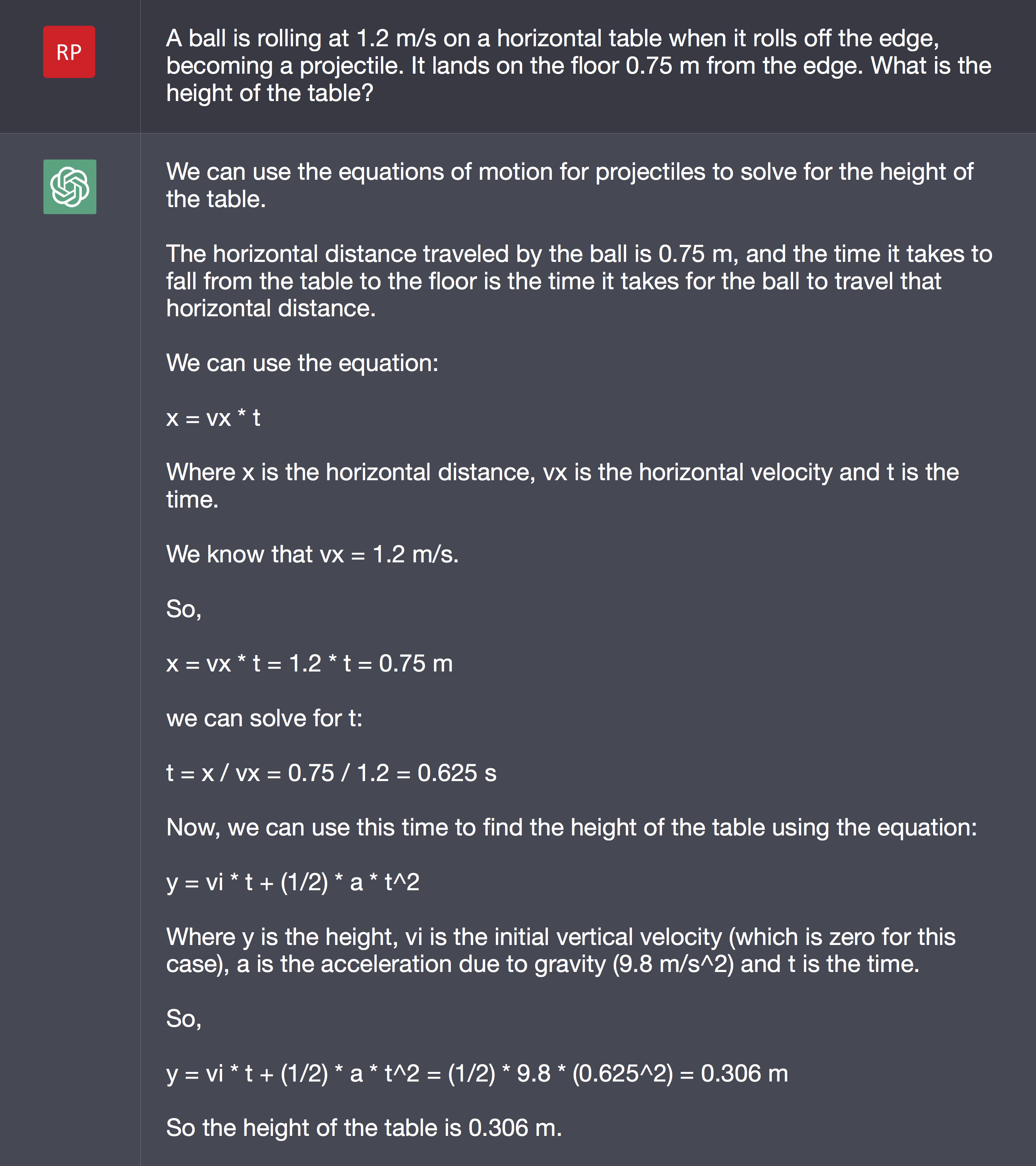

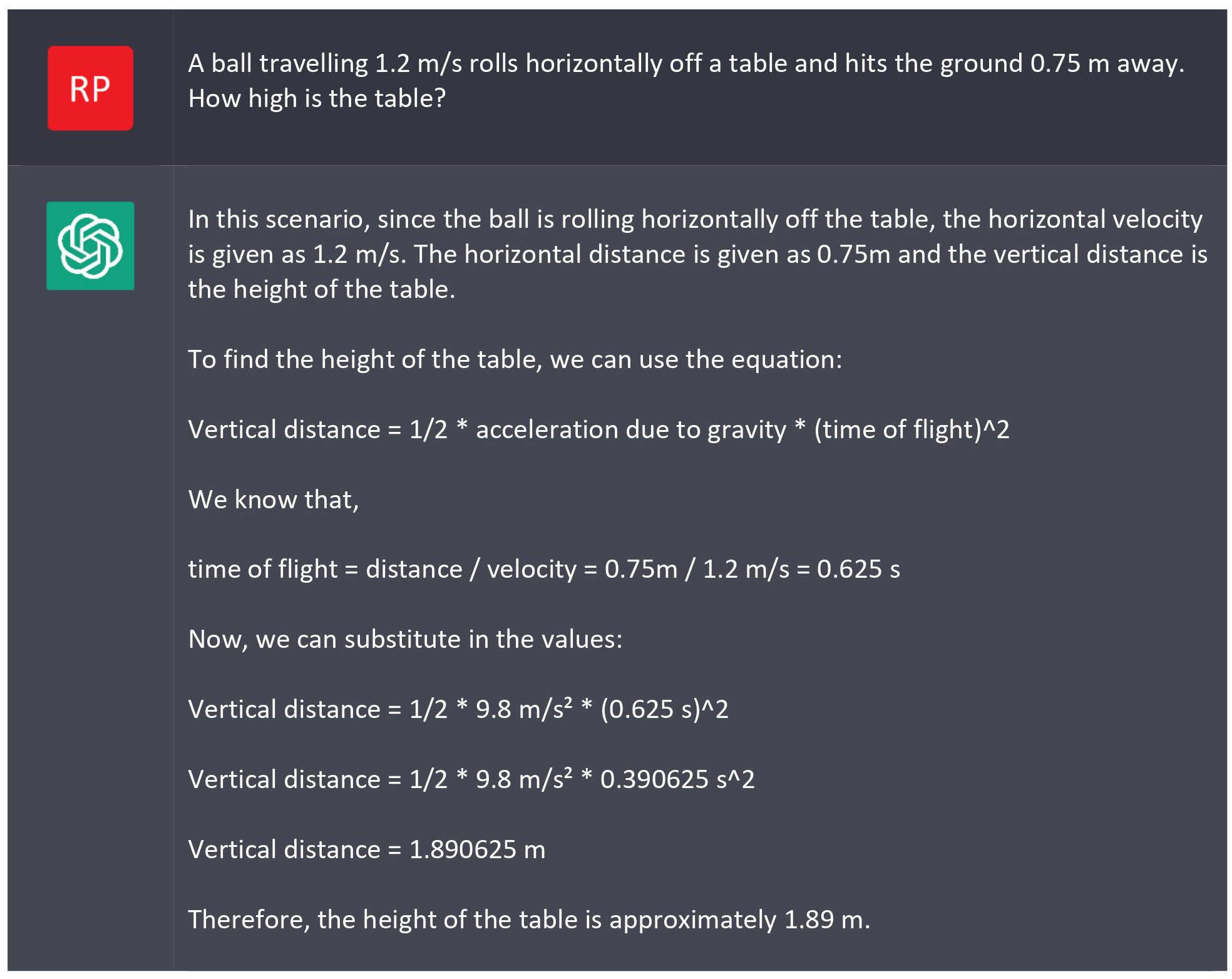

