Eric Haller, Peel District School Board, Editor of the OAPT Newsletter

eric.haller@peelsb.com

The generative artificial intelligence ChatGPT was released upon the world back in November of 2022. This Newsletter published an article from Robert Prior on his

first impressions of it shortly thereafter in January of 2023. Now that our society is over the initial shock of AI, and more and more companies have had the chance to release and further develop their own competing chatbots (like Microsoft’s Copilot, Google’s Gemini, and China’s DeepSeek), I thought it would be a good time to revisit the topic. In this article, I will be looking at how generative AI has improved, and I will provide some thoughts on how it has impacted my students, myself as a teacher, and even some of my coworkers.

In the previously mentioned article on first impressions, we saw how ChatGPT performed when solving various physics problems. I thought the best physics question from that article was the following:

A ball travelling 1.2 m/s rolls off a table and hits the ground 0.75 m away. How high is the table?

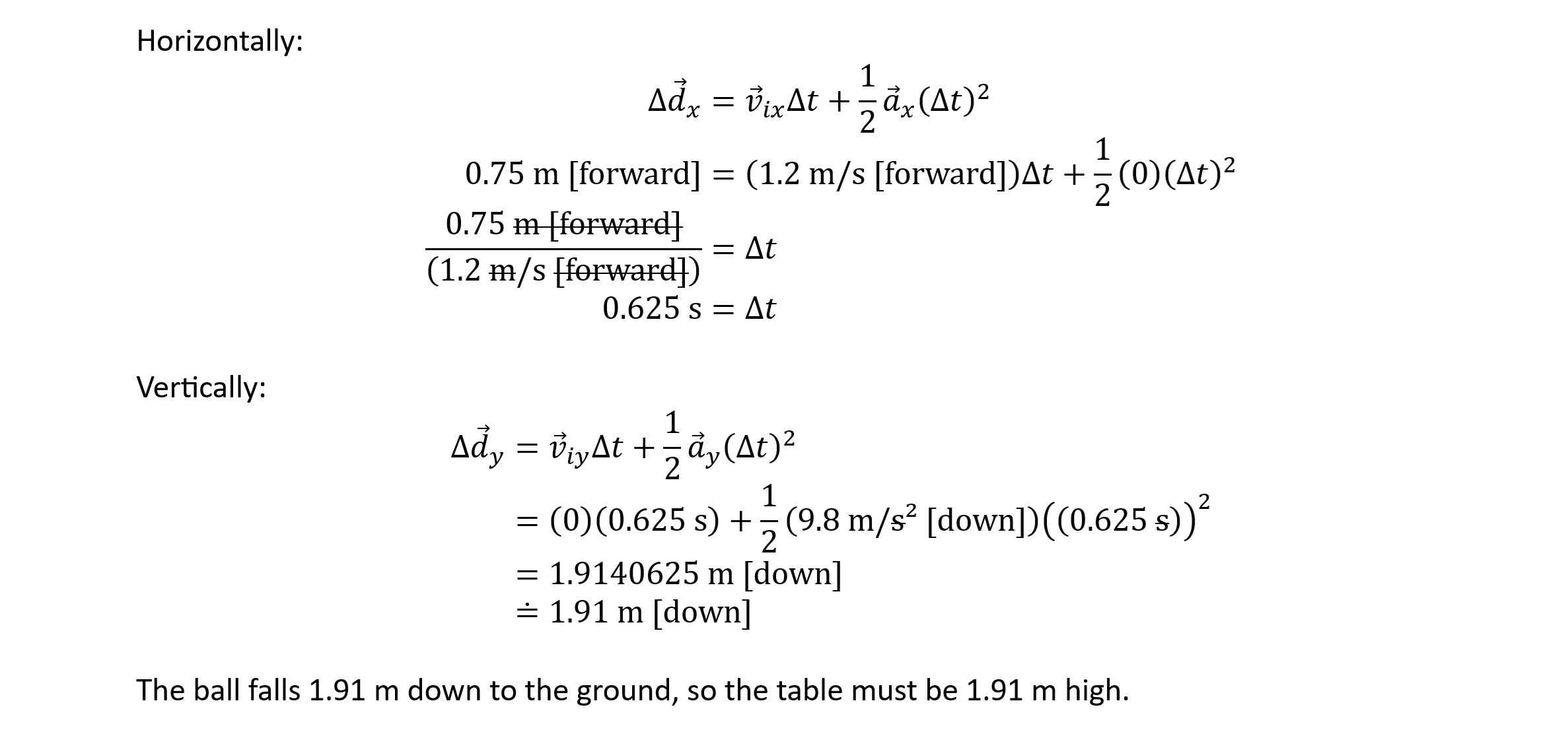

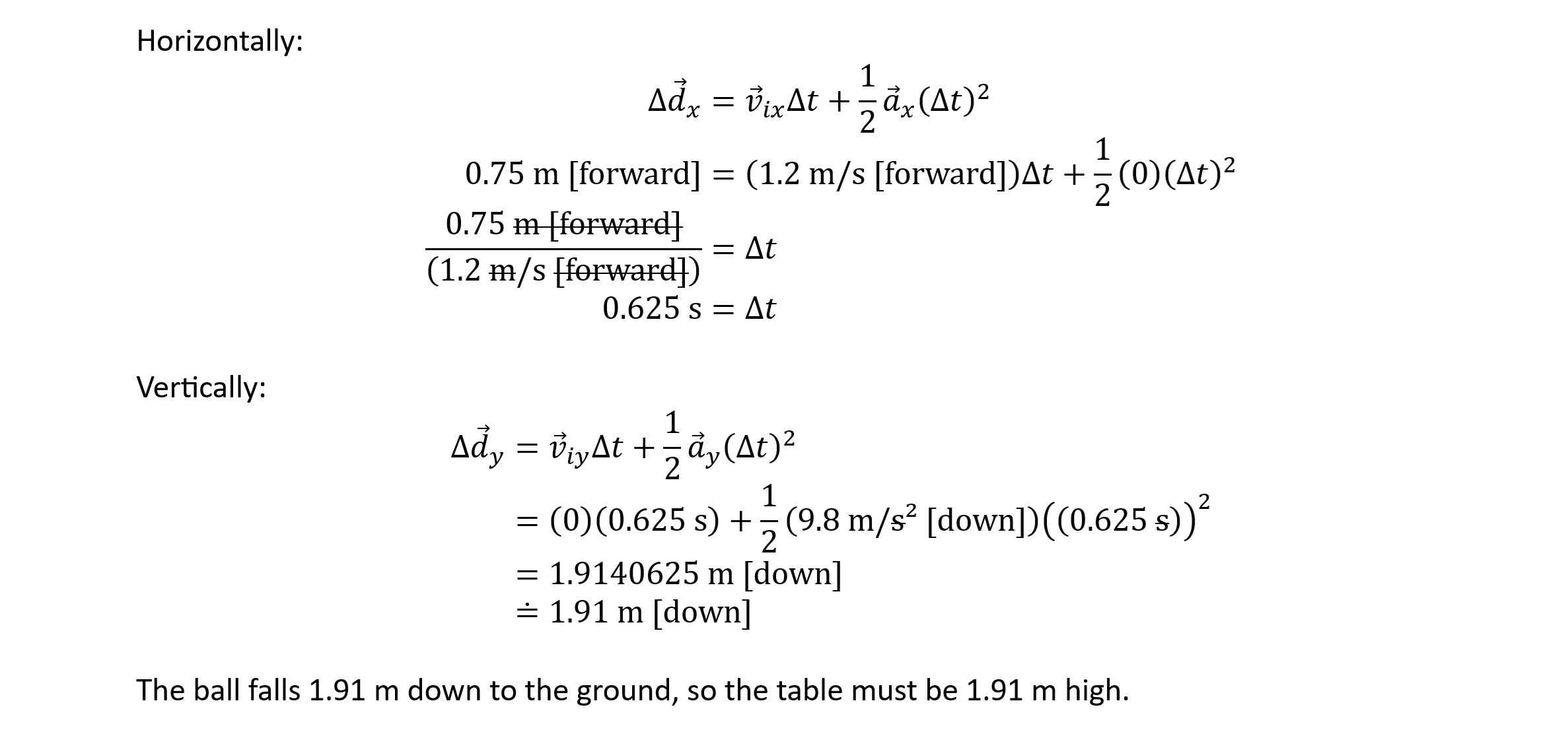

Before I pose this to today’s AI chatbots, here is my own solution to the problem:

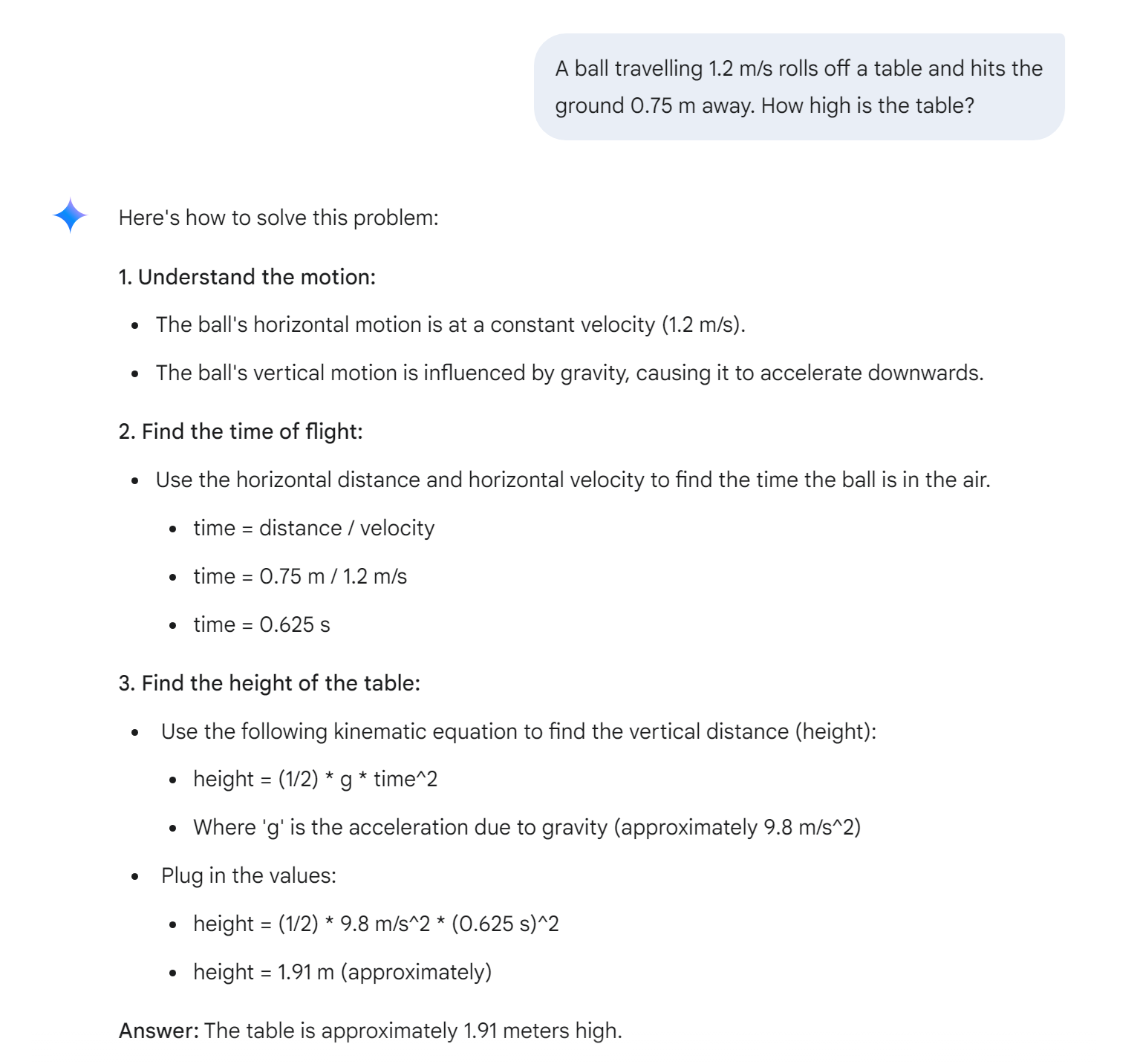

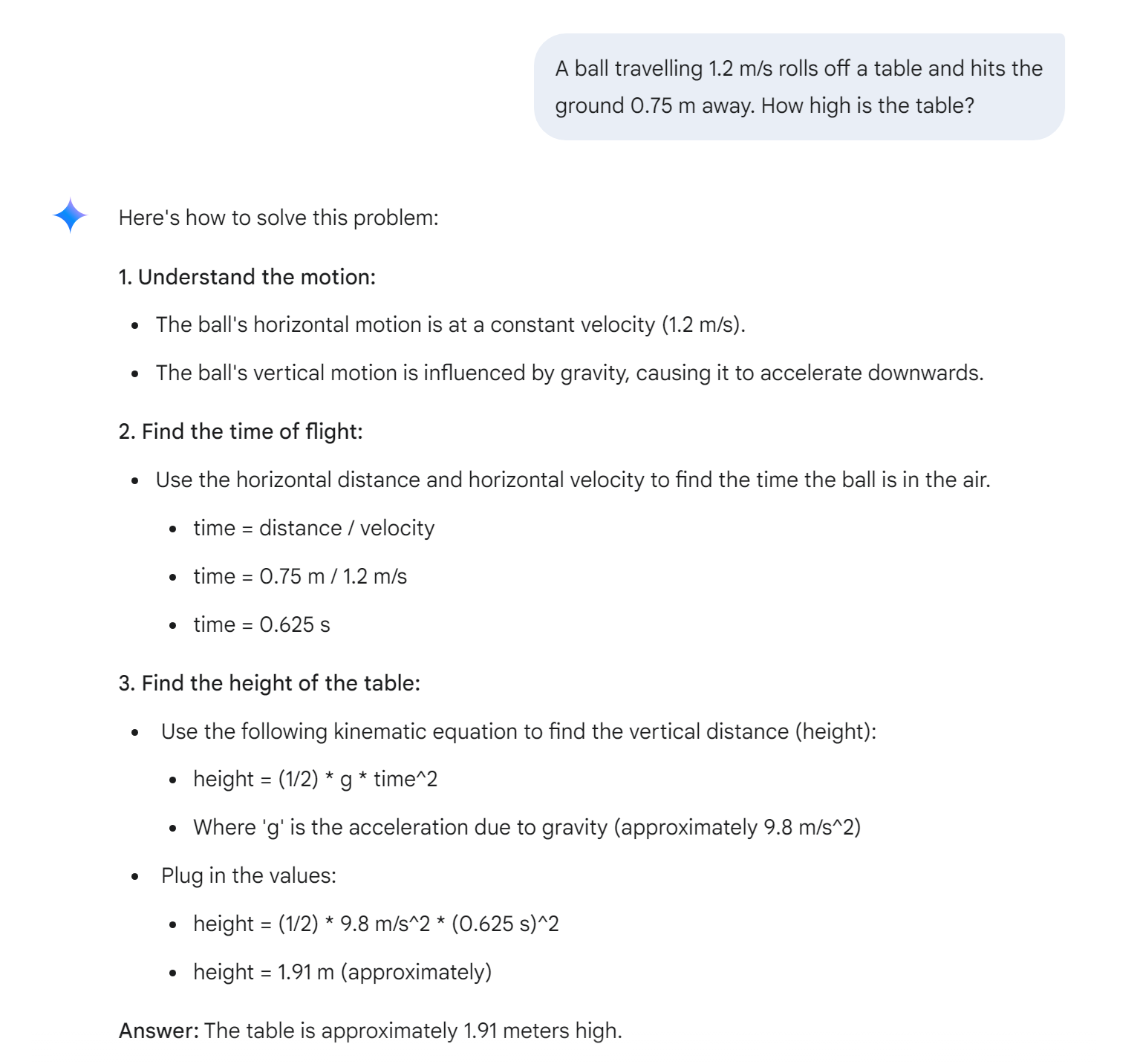

When ChatGPT was asked to solve this question back in January of 2023, the chatbot provided an explanation but no solution on the first attempt, and then incorrect answers of 0.153 m, 0.429 m, 0.624 m, 3.06 m, and 6.15 m on subsequent promptings. Running the exact same question through ChatGPT nowadays gave me an incomplete calculation again on the first attempt, but on the second prompt, it said this:

Now ChatGPT gets it correct! Furthermore, it managed to be correct without providing any incorrect answers beforehand. Next, I will try Google’s Gemini:

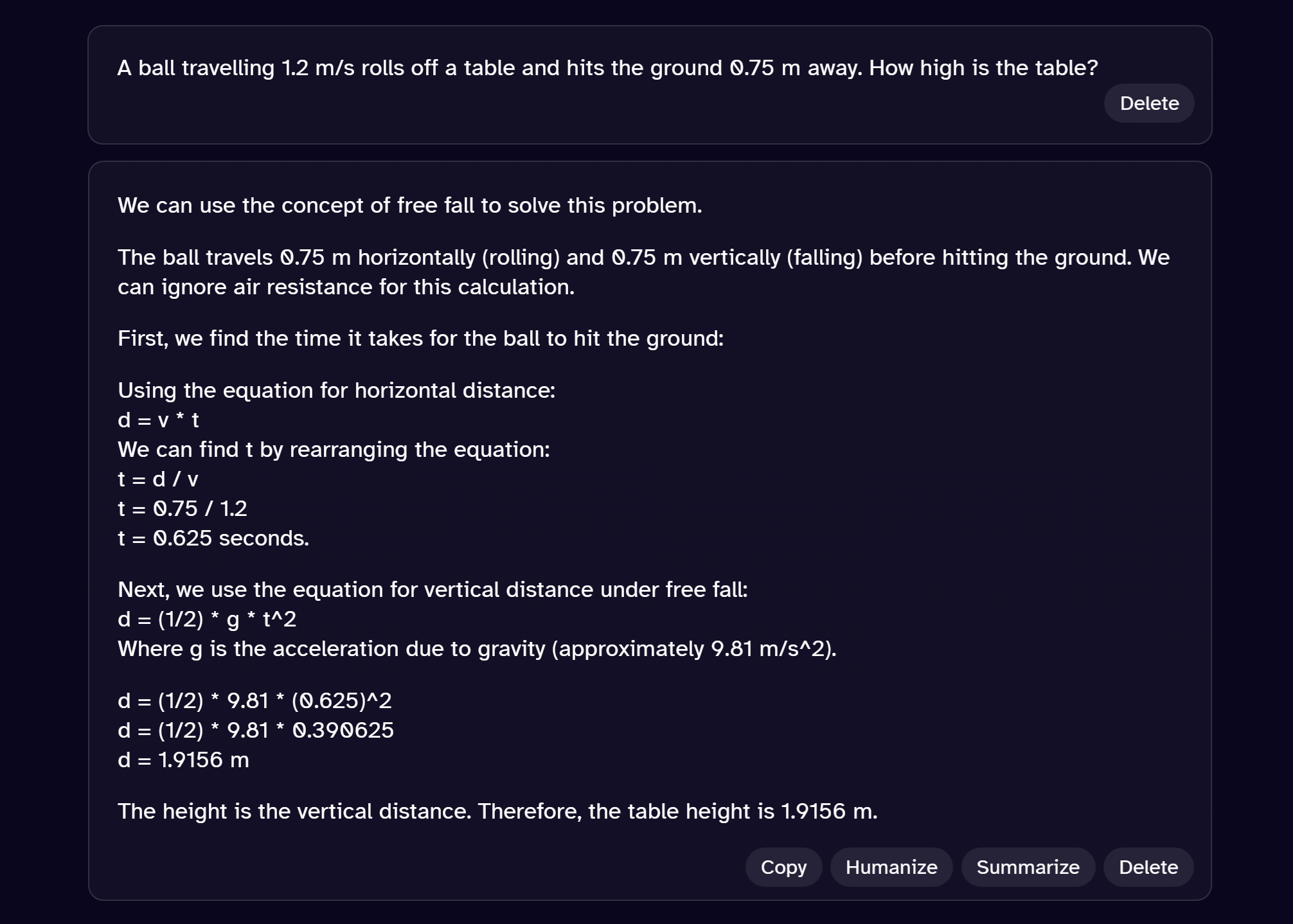

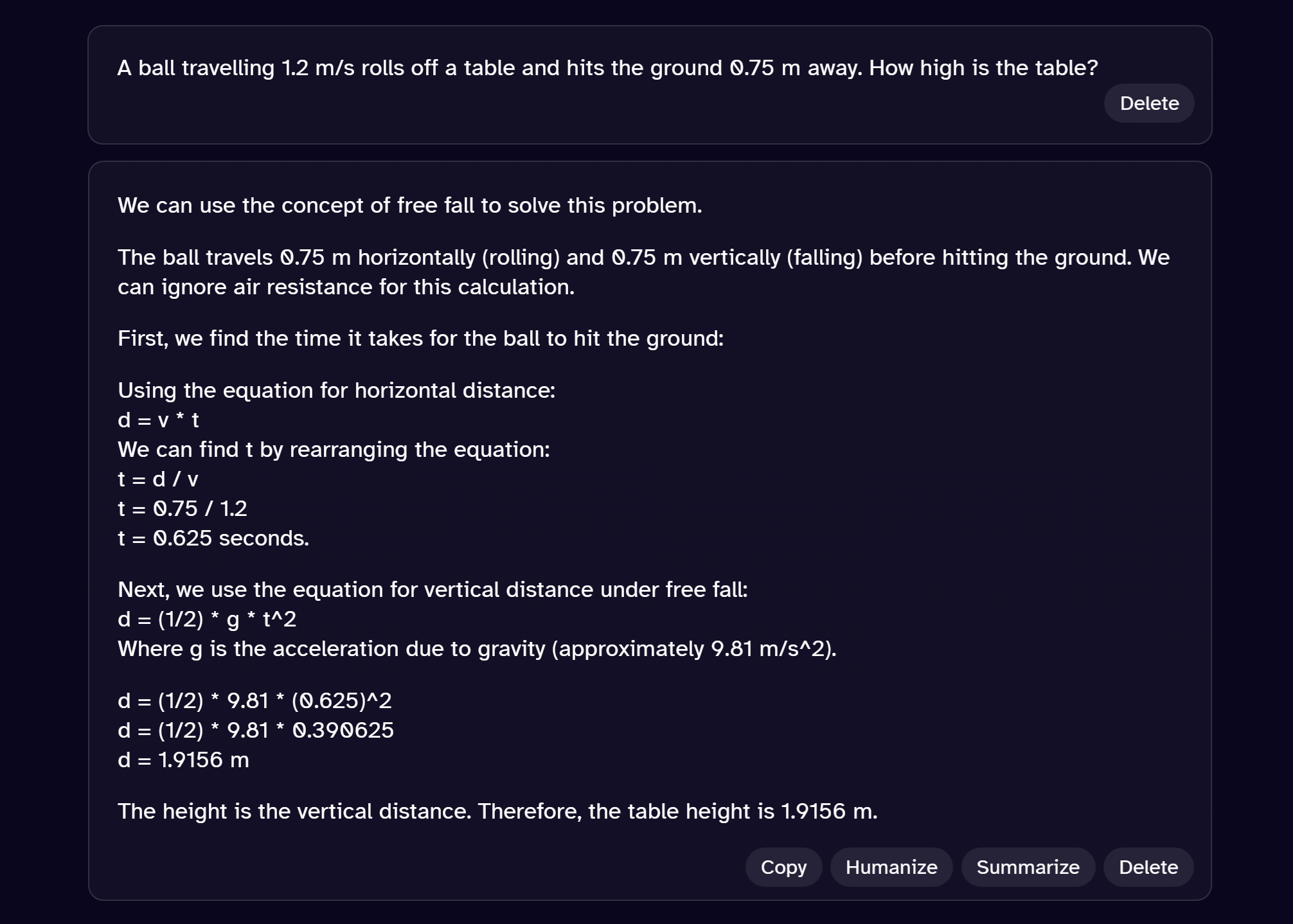

Gemini gets it right on its very first attempt! It even correctly rounds the answer to 1.91 instead of 1.92. Next, I will try a lesser-known AI; like DeepAI. On the first attempt it did not completely finish the calculation, but on the second attempt it solved the problem correctly:

As you can see, generative AI has made significant progress since it was released. ChatGPT went from six failed attempts, to being correct on the second attempt; with other chatbots also being able to perform on par, or better. I would have also tried running this problem through the

new Chinese AI which made waves in the stock market recently, however DeepSeek’s chatbot requires you to create a login. While the login is free, it is enough of a barrier to prevent myself — and likely most of my students — from actually using it.

So how does this affect physics teachers and students? For students, AI is a great tool to help them solve practice problems. AI chatbots may not be as accurate or valuable to students as a teacher or tutor, but they can be on par with working alongside a classmate (albeit a classmate who never sleeps, and who is happy to answer all of your questions immediately). AI can often give students the correct solution, and even when it makes a mistake (like classmates do), it still provides plenty of valuable insight. I even have a coworker who has created a custom chatbot using MagicSchool to help their students when their teacher is unavailable. I do caution teachers to be careful using AI in that type of a situation though, as chatbots cannot be held accountable for what they say, so that responsibility would instead fall on the teacher using it. I say that because of the recent

news story where Gemini told a user to “please die.”

While students can certainly benefit from using AI, there are some issues that arise. For one, if students run all the practice problems through AI to get the solutions right away, they miss out on most of the learning, which comes from actually solving the problems for themselves. An analogy I sometimes use is that when Olympic athletes prepare for their sports, they do so by practicing their sports. No Olympians ever got to the Olympics by simply watching and learning from other athletes competing on television. In addition to students missing out on actually practicing the practice problems, students who use AI too much also miss out on the sense of accomplishment they get after getting an answer correct after a dozen failed attempts.