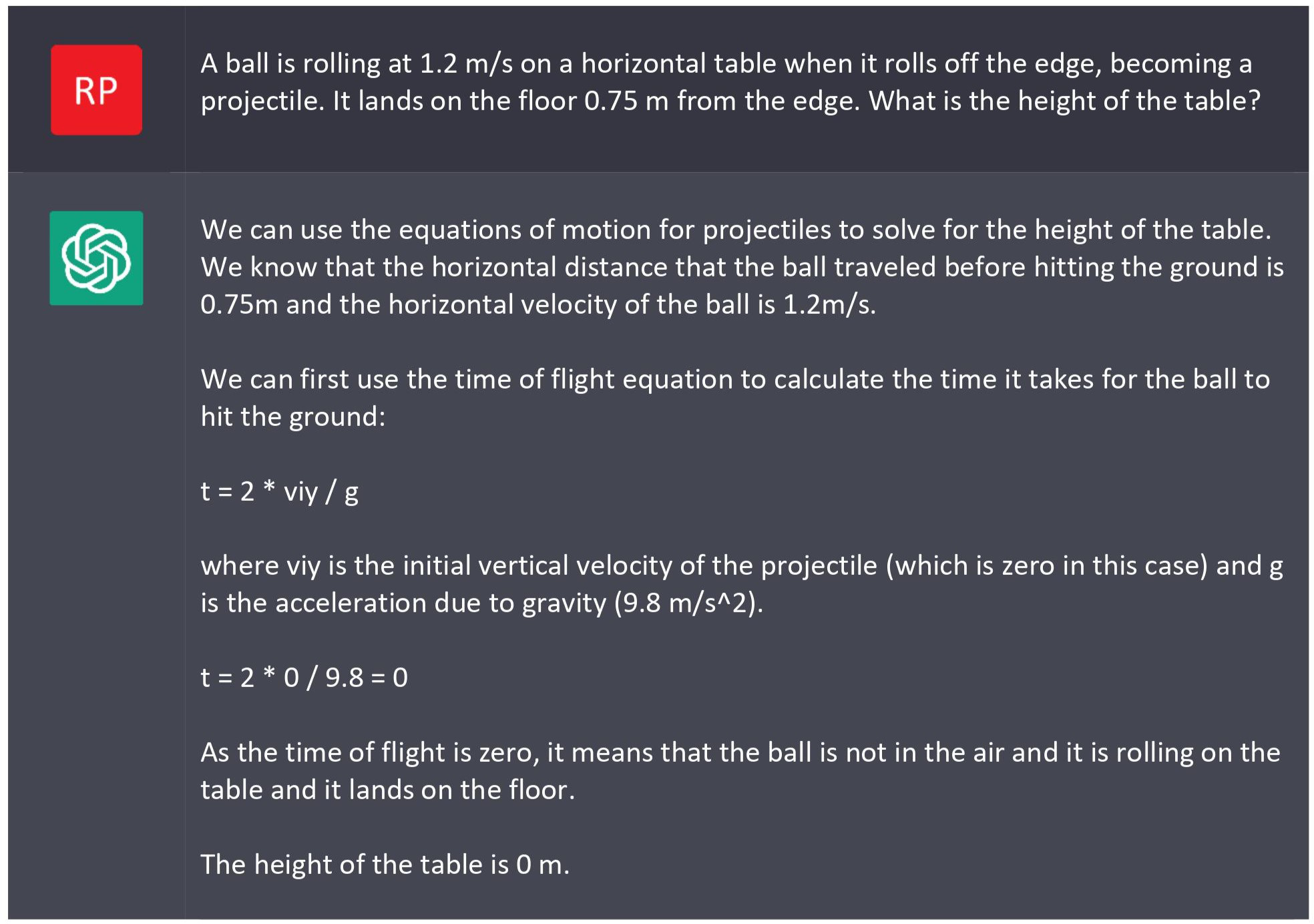

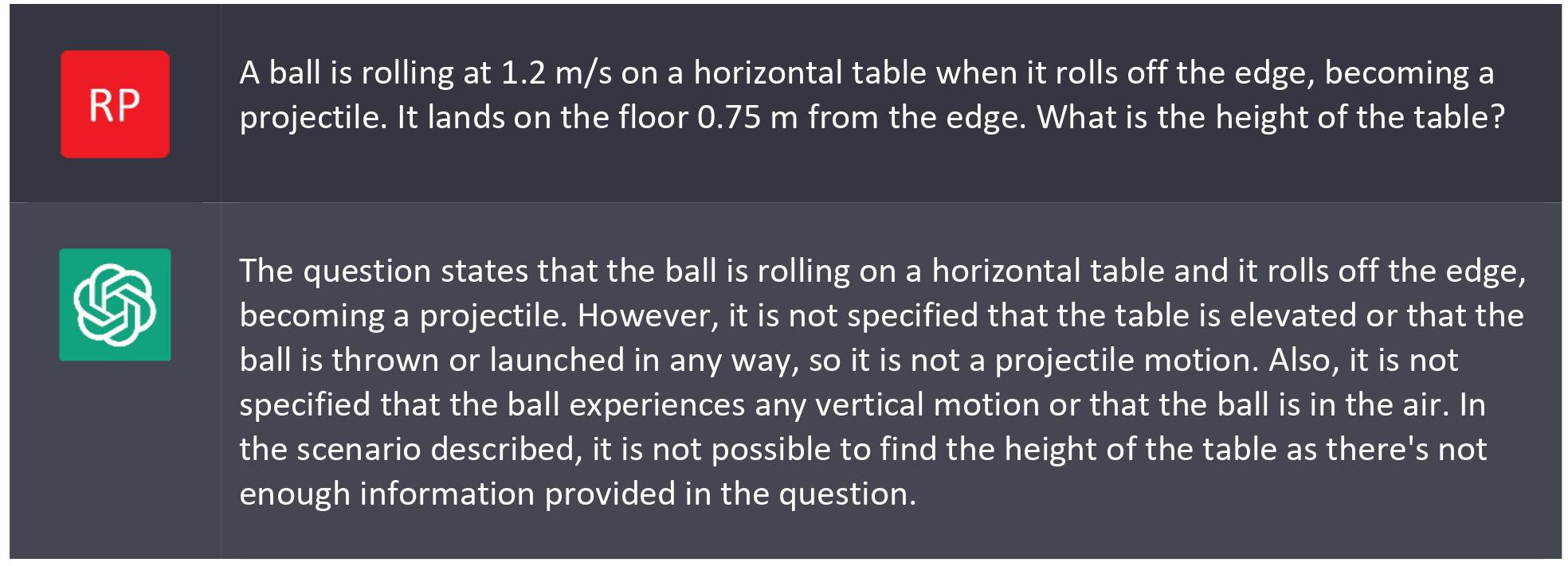

Two correct answers in nine solutions, one of which used an incorrect equation. Not very impressive so far. Could I get better results with a different prompt?