More importantly, the real issues come from students using AI inappropriately, circumventing the entire learning process. Students using AI to help them complete the practice problems is not a major issue, but what about when they use it to complete a research assignment, a lab activity, a test, an exam, or even an interview? AI can do a pretty good job of most of the tasks I can create for my students, especially solving word problems and doing research. I teach online and recently had a virtual student arrive very late to an exam, with only about 15 minutes left to write it. Normally it would take students two or three hours to complete the exam, so I was amazed when this below-average student somehow completed my exam in that brief amount of time, and with time to spare! The student even got the majority of the answers correct (which I suppose calls into question whether or not I need to overhaul my virtual exams, or stop using them entirely). Given the circumstances, it was obvious the student had used AI, but it would have been hard to catch the student if they had shown up on time. To avoid detection, this student did not submit any rough work, just their final calculated results. This meant I could not run their work through an AI detector like ZeroGPT or QuillBot to catch it as being AI generated; and even when students copy and paste results straight from AI, the AI detectors are not reliable. The detectors are often right; but as a teacher, if I am only 90% sure a student used AI to cheat, I am not confident enough to call them out on it. There are also so many ways students can get around these detectors, like using Grammarly or QuillBot to ‘humanize’ text written by AI. Another way to avoid detection would be for the student to simply rephrase parts of the chatbot’s text. I have even seen students handwrite chatbot responses, making it harder for me to run it through an AI detector (using image to text extraction software is a hassle, and it really does not do a good job of equations). When I have confronted students about their misuse of AI, I have found they almost always lie about it, and they even double-down when pressed on it further. If I do a virtual one-on-one meeting with a student to address it, they could even use AI to help them during that meeting! You have likely seen videos floating around the internet showing job hunters using AI to help them answer questions during live job interviews. This allows the applicant to simply read off what the AI types out for them in response to what the interviewer asks.

With large classroom sizes, the frequency with which students are using AI inappropriately, the lack of consequences for students who get caught, and the time it takes to catch and then deal with those students, AI misuse has become a problem that is really hard and labour-intensive to combat. I find a lot of teachers simply give students the benefit of the doubt and grade AI generated submissions, instead of confronting the students. The level 1 and level 2 grades chatbots used to ‘earn’ for students was somewhat of an appropriate punishment, but now that these chatbots have gotten into the realm of level 3 and level 4 responses, that is no longer a significant deterrent to students. Rather than worrying about AI submissions on the back-end of an assessment, it is much less intensive to tackle it on the front-end by attempting to design assessments that are hard for chatbots to complete successfully. An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. Unfortunately, this prevents you from using many of the types of assessments that you have spent many years developing and fine-tuning over the course of your career; but I suppose teachers have always had to adapt and change with the times. Here are some methods that you may find useful to prevent students from using AI to complete your assessments (but note that as AI continues to develop, many of these tactics will eventually become obsolete):

- Talk about the appropriate and inappropriate uses of AI with your students at the beginning of the course. Put your expectations into your course outline. If you catch students using AI on assessments throughout the course, mention it to the whole class (without pointing fingers at anyone in particular) and use it as an opportunity to once again discuss the right and wrong ways to use AI.

- If you teach in-person, create assessments students can complete with pencil and paper (without using a computer or phone). The recent provincial cellphone ban helps with this. Design the assessments so they can be completed within one period, and do not allow students to take them home to finish them.

- Rather than focussing on written products, have students do interviews, presentations, debates, or a science fair. If you teach online, interviews can help, but note that students can use chatbots during interviews.

- Virtually, do not provide students with text they can easily copy and paste, like in a Word document or PDF file. Instead, provide the assessments in the form of an image or a video. This will help prevent students from simply copying and pasting the text into a chatbot, forcing them to actually type out the AI prompt for themselves. Note that students can extract text from images using an online image to text extractor, and it is not hard for students to get transcripts of what is stated in a video’s audio, but it is still a minor deterrent. Unfortunately, students who are English language learners will be at a disadvantage if they cannot select the text and have it pronounced out loud or translated for them.

- Rather than explaining a scenario in detail, use a picture or video to show what is happening. Limit the explanation of what is happening in the image/video as much as possible, as AI is not good at analyzing media. For example, instead of giving students the mass of an object in a problem, provide them with an image of the item on a balance scale, forcing them to look at a scale to read off the mass for themselves. You could also show a photo of a thermometer, forcing students to read the temperature off of it; or show an image of a car driving on concrete, implying (without actually stating) to students that they need to use the coefficient of friction between rubber and concrete. Graphs are another good way to present data in a way that is hard for AI to interpret. Students will often prompt AI to try to answer these kinds of questions, but if the AI is missing the context shown in an image, it is not likely to get the answer correct.

- Do labs (in real life or using a digital simulation) where students need to gather data. AI struggles to generate fake data results, like if you ask it to drop a ball from various heights and measure how long it takes the ball to hit the ground. Note that AI is pretty good at telling students what kinds of values they should expect to get (with equations), allowing students to then make up appropriate data for themselves without actually doing the experiment. AI may even provide students with a template of the table they could use to put their data in.