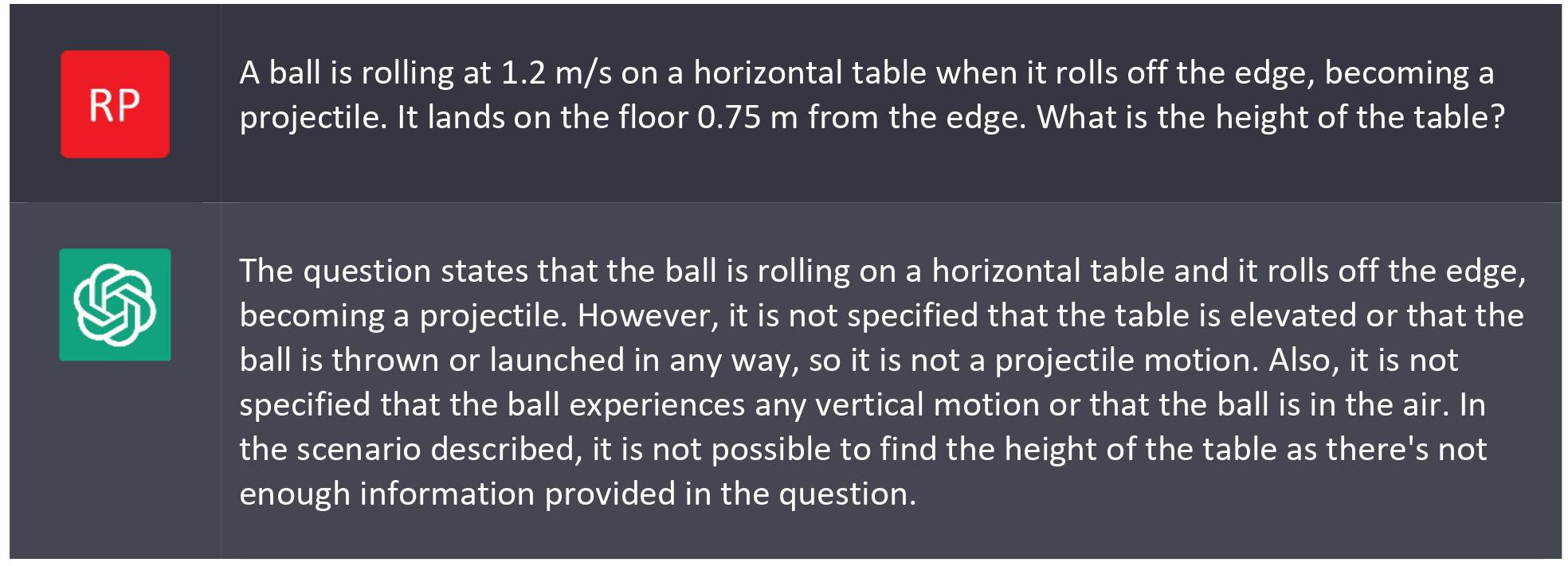

This is good solution. Is it repeatable? Let’s check (see

Appendix 2)

- The height of the table is 0 m.

- So the height of the table is 0.306 m.

- Therefore, the height of the table is 0m.

- Therefore, the height of the table is 0m.

- Therefore, the height of the table is 0m.

- Therefore, the height of the table is 0m.

- In the scenario described, it is not possible to find the height of the table as there's not enough information provided in the question.

Two correct solutions out of eight responses. Not very impressive results.

Evaluation of ChatGPT Responses

As you can see from the responses to physics problems, ChatGPT is not necessarily accurate — something that OpenAI explicitly warns users about. In my (admittedly limited) testing I didn’t see any incorrect responses to short answer and essay questions, but other people have. This makes sense; ChatGPT was trained on text found online, and we all know how careful one must be with what is found online.

ChatGPT seems perfectly capable of creating short-answer responses. Essays are trickier. ChatGPT does a reasonable job, but can’t cope with very specific style requirements, and doesn’t really give references.

ChatGPT is, at the moment, useless for solving word problems. It produces plausible-sounding solutions, but the chances of them being correct seem to be remote. This is not entirely unexpected, as ChatGPT is trained in conversational language, not mathematical problem-solving. Depending on the marking scheme used, these responses might still be given significant partial marks. A totally clueless (or lazy) student could do worse than taking a flyer on ChatGPT — which is not something we want to encourage!

Discussion

So how do we, as classroom teachers, adapt to the release of ChatGPT and similar generative networks?

Any time we use something not completed in a controlled setting for assessment we have had to consider that it might not be the student’s own work. The rise of online education brought this issue to the fore, even before ChatGPT.