- Ask students to submit drawings or images. AI is not very good at doing free body diagrams, or creating infographics. That said, there are plenty of AIs out there that can draw pictures, like Midjourney and DALL·E 3.

- Have students complete hands-on activities, or have them build things like a can crusher, trebuchet, or Rube Goldberg machine. In-person, have them present their creation; or virtually, have them make a video presenting what they created. If students ask if they can submit a written report without a presentation or video, consider telling them “no”, or build your rubric in such a way that students who do not submit a video or do a presentation would lose a lot of marks.

- In your assessments, tell students they are not allowed to include research beyond the lessons you taught in class, limiting their knowledge to what you taught them during your lessons. AI does not know what you did or did not teach, so it will sometimes use equations or principles that your students should not be aware of. If a student uses the horizontal range equation to solve a projectile motion problem, but you never showed the student that equation, then that would be a good indicator the student got their solution from a chatbot, or perhaps a Google search. By building this principle into my rubrics, it gives me a way to deduct marks from students who use AI, without me having to even accuse them of using AI!

- Break your large assessments down into smaller portions, with check-ins scheduled here and there. AI does not tend to do rough and incomplete work, and it struggles to iterate on what it has already done in the past. AI is much better at just providing a final, completed result.

If, after designing your assessments to be somewhat AI resilient, you still think some students are using AI to complete their assessments, here are some tips on how to detect that. Note that these techniques are mostly subjective and have their flaws, and many of them will become obsolete over time:

- If the student says something that only an AI would say, they probably used AI! For example, I asked ChatGPT to drop a ball from different heights and record the length of time it took for the ball to hit the ground from each height. ChatGPT replied with “While I can't perform real-time calculations or physical experiments at the moment, I can still guide you through how to calculate the time it takes for a ball to fall from different heights using the principles of physics”. This is a clear indication that the student used AI to answer the problem without ever reading the response to check if it made sense. This reminds me of when students would ‘do’ the homework, but then write out the answer to a question as “answers may vary” after looking at the answers in the back of the book.

- If a student discusses things that are above and beyond what you taught them, then it may be written by an AI.

- If students who are learning English submit tasks written in fluent English, it may be AI generated. Software like Adobe AI can even take a video of a student speaking one language and effortlessly dub it into another language; cloning the voice to match that of the original speaker, and adjusting the original lip movements to match the new words (English language learners translating their spoken audio in their mother tongue to English isn’t so bad in a physics class, however in an English or French class that might be more of an issue).

- If a particular submission is much worse or much better than what a student normally submits, and if it sounds off (not their typical tone or level of vocabulary), it may have been generated by a chatbot.

- If you are doing online assessments and have access to time logs, use them. If you find a student somehow typed out a full page of work in a minute or two, that is a good indicator they did not actually type it out themselves.

- If the student breaks down their solution into a bunch of steps and over-explains each step, it might be the work of a chatbot. For an example of what I mean, compare my solution to the problem posed at the beginning of this article to the solutions by AI. My equations are short and sweet, but the AI solutions use more words than math. Especially keep an eye out for “Step 1”, “Step 2”, and so on, as AI loves to explicitly state it is using a sequence of steps.

- AI generated work will often miss out on particular elements of an assignment you requested, like not including a free body diagram. AI does not do a great job adhering to a rubric, especially when students never share the rubric with the chatbot.

- Use AI detectors like ZeroGPT or QuillBot to scan over students’ work. If students handwrite their work to avoid AI detection, you can use online image to text extractors to get around that. Note that some students will ‘humanize’ their AI generated content using things like Grammarly or QuillBot to avoid detection, and note that AI detectors are not that reliable. They often provide false negatives; and even worse, false positives.

- When asking students questions about their submission, their inability to answer your follow up questions is a good indicator they may not have played much part in creating the original submission.

All in all, the advent of generative AI has had a huge impact on students and teachers in the short time it has been around, and with AI progressing as fast as it has been, the impacts will only continue to grow in the coming years. I have heard one teacher tell me their school has abandoned online assessments altogether because of how easy it is for students to use AI to complete them. I work at a virtual school, and while a few years ago during COVID I thought online education might eventually become the golden standard at some point in the future, the advent of AI has quickly changed my opinion of that, giving the edge back to brick-and-mortar schools where it is much easier to combat AI misuse. I wish you all the best of luck in navigating the current AI landscape, and what is to come.

Tags: Assessment, History, Pedagogy, Remote Learning