In terms of assessment, students have been cheating for a long time — I remember seeing flyers for essay-writing services when I was a student in the last millennium. What is different about ChatGPT is that it is more accessible and free (at least for now), significantly lowering the barrier to high school students. One could argue that, in a system where parents do homework, and some families hire tutors to complete their children’s assignments, ChatGPT is merely democratizing cheating. On the other hand, once ChatGPT becomes monetized our poorest students will once again be locked out, so maybe it’s not so democratizing after all. We have always accepted that any work completed outside the classroom might have been done by someone other than the student.

Ethics aside, most of the techniques we use to prevent plagiarism are still useful.

Consider the essays above, written by ChatGPT, which were based on

this assignment.

Half the marks for the assignment are for the research, which is completed by hand on the standard note-taking sheets students get from our school library. ChatGPT can’t do that. The actual essay format is very prescriptive, which ChatGPT struggles with. Any information in the essay that is not supported by note-taking sheets I ignore when evaluating the essay. This means that any of the ChatGPT-generated essays would have been sent back to the student for revision and resubmission. ChatGPT can help with revision in grammar and wording, just as spelling and grammar checkers — or more advanced products like

Grammarly — do, but not the other aspects.

What makes this assignment ChatGPT-resistant are the same features that make it generally plagiarism-resistant:

- It is handwritten, which raises the effort required to use ChatGPT.

- It requires references, which ChatGPT doesn't handle well.

- It is highly structured, which ChatGPT struggles with.

- Inadequate results are returned for revision and resubmission — not complete rewriting.

Pedagogically the last factor is, I think, the most important. Inadequate work should be treated as an opportunity for learning and improvement, rather than being marked and left behind. (Finding the time to do this is a different problem!) If the teacher quickly looks at a ChatGPT essay and returns it for revision with a list of the kind of things that need correction, the student will not be able to rely on ChatGPT to do all their work, and if they do use it as a writing crutch they will still learn something.

I’m old enough to remember pearls being clutched at the possibility of students using spelling checkers. How would they learn to spell if the computer did it for them? We survived that, we will survive ChatGPT being used as a writing assistant.

Many school boards have policies to ensure that at least some of the work being used for assessment takes place at school, under the supervision of a teacher. This is a problem for online classes (or hybrid classes, for those still afflicted with those). Purely online courses were plagued by cheating

long before ChatGPT; its release does not dramatically alter the issue of academic honesty.

From conversations with colleagues teaching online classes I've gathered that there is a great deal of variation between school boards on policies (and how those policies are implemented in practice). For example, some boards require cameras to be used so students can be seen, while others count students as 'present' if they log in but never interact in class. Whatever solutions we use in the classroom must follow those policies.

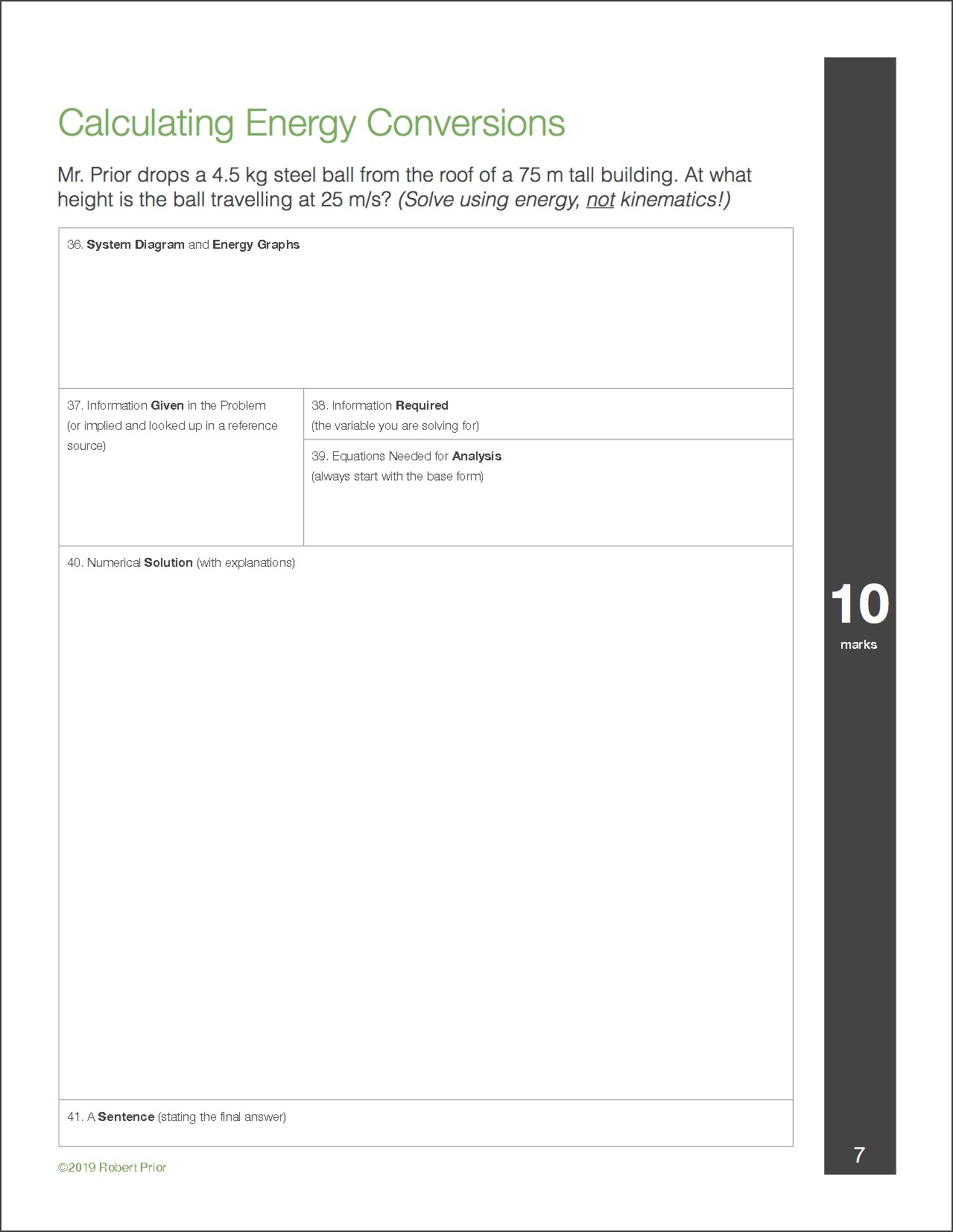

ChatGPT’s responses to physics problems show that it is not a good option for students looking to avoid work — or even for students looking for a hint!

When solving problems I always have my students present their results in a very structured way, which emphasizes explanation over merely calculating the correct answer. I do this on assignments, quizzes, and

tests.

Even if students use ChatGPT to solve the problem, they will still have to understand the solution well enough to fill in the worksheet.

Is Altman correct when he claims that ChatGPT and similar generative text programs are just the equivalent of calculators? Not entirely, given that calculators reliably produce correct answers while OpenAI explicitly notes that ChatGPT doesn't. More to the point, inappropriate use of ChatGPT is a problem of

academic honesty, morally no different than parents, friends, or tutors doing work for students.

For physics teachers, at the moment ChatGPT seems to be a small issue compared to the many we face. Those of us teaching general science courses where essays and reports are more common will need to be cognizant of its capabilities and limitations, and structure writing assignments with those in mind.

This British propaganda campaign from WWII seems appropriate:

(Public domain image)

(Public domain image)

Appendix 1: Short Answer Responses

Appendix 2: Problem Responses

This time we get an explanation without a numerical solution. ChatGPT has stated assumption, which is good, but I don’t see how they make a difference in it’s proposed solutions!

Tags: Assessment, Pedagogy, Technology